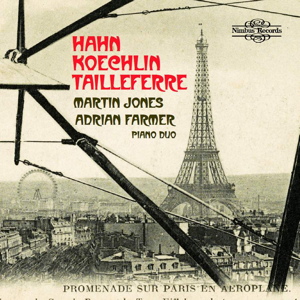

French Music for Two Pianos

Martin Jones, Adrian Farmer (pianos)

rec. 2019/2022, Wyastone Leys, UK

Nimbus Records NI5953 [2 CDs: 151]

Reynaldo Hahn, Charles Koechlin, and Germaine Tailleferre make for entertaining company on this newest release by the Jones/Farmer piano duo. The recording could have been titled “The Ghost of Emmanuel Chabrier”; his shadow looms large over the scores, particularly those of Hahn and Tailleferre. Francis Poulenc referred to Chabrier as “mon grand-père,” and given the audible influence of the older composer on the sparklingly clear textures and piquant harmonies heard here, one assumes that Hahn and Tailleferre were also part of the same family.

Hahn certainly shared Chabrier’s penchant for waltzes; the large suite Le ruban dénoué (“the ribbon untied”) is a collection of twelve waltzes with evocative titles, written towards the end of the Great War. The excellent booklet note by Dr. David Jones draws the reader’s attention to a painting of the same name by American painter Paul Cadmus. If one is at all familiar with Cadmus (best-known in the United States for his boundary-pushing 1934 tempera painting “The Fleet’s In”), it will come as no surprise that his version of Le ruban dénoué features the composer Hahn being kissed by a floating Cupid as the triumphant god Pan celebrates from several feet away. Cadmus’s untied ribbon is an enormous piece of lush red and blue fabric that frames the figures as well as the mostly eclipsed moon, which is perhaps a nod to Hahn’s famous mélodie “L’heure exquise.” After seeing the painting, the music is almost a let-down, being much more subtly sensual than the image would suggest. Most of the waltzes are of the gently rippling variety, but Hahn’s approach to harmony and rhythm is varied enough to sustain interest throughout the thirty-five-minute set. In the first of the waltzes, titled “Décrets indolents du hasard,” Hahn toys with the rhythmic concept of duple v. triple, alternating the two patterns bar by bar. Another waltz has quintuplets vying against triplets. These sorts of rhythmic games can be heard throughout the suite. All of the works feature an odd hallmark of Hahn’s compositional style: the avoidance of the use of the low bass on the piano. The composer tends to keep his piano textures towards the middle of the instrument, with occasional flights above the staff. The result is a soundworld that is delicate, lacking the Romantic heft found in the scores of his contemporary songwriter Henri Duparc. These are fascinating pieces that should be listened and re-listened to in small doses for full appreciation.

Koechlin is the least interesting of the three composers, his music possessing more of an academic flavor than that of his student Tailleferre or his contemporary Hahn. Although Dr. Jones makes a spirited defense of Koechlin’s propensity for canons and other forms of counterpoint (“[they] are always a means to an artistic end, rather than a mere intellectual exercise…”), the essentially placid nature of the music defeats the dramatic tension inherent in good contrapuntal writing. (Saint-Saëns is an example of a French composer who understood how to whip up a real climax using counterpoint. The concluding fugue of the Caprice on themes from Alceste is an electrifying crowd pleaser.) The Koechlin scores included here meander pleasantly along, with the occasional allegro final movement interrupting a steady stream of andantinos, moderatos, and allegrettos, none of which are so strongly characterized as to stand out significantly from one another.

The works of Tailleferre provide more interest; she studied with Koechlin and may have acquired a command of polyphony at his knee, but she wears her knowledge lightly. The slow movement of the Sonata skillfully weaves together several lines and has a modal essence similar to many of the Koechlin pieces, but the music lives in a deeper emotional world. This short two-piano Sonata, originally written for the Gold & Fizdale duo, is a real highlight of the album.

The performances are good. Jones and Farmer play this delightful music with much humor and obvious enjoyment. My only quibble comes down to tempi; the fast movements tend to be slowish and the slow movements fastish, resulting in a feeling of sameness to some of the multimovement pieces. After appreciating the Jones/Farmer rendition of the Tailleferre Sonata, I listened to a performance by Marc Clinton and Nicole Carboni, and found the latter duo’s performance more engaging due to a sharper delineation between Allegretto, Allegro, and Andantino, as well as more incisive articulation. Overall, however, this is an affectionate overview of these scores gathered in a single convenient location, and as such, is an invaluable addition to the libraries of fin de siècle fanciers. I look forward to hearing more French two piano music from the Jones/Farmer duo.

Richard Masters

Previous review: William Kreindler (August 2023)

Contents

Reynaldo Hahn (1874-1947)

Caprice mélancolique, for 2 pianos [5:01]

Le ruban dénoué, 12 waltzes for 2 pianos [38:07]

Pour bercer un convalescent, for 2 pianos [4:58]

Charles Koechlin (1867-1950)

Suite for two pianos, Op. 6 [11:34]

Suite for piano duet, Op. 19 [14:41]

Sonatines Françaises pour piano à 4 mains, Op. 60

Sonatine No. 1 [7:36]

Sonatine No. 2 [10:33]

Sonatine No. 3 [5:38]

Sonatine No. 4 [6:49]

Germaine Tailleferre (1892-1983)

Jeux de plein air (Outdoor Games) [5:37]

Image [4:28]

Fandango [3:24]

Deux Valses pour deux pianos [3:34]

Intermezzo [3:46]

Toccata [3:33]

Sonate pour deux pianos [7:30]

Choral et variations [11:15]