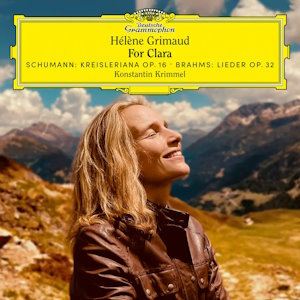

For Clara

Robert Schumann (1810-1856)

Kreisleriana, Op 16 (1838)

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897)

Intermezzi, Op 117 (1892)

Lieder und Gesänge, Op 32 (1864)

Hélène Grimaud (piano)

Konstantin Krimmel (baritone)

rec. 2022, Biblioteksaal, Kloster Polling (Schumann); Turbinenhalle am Steinitzsee, Berlin (Brahms Op 32); 2023, Tonstudio Tessma, Hannover (Brahms Op 117)

German texts & English translations included

Deutsche Grammophon 486 4202 [73]

This intelligently devised programme consists of music by Robert Schumann and Brahms but, as the album’s title suggests, Clara Schumann is a huge background presence. Robert Schumann composed Kreisleriana before his marriage to Clara Wieck but, as Kenneth Chalmers points out in his notes, Robert proposed dedicating the score to Clara, though in the end that honour went to Chopin. I’m not aware of an explicit connection between Clara and Brahms’ Lieder und Gesänge but, of course, the two of them were very close for decades. The notes remind us that he sent her a copy of the Op 117 Intermezzi (and of the Op 116 Fantasies) soon after the pieces were completed.

Hélène Grimaud gives a fine account of Kreisleriana. She makes an immediate positive impression by conveying very well the surging energy of the opening piece, which is marked Außerst bewegt. Whenever Schumann calls for lively playing, Grimaud delivers the goods, as for instance in the seventh piece (Sehr rasch) where she demonstrates great drive. But she impressed me most of all in her delivery of the more reflective pieces. The second piece (Sehr innig und nicht zu rasch) is, by some distance, the longest of the eight. It’s true that there are a couple of quick episodes, where the playing has suitable urgency; however, for the most part Grimaud plays this piece with lyrical freedom, which is just what the music needs. Again, in the thoughtful sixth piece (Sehr langsam) she evidences a lovely, poetic touch. The last piece (Schnell und spielend) has a lot of dexterous, playful content, to which Grimaud responds in an ideal fashion. This is a most enjoyable performance of these character studies.

I enjoyed Hélène Grimaud’s reading of the three autumnal Intermezzi which Brahms composed just a few years before he died. I like the poetic freedom she brings to the first one, in E flat; her use of rubato is very sensitive. The second Intermezzo, in B flat minor, is introspective and serious; Grimaud seems entirely as one with the music. She’s just as well attuned to the third piece, in C sharp minor. These pieces, full of melancholy and intimate communication, are choice examples of late Brahms and Hélène Grimaud does them very well.

For the set of nine Lieder und Gesänge Hélène Grimaud is joined by the German-Romanian baritone Konstantin Krimmel. This isn’t the first time they’ve appeared on disc together. Not long ago, DG issued their recording of a selection of Valentin Silvestrov’s Silent Songs. In his review, my colleague Roy Westbrook related that Hélène Grimaud had discovered Silvestrov’s songs almost twenty years previously. She then began a long search for the ideal voice to partner her in Silent Songs; that search eventually led her to Krimmel. I see that the recordings of both the Silvestrov and Brahms songs took place in the same month and in the same venue, Turbinenhalle am Steinitzsee, Berlin. In the DG booklet for the Silvestrov we’re told that those songs were recorded live on 31 August 2022, but there’s nothing to suggest that the Brahms songs were also recorded live.

In these songs Brahms set poems by two German orientalist poems, Georg Friedrich Daumer (1800-1875) and August von Platen (1796-1835); Daumer’s poetry furnished five of the texts that Brahms set and von Platen’s work was mined for the other four texts.

The partnership between Grimaud and Krimmel is strong and effective. Furthermore, because the piano parts are substantial, these songs require it to be a partnership of equals, which it is. Grimaud is just as impressive here as she was in the solo items and she combines extremely well with her singer. Krimmel possesses a fine voice which is well suited to those songs. In the very first song, ‘Wie rafft’ ich mich auf in der Nacht’ he inspires confidence through his well-placed, forward voice. Both tone and diction are clear and the voice is steadily, evenly produced. He’s eloquent in the second song, ‘Nicht mehr zu dir zu gehen’, capturing well the sense of longing in both the words and the music. The fourth and fifth songs, ‘Der Strom, der Neben mir verauschte’ and ‘Wehe, so willst du mich wieder’ are impassioned pieces and these artists rise to the occasion splendidly. By contrast, both singer and pianist offer a rapt performance of the final song, ‘Wie bist du, meine Königin’. This is a very fine account of Brahms’ Op 32 songs. Grimaud and Krimmel seem to get everything just right and they are alive to all the nuances in the set. They have combined to excellent effect, both here and in their Silvestrov recital; I hope they will continue their fruitful partnership on disc.

This is a thoughtfully conceived and excellently executed programme. In particular, I applaud Hélène Grimaud’s decision not to present simply a recital of solo piano works but, instead, to think outside the box and combines Lieder with piano works. Though the sessions took place at three different locations and on three separate occasions, DG’s engineers have produced nicely consistent and excellent sound. Kenneth Chalmers’ notes are valuable.

Help us financially by purchasing from