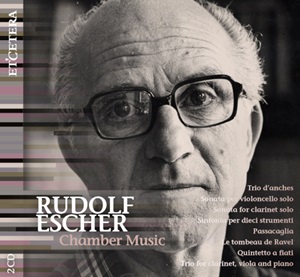

Rudolf Escher (1912-1980)

Trio d’anches (1939, rev. 1941/1942)

Sonata per violoncello solo (1948)

Sonata for clarinet solo (1973)

Sinfonia per dieci strumenti (1973/1975)

Passacaglia for organ (1937, rev. 1946)

Le Tombeau de Ravel (1952, rev. 1959)

Quintetto a fiati (1966/1967)

Trio for clarinet, viola and piano (1979)

Dirk Luijmes (organ), Gruppo Montebello/Henk Guittart

rec. 2021, Abbey Church Rolduc, Kerkrade (Passacaglia), Library of the Monastery, Wittem (Trio d’anches), Aula Minor Rolduc, Kerkrade (Sonata for clarinet solo), Sint Janskerk, Maastricht (Sinfonia), 2022, Parkstad Limburg Theater, Kerkrade (all other works), The Netherlands

Et’cetera KTC 1789 [2 CDs: 154]

Rudolf Escher may be the most important Dutch composer of the second half of the 20th century, but he is little known outside the Netherlands. With apologies for the lengthy introduction, let me offer a brief bio. He was born in Amsterdam but spent his childhood in Batavia (Jakarta now), where his father was a geologist with an oil company. Back in the Netherlands in 1922, he started musical studies but was undecided about his artistic career: he was drawn to painting and writing too. He then decided to enter the recently founded Conservatory in Rotterdam, where in 1934-1937 he studied composition with Willem Pijper (1894-1947), a highly regarded figure on the local and international musical scene.

Most of Escher’s early compositions were destroyed during the bombing of Rotterdam in May 1940. He continued composing during the war, and eventually made his mark as a significant composer when his marvellous orchestral work Musique pour l’Espriten Deuil (1942/1943) received its first performance by the Concertgebouw Orkest conducted by Eduard van Beinum. From then on, he composed prolifically, mainly chamber works and vocal music. Over forty years, he composed several large-scale works, including two symphonies, one in 1953/1954 and one in 1958, revised in 1964 and 1971. Next, we have the wonderful HymneduGrandMeaulnes(1951/1952), possibly his greatest orchestral achievement, and two vocal works on French texts for tenor and orchestra: Nostalgies (1951, revised 1961) and Univers de Rimbaud (1970). And let us not forget the substantial Concerto for String Orchestra (1947/1948). He also composed choral works on a large variety of texts, among them Songs of Love and Eternity (1955) on poems of Emily Dickinson, Le vrai visage de la paix(1953, revised 1957) on texts of Paul Eluard, Ciel, air et vents (1957) on poems of Pierre de Ronsard and Three Poems by W. H. Auden (1975).

Over the years, Escher never ceased to explore new techniques, including serialism, to which he never adhered unconditionally. He also composed an electronic score for The Last Christmas Dinner (1960), and Summer Rites at Noon (1962/1969), a piece for two orchestras facing each other, eventually orchestrated by Jan van Vlijmen.

Before I discuss the present release, allow me a few words about the style and musical language in Escher’s music. From early on, his music was repeatedly said to be influenced by Ravel and Debussy. That is only partly true. As Escher put it, “this comes close to stupidity, also because the music of Debussy and Ravel represents separate musical worlds”. He also said that “he felt that his affinity with the toccata-technique of Sweelinck, melismatic Gregorian chant, gamelan music, late-medieval polyphony and with Mahler was as strong as with certain aspects of Debussy and Ravel”. This might suggest eclecticism, were it not for the composer’s sure grip of his material, particularly in terms of design and formal mastery. Out of this varied background, he managed to forge a highly personal style and sound, with which he was able to progress throughout his composing life.

This release presents most of Escher’s chamber output. Absent are: the Violin Sonata (1950; review), the substantial Sonata concertante for cello and piano (1943, revised 1979), the Flute Sonata (1979, his last piece), the superb String Trio (1959, available on Brilliant Classics 95967). Also, some piano works: the Piano Sonata (1935), the Piano Sonatina (1951) and Arcana (1944), perhaps his most important and substantial piano work. But this is a fairly comprehensive survey of Escher’s achievement, and an opportunity to explore music from all periods of his creative activity.

The Trio d’anches for oboe, flute and bassoon, an early work, may still be fairly Gallic in outlook and tone. The Sonata per violoncello solo is rather more austere, but the music eschews gratuitous virtuosity in favour of melodic warmth and feeling. The much later Sonata for clarinet solo is once again a beautiful display of technical mastery and well-meant expression. The Sinfonia per dieci strumenti is scored for string quintet and wind quintet with oboe d’amore replacing the more traditional oboe. The structure is roughly that of a traditional, compact symphony in four movements, playing for a quarter of an hour. This is the only work here in which I have spotted some influence of Balinese music. The writing is as assured as ever, and clearly the product of a musician in full mastery of his aims and means.

The second disc begins with the first recording ever of the imposing Passacaglia for organ. As expected, this sombre piece is at times redolent of Frank Martin or, should I say, in the same vein. Why on earth has this fine work not been heard more often?

Escher may not have been influenced by Ravel, but he retained a deep affection for his work. As early as in 1940, he planned a Sinfonia in memoriam Maurice Ravel, of which only the Largo survives; it has been published and recorded. Some time later, he composed Le Tombeau de Ravel scored for flute, oboe, violin, viola, cello and harpsichord. The title clearly alludes to Ravel’s Tombeau de Couperin. The impulse was a visit Escher paid to Ravel’s house in Montfort l’Amaury. The work is a suite of movements with titles related to Ravel’s work – such as Pavane, Forlane, Sarabande and Rigaudon – shared between soloists (cello in Air, flute in the second Air) and ensemble. The music, a clear and sincere homage to the French composer, avoids the least touch of blunt imitation or pastiche. The Tombeau may be one of Escher’s most popular chamber works.

Escher’s chamber works often carry traditional titles, even if the layout or the scoring strongly differ from the more usual patterns. That includes Quintetto a fiati in which flute doubles alto flute, clarinet doubles bass clarinet, and the oboe part again goes to oboe d’amore. This is another compact piece in three movements with not a single note wasted, and a fine example of Escher’s mature music making.

The last work in this well-filled survey of Escher’s chamber output is the late Trio for clarinet, viola and piano, another fairly large piece of music. Formal mastery and expressive strength go hand in hand. As in most of Escher’s works, form is always strictly controlled but never at the expense of expression. The Trio has a deeply moving autumnal character.

Most works here have been recorded before, for Donemus among others. But it is good to have the present cross-selection available, especially in performances carefully prepared and impeccably played by members of the Gruppo Montebello conducted by Henk Guittart. He is also the author of the insert notes. Full marks for all concerned. I sincerely hope that this well-filled release will convince music lovers to investigate Escher’s excellently crafted and always rewarding music, still all-too-easily overlooked.

The Donemus recordings have been reissued by Brilliant Classics (3 CDs, 95967). This desirable set includes Musique pour l’Esprit en Deuil, the Concerto for String Orchestra, the Trio à cordes, and a generous selection of Escher’s choral music sung by the Netherlands Chamber Choir.

Hubert Culot

Help us financially by purchasing from

The Gruppo Montebello:

Ingrid Geerlings (flute, alto flute)

James Austin Smith (oboe, oboe d’amore)

Alan R. Kay (clarinet, bass clarinet)

Ron Schaaper (horn)

Dorian Cooke (bassoon)

Xenia Gamaris (violin)

Anna Yanchishina (violin)

Ksenia Zhuleva (viola)

Petr Karetnikov (cello)

Rebecca Fransen (double bass)

Dirk Luijmes (harpsichord)

Gideon den Herder (cello, in Sonata per violoncello solo)

Anna da Silva Chen (violin, in Tombeau de Ravel)

Kimi Makino (viola, in Tombeau de Ravel and Trio for clarinet, viola and piano)

Anna Litvinenko (cello, in Tombeau de Ravel)

Ellen Corver (piano, in Trio for clarinet, viola and piano)