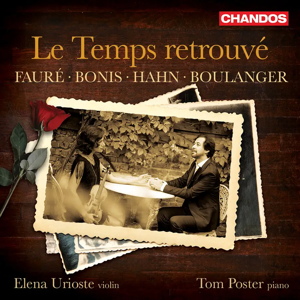

Le Temps retrouvé

Mel Bonis (1858-1937)

Violin Sonata in F sharp minor, Op.112 (before 1914?)

Gabriel Fauré (1845-1924)

Violin Sonata No.2 in E minor (1916-1917)

Reynaldo Hahn (1874-1947)

Violin Sonata in C major (1926)

Lili Boulanger (1893-1918)

Two Pieces for Violin and Piano: Nocturne (1911)

Elena Urioste (violin), Tom Poster (piano)

rec. 2023, Potton Hall, Dunwich, UK

Chandos CHAN20275 [71]

There’s some focused programming here; the three sonatas were published during the years 1916-1926. The husband-and-wife team of Elena Urioste and Tom Poster perform Fauré’s less-recorded Second Sonata, Reynaldo Hahn’s oddly constructed but attractive work as well as the Sonata of the increasingly recognised Mel Bonis.

The programming follows the compositional date of the three sonatas so let’s follow suit. Bonis’ work was probably written prior to the outbreak of the First World War and preserves those qualities of rhapsodic lyricism that make her music so immediate and attractive to contemporary listeners. Bonis is astute in giving strong material to both players – the piano’s ripe chording is as attractive in its way as the violin’s elegant rhapsodising – and there is a genuinely Fauréan warmth and playfulness in the work. The slow movement is based on a Greek theme, withdrawn and intimate, though if you’d told me it was Eastern European in origin or even Chassidic, I would believe you; there is a similar commonality in cadences. The finale is full of airy vitality and brings the work to a rousing close. This isn’t the first time it’s been recorded as there is a competing version on Toccata which takes a slightly more leisurely approach to the opening movement, one on Avi that stretches the slow movement, and another on Klarthe that is similarly indulgent – or generous – in both last two movements. My money is on Urioste and Poster.

For some reason Fauré’s Second Sonata has always been considered the problem child of his late chamber music but a fine performance – as this one is – serves only to convey the compressed and focused nature of his lyricism. Urioste and Poster are careful to delineate their exchanges, not least in the central Andante, and to bind the lyricism, as well as to serve the harmonic implications of the music. There are other ways to interpret the occasionally clotted nature of the writing as Grumiaux and Crossley show by taking consistency fast yet flexible tempi. Urioste and Poster more resemble the great French duo, Amoyal and Rogé, who take slightly more reserved tempi but similarly glisten with expressive intensity.

Reynaldo Hahn’s unconventional 1926 sonata – two substantial outer movements surrounding a zippy scherzo subtitled ‘12 C.V. 8 Cyl. 5000 tours’, as the movement was based on a very fast car ride – is largely distinguished by the instruction calme or indeed très, très calme. The Chandos pair luxuriate in these frequent instructions and draw out the sonata’s nostalgic, chanson generosity in a way similar to Tamsin Waley-Cohen and Huw Watkins and the team of Denis Clavier and Dimitris Soroglov. However, those who know Denise Soriano’s 78rpm recording with Daniel Sternberg, or even her live 1959 account on Meloclassic with Jeanne Marie Darré, will miss Soriano’s edgy-toned, stylistically refined playing as well as her sense of the music’s quivering intensity. Urioste and Poster are not exactly inert and they do flare into life, buttressed by an excellent recording, but I much favour Soriano’s flexible vitalisation of what can be, in other hands, all-too-often a sequence of lovely tunes. Her tempo in the finale, for example, binds the music together. Urioste and Poster, by contrast, come to a full stop – one could almost think the sonata has finished – and then resume for the charming songful pages.

The envoi is the only non-sonata, Lili Boulanger’s Nocturne, from her Two Pieces for Violin and Piano and probably the best-known and most recorded of all pieces here. Its deft warmth offers an appropriate ending.

The booklet documentation is full and there is a note by the performers too. This finely played and recorded recital offers Gallic pleasures across the decade in question and my occasional quibbles – especially regarding the Hahn – are more personal observations than criticisms per se.

Jonathan Woolf

Help us financially by purchasing from