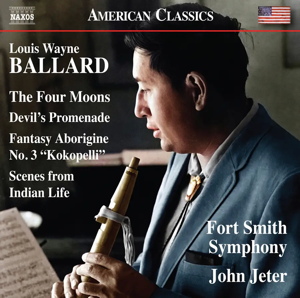

Louis Wayne Ballard (1931-2007)

Devil’s Promenade (1973)

Fantasy Aborigine No.3 ‘Kokopelli’ (1977)

The Four Moons (Pas de Quatre) (1967)

Scenes from Indian Life (1994 version)

Fort Smith Symphony/John Jeter

rec. 2023, ArcBest Performing Arts Center, Fort Smith, AR, USA

Naxos 8.559923 [57]

I had not heard any of Louis Wayne Ballard’s music before encountering this disc. Given that all four works presented here are receiving World Premiere recordings that is not too much of a surprise. The liner describes Ballard as “the first indigenous North American composer of Art Music” so this release is to be applauded and celebrated. The good news for Ballard is that in John Jeter and his Fort Smith Symphony he has passionate and committed advocates and his music receives vibrant and energised performances which have been well recorded and produced in the rather resonant ArcBest Performing Arts Center. The Wikipedia entry on Ballard is considerably more extended than the Naxos liner and worth reading if only to be appalled at the institutional racism Ballard faced especially in his early years including persecution by schools for having the “temerity” to want to speak his native language. His ongoing influence – way beyond that of just composing music can be gleaned in this article on the Chicago Symphony website.

The Naxos liner states; “Ballard’s compositional style was eclectic and likened to that of Shostakovich, Prokofiev and Bartók…. his works contain a mix of tonal approaches with tonal and atonal elements.” My first reaction to these scores is that they are enjoyable without being especially revolutionary in their Art Music sense – I cannot say I hear much/any influence of those three mentioned composers. Of course by integrating indigenous North American music into ‘Classical’ music genres for the first time it is significant and worthy of serious consideration – but that does not make it great. As well as a composer Ballard was an important performer (percussionist and dancer) and ethnological collector of the music of his people. But he struggles as all such ethnologists did to incorporate the unique richness of those cultures into the norms and conventions of Western Art Music. Simply put; how do you notate the infinitely subtle variations in rhythm and pitch – let alone instrumentation – in a way that can be effectively performed by a symphony orchestra. Western non-graphic notation “squares off” these vital nuances in a rather debilitating way. This dilemma has faced every ethnologist and arranger of ‘folk music’ for the last two hundred years and beyond. Ballard’s solutions are no better – or worse depending on how you view such transcriptions – than any others. One thing that Ballard does do is incorporate a significant number of indigenous percussion instruments into the scores. These are well-realised in this new recording but I am not sure if they have quite the effect or impact that Ballard intended. Rather than dominating the sound and feel of this music they have the effect of bolted-on local colour. So the Devil’s Promenade that opens the disc starts with interesting percussion led textures but this soon is overwhelmed by Ballard’s rather heavily score full orchestra and it takes a more informed ear than mine to discern the differences between cow-horn or sea-shell rattles, water, war or Dakota drums – all of which feature in the score. The title is in fact the name of an area of Oklahoma where Ballard was born.

As well as his use of indigenous instruments, Ballard borrowed melodic material as well. Of course for the uninformed listener such as myself it is hard to know exactly where original Ballard ends and collector/arranger Ballard starts. My main issue with this work is the heaviness of the instrumentation – well played and recorded here though it is. To my mind Ballard is considerably more successful elsewhere on this disc when he thins the textures to far greater effect. The Fantasy Aborigine No.3 ‘Kokopelli’ is also prone to dense orchestration. This is one of a series of six similarly titled works where each work focuses on the mythology of a different North American tribe or area. The use of the term Aborigine is in the sense of “ethnic groups who are the earliest known inhabitants of an area” rather than the usage linked to the indigenous peoples of Australia. Kokopelli of the title is the God of Music in Native North America. Again multiple unusual percussion instruments feature although whether they have a narrative or simply add instrumental variety to the soundscape is unclear. Indeed in both of these works there does not appear to be any specific narrative. Not that there needs to be but I did struggle to understand quite what the music meant except as a sampler of this music in orchestral garb.

The main/longest work on the disc is the 23:25 minute ballet The Four Moons (Pas de Quatre). Ballard’s wife Ruth contributed the following programme note for its 1967 premiere quoted in the liner; “The composer, Louis W. Ballard, created a suite of classic dances, combining the traditional European dance forms with modes and rhythms associated with Indian tribal music. Each dance embodies the authentic spirit of the tribe of each ballerina, conceived through the contemporary style of the composer. This allowed the four separate dance dramas, according to the individual style of each ballerina and the distinctly varied tribal characteristics … The Four Moons, symbolizing the four ballerinas whose tribal ancestors reached Oklahoma Territory from four different directions has significance in Indian mythology as The Four Seasons, or Four Directions of life. The Four Moons dance in the ceremonial dances of the powwow. Hypnotized by the intoxicating spell, they assume the spirit of their tribal ancestors.” Musically the work is divided on this disc into eight sections which is simply an opening “Overture”, an entrance and dance of the four ballerinas, an individual dance for each dancer/tribe and a closing “pas de quatre”. Curiously no mention of the work’s choreographer is made but the original dancers (there were Five Moons not four but Maria Tallchief retired from dancing in 1966 – Ballard dedicated the Osage variation to both Tallchief sisters) were important trailblazers for Native Americans in the ballet world.

This was Ballard’s third ballet so clearly he identified with the genre although again it would have been interesting to know the specific choreographic vocabulary used. Four of the “Five Moons” had danced with the famous Ballets Russe de Monte Carlo and the fifth was married to George Balanchine so clearly they all had rock solid classical techniques while embracing elements of what would now be known as contemporary dance. Each of the solo variations allow Ballard greater musical variety than was present in the two preceding orchestral works. As is the norm with this style of “Divertissement” ballet there is no story as such just varied/contrasting dances for soloists and groups. According to the liner “rhythmic motifs, derived from the dances of numerous tribes underpin his music. As a score it is quite attractive and certainly seems like a good vehicle for dance. I suspect that the true cultural significance and importance of the work lies in the dancers for whom it was written and their achievements. The music alone is less noteworthy once one acknowledges Ballard’s place in the development of such music.

The final work on the disc is the shortest [the four movements together only total 9:30], the most light-hearted but also – to my ear at least – the most effective in purely musical terms. The Scenes from Indian Life are a kind of pencil sketch of events Ballard witnessed from his home in Santa Fe. Two Indian neighbours collaborated on building a wall outside his house. The first three movements – totalling just 5:30 – were written in 1963 with a new 4:08 finale titled Feast Day added three decades later. In the opening movements Ballard achieves a witty and effective portrait of these neighbourly friends using much lighter and precise orchestration than elsewhere on the disc. But this is most certainly a case of less is more. The closing Feast Day rather reverts to Ballard’s busy and sometimes cluttered orchestral style but it does make for an uplifting conclusion to the disc.

As my only exposure to Ballard’s work it is of course impossible to know how representative these works are of his entire output. It is undoubtedly true that some Artists or Art can be significant by its place in the evolution of the art form it represents – so there is an importance in primacy that does not always have to equate with greatness. I can absolutely appreciate why Ballard’s music is important to the cultures it celebrates as well as to the composers that followed and were inspired by him. But for an outside observer this is attractive rather than ‘great’ music. But credit to John Jeter, his enthusiastic orchestra and Naxos for bringing these appealing scores to the wider world.

Nick Barnard

Help us financially by purchasing from