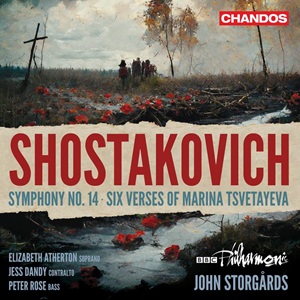

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975)

Six Verses of Marina Tsvetayeva, Op 143a (1974)

Jess Dandy (contralto)

Symphony No 14, Op 135 (1969)

Elizabeth Atherton (soprano); Peter Rose (bass)

BBC Philharmonic/John Storgårds

rec. 2022, MediaCityUK, Salford, UK

Chandos CHSA5310 [75]

The 11 movements of Shostakovich’s Fourteenth Symphony are settings for soprano and bass voices of poems in Russian translation by three different non-Russian poets, Federico Garcia Lorca, Guillaume Apollinaire and Rainer Maria Rilke, plus a single setting of the Germano-Russian Romantic poet, Wilhelm Küchelbecker. It was only late in the day that the composer decided to add it to the numbered sequence of his symphonic works, and, given its remarkable cohesion, we should have no problem with that. The score specifies an orchestra of 19 strings plus a wide selection of percussion instruments (without timpani) and celesta. The work’s theme, and subject, is death: this is a sombre work indeed. It is dedicated to Benjamin Britten, who conducted the first performance outside the Soviet Union at the Aldeburgh Festival in June 1970, a performance issued on IMG/BBC that can occasionally be found second-hand. Britten later returned the honour with the dedication of his third church parable, The Prodigal Son. Both composers were of fragile health – much of the symphony was composed in hospital – and Shostakovich died on 9 August 1975, Britten on 4 December the following year.

The text of the first song, ‘De profundis’, is a typical Lorca meditation, fusing death with the Andalusian landscape. In the second, death stalks an Andalusian tavern. Six Apollinaire settings follow. The first is a retelling of the Lorelei legend, then three lilies symbolise a poet’s suicide. Shostakovich’s preoccupation with the military march is in evidence in ‘On watch’, whereas ‘Madam, look!’, in which the soprano is required to sneeze, lets us briefly into Shostakovich’s characteristically sardonic humour. Apollinaire describes his experiences at the Santé prison in Paris in the following song, and a sound knowledge of Russian history would be useful to deconstruct the dismissive and insulting message the Zaprogue Cossacks send to the Sultan of Constantinople in the final setting. The symphony ends with two settings of Rilke. Music from the opening of the work returns in ‘The Poet’s Death’, and the second, the shortest movement of all, and the only one in which the soprano and the bass sing together, is well described in the booklet as Shostakovich shaking his fist at death ‘in impotent rage’. Between the Apollinaire and Rilke settings is placed the single Küchelbecker setting, a poem addressed to his close friend and fellow poet, Anton Delvig. It deals with the immortality of art, so the suggestion that this song was meant as a direct message to the symphony’s dedicatee is difficult to resist.

This performance, the third Shostakovich symphony from Storgårds and the BBC Philharmonic, is outstandingly fine. Peter Rose and Elizabeth Atherton have made something of a speciality of the work, and it shows. Rose is dark and imposing, acting well with the voice, beseeching, for instance, in the Lorelei story. He is deeply moving in ‘O Delvig, Delvig’, singing with a tenderness appropriate to the only song that offers some little respite from the gloom. The accompaniment, in a warm D-flat major, is allotted almost exclusively to divided cellos and basses, enhancing the atmosphere of sweet consolation. ‘Lorelei’ allows Elizabeth Atherton to demonstrate her mastery of the twin demands of this most demanding score. There is, on the one hand, the near-demented expressionist narrative as she impersonates the ‘blonde sorceress’ who bewitches so many men; on the other, reflective tenderness near the end, taken very slowly, as she perceives her lover arriving in his boat. The first of these qualities is also spectacularly demonstrated in the second song, ‘Malagueña’. For the work’s first performance, the soprano part was taken by Galina Vishnevskaya, as it also was at Aldeburgh. The music was likely conceived with her voice in mind, or a voice very like hers, and some may miss the extremes of her vocal performance. I believe that both approaches are valid, just as I do when I hear that the other songs can only really be properly sung by a Russian bass. Both singers score highly on finding the right notes, a challenge in itself. And as for the Russian text, one is lost in admiration of their delivery, especially in the faster passages.

The scoring is spare but remarkably varied, with percussion – the xylophone especially, as so often in Shostakovich – adding important colour. The string writing is frighteningly exposed in places. A particularly fiendish moment in ‘Malagueña’, for example, requires the first violins to leap more than an octave to attack a rapid phrase beginning on the E two octaves above the instrument’s highest open string. Every orchestra struggles here – the challenge is surely meant to be heard – but no other ensemble is more successful in my experience. A special word must go to principal cellist, Peter Dixon, for his wonderfully expressive playing in the fourth song, ‘The Suicide’, where he alone accompanies the soprano for long periods. Another high point among many is the superbly controlled and powerful crescendo from the tom-toms, pp to fff, at the end of the fifth song.

The Fourteenth Symphony is a work that inhabits the mind and lingers there. It has inspired its performers, with many recorded versions that can be confidently recommended. Britten’s live performance is an important historical document that should always be available. The English Chamber Orchestra accompanying Vishnevskaya and Mark Rezhetin under Britten’s inspired direction is not to be missed – though the bronchial audience in the moment of silence before the short final song is deplorable. I admire particularly Bernstein’s performance from 1976 (Sony) with Teresa Kubiak and Isser Bushkin. Vassily Petrenko’s Naxos performance from Liverpool, with Gal James and Alexander Vinogradov in a super-analytical recording, is also a particular favourite. But this new performance is the equal of them all and surpasses more than one. No listener who feels as strongly about the work as I do should miss it.

The disc is enhanced by the coupling. By any standards, the life story of Marina Tsvetayeva is grim indeed. Shostakovich’s settings of six of her poems – he referred to them as a Suite – was one of his last works, composed first for contralto and piano and first performed at the end of October 1973. Shostakovich later made the arrangement for chamber orchestra performed here. He chose poems that allowed him to explore themes that had preoccupied him throughout his life, providing a wider range of subject matter and thought than is found in the Fourteenth Symphony. The first song, ‘My verses’, has the poet reflecting on her own neglected early work. The accompaniment is string-dominated, but as the poet imagines her poems languishing in ‘dusty bookshops … where nobody buys them’ a celesta – another Shostakovich fingerprint – is added to the mix. Then, as the song reaches its conclusion, the poet’s fragile conviction that her early work will one day be valued is supported by a single, heroic horn. Jess Dandy, a real contralto and ideally suited to the work, is quite magnificent here, her voice rising in a kind of uneasy triumph.

The second, ‘Whence such tenderness’, might be read as a simple love song. A sweetly oscillating figure in the accompaniment is reminiscent of the final movement of the 13th Symphony. Dandy lightens her voice beautifully for this song, so tender, yet so wistful. It ends on major chord, albeit slightly corrupted. ‘Dialogue between Hamlet and his Conscience’ is the last of Shostakovich’s many encounters with Shakespeare’s play. Hamlet’s bewildered indecision – do I love her? I did love her – is accompanied by obsessive, repeated notes, while Dandy adopts a flat, dead tone the better to represent Ophelia who lies ‘covered with weeds’.

The fourth and fifth poems pay homage to Pushkin. Their particular theme is described by Malcolm MacDonald in a wise chapter about Shostakovich’s late vocal works in Shostakovich: The Man and his Music (ed. Christopher Norris, 1982) as ‘the creative artist ranged against the tyrant – Pushkin against Nicholas I’. In the first, ‘The Poet and the Tsar’, a xylophone brilliantly represents, first, the Tsar, majestic in gold regalia, and second, his brutally repressive reign. ‘No, the drum did beat’ is a narrative poem recounting the procession as Pushkin is carried away after the duel with his brother-in-law that will bring about his death two days later. Just listen to the rising anger in Dandy’s voice as she tells us that the Tsar hypocritically brought in so many officials to bear the poet away that there was no room, neither at his head nor his feet, for his friends. This is a towering performance from Dandy, and she is just as fine in the bell-dominated final song. This is a heartfelt tribute to Anna Akhmatova (1889-1966) a poet deeply admired by both Tsvetayeva and the composer. The bells are those of Moscow, a city Tsvetayeva wills to Akhmatova, along with her heart, in the penultimate line of the poem. Dandy soars in the broad, assertive passages, and is deeply moving as the work winds to a gentle, major key close that cannot, nonetheless, be described as positive or optimistic. The orchestral playing is again outstandingly fine, authentic and committed. Storgårds is as inspired here as he is in the symphony.

The Tsvetayeva settings in their orchestral guise are less austere and more approachable than the piano version (of which Lyubov Sokolova and Yuri Serov give a fine performance on Volume 2 of the complete Shostakovich songs, issued by Delos in 2002.) The richness and depth of the recorded sound adds to that. David Fanning provides an authoritative essay in the booklet, where the performers’ details are also to be found. Each member of the orchestra is named, and rightly so, though only for the symphony, which means that the wind players in the Tsvetayeva settings miss out. Texts and translations are not provided, however, and this is a grievous error. No non-Russian speaker will have the slightest idea of what is happening in the symphony, and an understanding of the Tsvetayeva texts is crucial to any appreciation of the work. They can be found online – though a fair amount of hunting down is required – but what is needed is a transliteration of the Russian texts with a side-by-side translation. Its absence in an otherwise magnificent issue is highly regrettable.

William Hedley

Previous reviews: Nestor Castiglione (June 2023) and David McDade (October 2023)

Help us financially by purchasing from