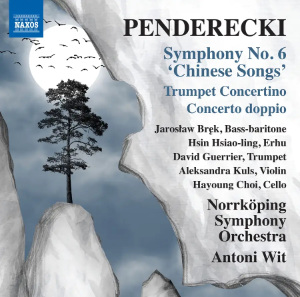

Krzysztof Penderecki (1933-2020)

Trumpet Concertino (2015)

Concerto doppio for violin, cello and orchestra (2012)

Symphony No. 6, ‘Chinese Songs’ (2017)

David Guerrier (trumpet)

Aleksandra Kuls (violin); Hayoung Choi (cello)

Jarosłav Bręk (bass-baritone); Hsin Hsaio-linh (erhu)

Norrköping Symphony Orchestra/Antoni Wit

rec. 2022, Louis de Geer Konsert & Kongress, Norrköping, Sweden; Bauhinia Musik Haus, Hong Kong

Texts and translations supplied

Naxos 8.574050 [61]

Penderecki began his Sixth Symphony in 2008 but only completed it in 2017, by which time his seventh and eighth symphonies, his final essays in that form, had already seen the light of day. The work runs for a little under half an hour, and is in eight short movements, settings for baritone and orchestra of Chinese poems, 8th-century for the most part, sung in German adaptations by Hans Bethge. There is an important part for the erhu, a Chinese bowed stringed instrument.

My first encounter with Penderecki’s music was a performance of Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima by the Hallé Orchestra in Manchester in 1969 or 1970. This was followed by the opera The Devils of Loudon in London two or three years later. This young music student had never suspected that such music could exist! Other music from the composer from that time confirmed the shock value of his employment of extreme avant-garde techniques. With the passage of time, however, Penderecki’s engagement with older music led to a gradual modification of his style, less confrontational and with greater use of tonality. This is an oversimplification, but will serve to explain to those who only know Penderecki from his earliest works why this symphony sounds so different. Though unmistakeably contemporary, tonality is never far away.

Hans Bethge will be a familiar name to listeners who know Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde, for it was his adaptations of Chinese poetry that Mahler set to music. But there are is far more drama in Das Lied than in this symphony, where the poems chosen are principally reflective in mood. The third movement, ‘On the river’, for instance, is a simple love song. The poet, in his boat – a journey vividly yet discreetly pictured in the orchestral accompaniment – sees the sky reflected in the water and thinks of the beloved’s place in his heart. The music is lovely, a pleasure to listen to even on a first hearing, an observation that can be applied to the whole work. Other songs are darker in mood, and the finale, which evokes the profound nostalgia of a traveller far from his native land, is sombre, even tragic. The subject is treated – and this is how the symphony ends – with understated restraint.

In setting these texts Penderecki successfully avoids any charge of artificial chinoiserie. Instead, four interludes between the songs are played, unaccompanied, on the erhu. The instrument has only two strings, and Hsin Hsiao-ling, a celebrated exponent, plays with a light vibrato on longer notes and inserts a few discreet slides. There is a flute-like quality to the sound, but you would know you were listening to a stringed instrument. Its music is pentatonic – think of the black keys on a piano – and evinces a somewhat melancholy atmosphere. As far as one can judge a musical culture so unfamiliar, her performance is very successful. With the singer we are on more safer ground. Jarosłav Bręk’s voice is a magnificent instrument, fairly dark in timbre, but particularly rich and sweet. The music mainly requires him to spin a beautiful, smooth line, and this he does superbly well. I was so taken with his singing that I determined to watch out for him elsewhere, so it was a shock to read that he died in April 2023 at the age of 46.

The Trumpet Concertino earns its title by its brevity – 11 minutes – but it is quite an imposing work. An introductory side-drum roll is followed by a preparatory fanfare from the soloist, apparently offstage. A second drum roll launches the first movement proper, martial in character with much use of dotted rhythms in exchanges between the solo instrument and the orchestra. The musical language is more advanced than in the symphony: there are moments when Shostakovich seems not too distant. A short phrase from the flute ushers in the second movement, Larghetto, more tonal, and even, at the outset, romantic in nature. The soloist duets with wind principals over a background of strings. The third movement lasts a little over a minute before the rapid finale that provides the soloist with a fair amount of virtuosic display. The ending is abrupt and determined. The work’s dimensions are well-suited to its title, but I could have listened for longer. The French soloist, David Guerrier, not yet 40, plays with a rich, mellifluent tone and his technical skills are much in evidence, especially in the finale. (He also plays the horn to the same exalted standards.)

The Double Concerto lasts almost twice as long as the Concertino. It is in a single movement, and several hearings are needed before one begins to perceive the form. The soloists meander slowly at the opening, with high harmonics and pizzicato notes over a held note from a single double bass. Only after about 2½ minutes does the orchestra make its first appearance with a series of dramatic chords. Most of the musical material is of a violent nature, making the work a more challenging listen than the Concertino. Two calmer interludes occur before the midpoint, with singing lines for both soloists over held, diatonic chords from the orchestra. But neither of these lasts, as the relationship between the soloists seems to be one of competition, even conflict, where in fast, scampering music, scraps of themes are tossed about between them. This is angry music, even more forceful in a later cadenza. Following this, however, a slow, diatonic melody with wind and bell sonorities is clearly meant to lead us to the end. I don’t think many listeners will hear reconciliation here, but as the two solo instruments climb to the upper reaches there is, in this highly effective and affecting ending, something like acceptance and resignation. There is but little opportunity for either soloist to display a sweeter side, but the extreme technical virtuosity required is amply furnished by Polish violinist Aleksandra Kuls and South Korean cellist, Hayoung Choi.

The playing of the Norrköping Symphony Orchestra cannot be faulted, and Antoni Wit’s extensive discography for Naxos is witness to his mastery of contemporary Polish music as it is throughout the repertoire. The sung texts are given in German with an English translation alongside, and Richard Whitehouse provides a descriptive listening guide. The recorded sound is excellent.

William Hedley

Help us financially by purchasing from