Déjà Review: this review was first published in November 2002 and the recording is still available.

Luigi Cherubini (1760-1842)

Medea (1797)

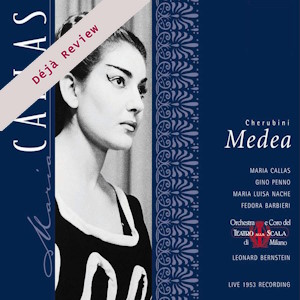

Maria Callas (Medea), Fedora Barbieri (Neris), Maria Luisa Nache (Glauce), Gino Penno (Giasone), Giuseppe Modesti (Creonte), Angela Vercelli (Prima ancella), Maria Amadini (Seconda ancella), Enrico Campi (Capo delle guardie)

Chorus and Orchestra of La Scala, Milan/Leonard Bernstein

rec. live, 10 December 1953, La Scala, Milan

Originally reviewed as EMI release

Warner Classics 5679092 [2 CDs: 129]

Like the Callas “Andrea Chénier” which I have just finished reviewing, the set bears the warning “The technical imperfections of the original recording mean that the sound quality of this live performance is not of the overall standard normally to be expected”. Frankly, I think EMI are shooting themselves in the foot here, because anyone who has persevered with the very poor sound of the “Chénier” and imagines more of the same (for an opera that Callas recorded in the studio anyway) is going to walk right away. Again, we are not told where the recording came from, but this time it is perfectly in line with other live recordings from the early 1950s in the Italian Radio archives and, if the source was not Italian Radio itself then it must have been a re-broadcast well into the FM era. The sound is limited, a little boxy, but real patches of distortion are confined to the choral scenes and Callas’s top C at the end of Act 2. Otherwise the voices are reasonably well caught and even the orchestra can be appreciated. In short, while a Walter Legge-made studio production from 1953 would have been better, not all studio recordings from this time made by other companies necessarily were and I should have thought that anyone prepared to countenance at all a live performance from nearly fifty years ago will be pleasantly surprised at how trouble-free it is.

“Medea” was an opera to which Callas attached particular store and she notched up a total of 31 performances, quite a lot for an opera which is not everyday fare (all this information, and much else, is to be found in the booklet). Her first performance had taken place earlier the same year, 1953, in Florence under Vittorio Gui. The meeting with Bernstein was a chance one, for the original plan was to present Alessandro Scarlatti’s “Mitridate Eupatore” under Victor De Sabata. However, De Sabata fell ill and, in view of the success of “Medea” in Florence, the decision was made to present this instead. Gui was otherwise engaged and so Maria Callas herself, who had been listening to a recent broadcast concert conducted by Bernstein, suggested that the young American might be invited to conduct.

It was a hunch that worked. Bernstein had done very little in the opera house and had to learn “Medea” in five days. That being so, I can only say that the results are a tribute to his genius – there is no other word for it. I can conceive that a well-versed musician might swat up this score in five days and, with the backup of the orchestra’s and singers’ experience, carry off a decent “traditional” performance. But Bernstein in those five days made the score his own, conceiving and then triumphantly bringing off a dramatic vision which must have come as quite a shock to Milanese ears in 1953. As for Callas, she clearly feels free to throw herself into the plight and the complex psychological state of Medea without let or hindrance. “Bel canto” is put rudely on one side as she lets fly with guttural, savage vowels, snarling chest tones and reckless top notes. She and Bernstein strike sparks off one another from the word go, and this is a singing/acting performance such as the theatre can rarely have experienced.

Furthermore, they inspire the rest of the cast. One’s first reaction is that the other singers are not up to very much, and in the case of the Glauce (who has little do after Medea has come on) I’m afraid that remains so. But Gino Penno and Giuseppe Modesti get caught up in the event and cope more than valiantly when Callas is around.

There were those who found Bernstein’s approach anachronistic (but where were those critics when Furtwängler had conducted Gluck’s “Orfeo ed Euridice” at La Scala two years before, a performance still preserved in the archives?). I’m not so sure. Certainly, if a present day authenticist such as Nikolaus Harnoncourt were to take on this opera (and the sooner he does the better) then I might expect that, unafraid of extremes as he is, something akin to Bernstein’s bristling energy, his sharp characterisation of accompanying figuration and, at the other extreme, his long drawing out of moments like Neris’s aria with its haunting bassoon solo, would emerge. In one respect, though, I venture to suggest that a Harnoncourt performance would be very different for, while I have referred all along to “Medea” the truth is that there “ain’t no such thing”. Cherubini was working in Paris, his opera was called “Medée” and it followed French opéra-comique convention by carrying the drama forward by means of spoken dialogue rather than recitative. This convention was not, however, normally applied to tragic opera and the work met with no very great success either in Paris in 1797 or (with some changes) in Vienna in 1812. The “Medea” over which both Brahms and Wagner enthused was a revision presented in 1855 by Franz Lachner, who provided his own recitatives in the place of the original dialogue. By a curious irony Lachner, a conservative to the point of self-effacement in his own compositions (in so far as we know them) was inspired by the subject to go in for some pretty modern harmonies which sit uneasily alongside Cherubini’s essential classicism. Incredibly, given the celebrity of the work and our present-day obsession with authenticity, no recording of the opera as Cherubini wrote it seems to have been made (so how about it, Harnoncourt or Gardiner?).

After the run of 5 performances with Bernstein, Callas kept the opera firmly in her repertoire. Still in 1954 she was repeating it with Gui, this time in Venice, and some 1955 performance in Rome under Santini were notable for the presence in the cast of Boris Christoff. Then in 1958 she appeared in a Dallas production under Nicola Rescigno; the mouth-watering cast included Teresa Berganza, Jon Vickers and Nicola Zaccaria. The same team (with Cossotto in the place of Berganza) came to Covent Garden in 1959 while Callas finally brought the opera back to La Scala in 1961 and 1962 under the baton of another American conductor still warmly remembered in Italy, Thomas Schippers. Vickers was again Giasone and the cast also included Simionato and Ghiaurov. Lastly, if you fancy seeing her without hearing her, there is the 1969-70 film directed by Pasolini. It is remarkable how much of all this has been preserved; bootleg versions of a 1953 Gui, of 1958 and 1959 Rescignos (Dallas and Covent Garden) and a 1961 Schippers have circulated. I state this for information and am not able to report on their sound quality. An actual EMI recording was never made but in 1957 a studio version was made for Ricordi under Tullio Serafin with an unexceptional cast and EMI have since adopted it into their Callas canon. All the same, in view of the quite extraordinary artistic meeting it documents, I should be inclined to go for this Bernstein as “the” Callas version from now on.

“Medea” requires the qualities of a true singing-actress. If Callas was reckless with her resources, the subsequent studio history of this opera documents two equally reckless ladies who singed their vocal wings even more badly: Gwyneth Jones (Decca) and Sylvia Sass (Hungaroton). Lamberto Gardelli conducts in both cases. Two other singing actresses, on the other hand, who had the staying-power for a long career can be heard live; Magda Olivero on a bootleg issue in Dallas in 1957 under Rescigno (the same production later joined by Callas) and Leonie Rysanek on an official release from the Vienna State Opera in 1972 under Horst Stein (RCA Red Seal 74321 79595 2). This latter looks like the choice at the moment if you want a reasonably modern stereo version. But I repeat, a properly authentic edition of what Cherubini actually wrote is urgently needed.

Christopher Howell

Help us financially by purchasing from