Déjà Review: this review was first published in November 2003 and the recording is still available.

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

The Creatures of Prometheus, Op. 43 – Overture, Allegretto, Finale (1801)

Coriolan – Overture, Op. 62 (1807)

Leonora – Overture No. 1, Op. 138 (1805)

Leonora – Overture No. 3, Op. 72a (1806)

Egmont – Overture, Op. 84 (1809-10)

Symphony No. 8, Op. 93 – Second Movement: Allegretto (1812)

The Ruins of Athens, Op. 113 – Turkish March (1811)

Franz Schubert (1797-1828)

Marche Militaire, Op. 51 No. 1 (D.733, 1822)

Rosamunde – Overture (D.644, 1823)

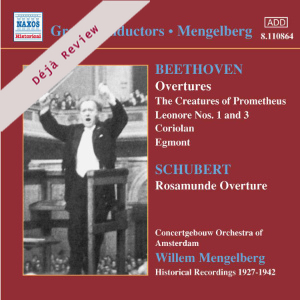

Concertgebouw Orchestra of Amsterdam/Willem Mengelberg

rec. 1927-42, Concertgebouw

Naxos Historical 8.110864 [69]

It seems there’s hardly a field of human endeavour that doesn’t somehow end up spawning sub-cultures hand over fist. Take “historical recordings”, for instance – seeing as that’s the matter in hand. What started out as a simple application of technology, to bring the great performers of the past back into our latter-day living-rooms, now has more departments than Harrods.

At one extreme there’s a subset of collectors who seek out the most analytical restorations, so that they can study and dissect the message. At the other there’s a faction whose greatest pleasure is in comparing different restorations of the same original recording – the equivalent of those audio-oriented “anoraks” who rejoice only in the performance of the medium, and to hell with the message.

In between are those who enjoy the special thrill of hearing the net curtains drawn from over the window of history, but even they come in various shades. One lot demands, “Give it to me straight – hiss, crackle and all!” Another expects the full panoply of digital wizardry, noise elimination combined with “enhancements” – added reverberation, spectral adjustments and what-have-you. To cap it all, there are restoration engineers to suit all tastes.

What’s the “golden mean”? Is there such a thing? If there is, then it’s a ball-park to the middle of which I would reckon that Mark Obert-Thorn’s self-styled “moderate interventionism” comes pretty close. Ideally, and simplistically, we want to be rid of all the “noise” but to keep all the “signal”. Realistically, we have to settle for getting rid of some of the “noise” and keeping most of the “signal”. The art, as ever, lies in getting the balance right.

This brings us to the aspect of this business that I didn’t get round to discussing in my previous review (review). As I see it, the real problem is knowing what, exactly, is this “balance”. After all, as time goes by it’s increasingly likely that none of us – listeners or restoration engineers – has actually heard the original sound, the very stuff by which the engineers of present-day recordings judge the quality of their work. So, what is our reference? Is it the most pristine copy imaginable of the original recording? Yes, but only if you’re of the “Give It to Me Straight” school, and then of course the restoration engineer’s job would be reduced to that of simple transcription. If that were the case, we’d all be brilliant at it! I’ve racked my brains until they creaked, but I can think of no other viable references: ergo I’m forced to conclude that it all comes down to a matter of inference and artistic judgement. Ho-hum – we go all round the houses and it turns out to be completely subjective: the “best” restoration is nothing more than the one you personally believe to be the best.

For this reason, it is impossible to say which of a choice of restorations is the most “truthful”. For someone in my position, that tends to mean, “Never mind the comparisons, judge each on its own merits”. I’m not saying that this is the only way to go about it, because patently it isn’t, but given what I’ve just argued it’s the only way that I’m prepared to go about it. To those who above all else want to know if X’s restoration is “better” than Y’s I can only apologise: other than spotting technical disasters that stick out like sore thumbs, my feeling is that such comparisons are potentially spurious. Let me put it this way: if the top of building A is higher than the top of building B, which building is the taller? The answer is probably, but not necessarily, A, because it depends on where the bottoms of the buildings are. The difficulty is that we aren’t given that crucial information! In passing, perhaps some enterprising company might consider a disc illustrating the art of the restoration engineer, including samples of the unprocessed original along with how it comes out with various sorts of processing? It would at the very least be informative and educational.

Right: on to Mengelberg, the Concertgebouw, 1927-1942, and all that. Firstly the Naxos booklet, as is usual with this series, says little about the music. Instead Ian Julier’s graphic essay quite properly focuses on the performances and their historical context. His last paragraph considers the post-War fate of Mengelberg. As such, it is irrelevant to the immediate subject. However, this sorry postlude does round off the story, and is expressed by the writer with such poignancy and dignity as to earn my gratitude – and, I hope, yours – for its inclusion.

I wish Naxos would explain the logic behind the ordering of the items! They are neither in chronological order of recording – for that, you need to programme the track sequence 8-6-4-5-7-11-1-2-3-9-10! – nor chronological order of composition, nor in any sensible concert sequence. To be fair, given the works on the CD, this last is anybody’s guess anyway, and my guess is that this is exactly what it is (does that make sense?). No matter, CD players are easy enough to programme.

Obviously, the variability evident in the background noises – hiss, granularity, crackle, and so forth – will depend on both the original source media and the degree to which Obert-Thorn doctored, or rather was prepared to doctor, them. For example, tracks 8 (1927, the earliest), 5 (1931), and 10 (1942) sound the worst, whilst the best in this respect are tracks 6 (1930) and 9 (1942). Nostalgia buffs in particular will be relieved to hear that there is never the slightest doubt that we’re listening to “78s”. The really good news for the rest of us is that Obert-Thorn’s “moderate interventionism” has ensured that nowhere does the residual “grot” in the medium obscure the all-important message.

Perhaps the one bit of logic in the programme is the placement first on the CD of the Prometheus overture, inasmuch as we get the worst of the sound over with first – and to be fair it is pretty awful, the loud bits being fairly painful. The problem is distortion, something that I’m afraid not even the Obert-Thorn magic wand can do much about. Still, it does affect only the loudest parts and, as luck would have it, the other two Prometheus excerpts that make up this mini-suite are, on the whole, rather quieter!

Be that as it may, more important is what these remastered recordings – including that relatively painful one – reveal. On the technical front, the microphony was simple but effective, offering a very deep perspective. The strings are very “up-front”, presented with a clarity that immediately makes you sit up and take notice. Taking a sample of the sound of the strings alone gives a strong impression of a somewhat dry and airless acoustic. This is misleading, because once the winds and timpani – and the percussion in the Turkish March for that matter – join the fray, they are set much further back, nestling in the ambient bloom of the Concertgebouw. This is not entirely good news, because it creates a nagging feeling that we’re hearing a string orchestra on-stage with a wind and percussion band off-stage. This is nothing like what we’re used to in present-day recordings where half the players – and all of the woodwinds – seem to be wearing tie-clip mics., and to be honest neither is it what I usually experience in a concert hall.

What we have is an exaggerated perspective, which I suspect is the consequence of using a single microphone “sitting” in the front-row stalls, too close to the strings in relation to the winds and too low down to “see” over the strings to the winds at the rear of the platform. This is not entirely bad news! Firstly, for reasons I’ll come to shortly, it brings the several sections of the strings into sharp relief. Secondly, they say that “distance lends enchantment”, and so it is here: even when playing quietly and with the strings busily accompanying away in front of them, the Concertgebouw’s wonderful winds are “perfectly” audible. Moreover, we eat our cake and have it because, when they’ve a mind to, the winds can and do cut through the texture like well-stropped razors.

That relatively dry focus of the strings is of course invaluable when it comes to serious study, or even simple savouring of the way that Mengelberg sets about his Beethoven. The aural discomfort of the opening distortion is quickly overlooked once the strings start chittering. They have about them a purposeful precision: Mengelberg clearly regarded even streams of semiquavers as crowds of individuals: he and his orchestra must have worked very hard at preserving those individual identities. No matter how tiny the gaps, there is always some perceptible space between consecutive notes. Mengelberg never lets his demisemiquavers degenerate into tremolando, and what a disproportionate difference that little thing makes!

It also puts those swooning portamenti into a proper perspective. Judging by these recordings, and running contrary to popular impressions, these “old-fashioned” portamenti were not applied with wholesale and reckless abandon. Oh yes, give them a ripe romantic tune and sure enough, out will come the portamento like a (rubbery) sword from its scabbard. Ah, but then give them some Beethoven, and suddenly the syrup is applied with immense circumspection.

Yet, for all he seemed to regard Beethoven as having one foot firmly in the Classical age, Mengelberg was equally aware of the disposition of the composer’s other foot. The disciplined metrical precision that characterises the former foot is enlivened by judicious flexibility of tempo and an astonishing degree of attention to hairpin dynamics, weighting, and crescendo. In short, Mengelberg could teach today’s young lions a thing or two about “cooking with gas”.

It’s hardly necessary to go into great detail about the individual pieces, so I’ll confine myself to a sample or two of Mengelberg’s exquisite “cuisine”. In the Prometheus allegretto movement, the variations on the famous “Eroica” theme are direct and unfussy, trotting – occasionally “floating”! – at just the right rate of knots. Ritenuti are not exaggerated, all is in proportion, and very witty. Portamenti are applied with a grace and subtlety that noticeably enhances the musical expression.

The Coriolan Overture, in spite of its brevity, is for me one of Beethoven’s crowning achievements. It “proves” that LvB was practising psycho-analysis donkey’s years before it had even been invented. Mengelberg gets the orchestra to deliver the opening phrases with terrific dramatic weight, and sets a basic pace that is propulsive, rather than rushed (like Munch’s). He imparts great drive and aggression, easing back for the “feminine” bits – which he then engulfs in a rising torrent of ferocious energy. Again, portamenti are used to beautiful and telling effect: listen to this, and you’ll wonder what all the fuss is about!

Turn to the Turkish March, and flexibility takes a vacation – Mengelberg makes it a march to which you could actually march! What’s more, considering that they are emerging from the misty remoteness of the rear of the platform, the percussion come through with a fair old wallop – what must it have sounded like heard from a more sensible vantage-point? A right royal racket, I shouldn’t wonder. Never mind that the bass drum sounds muffled and causes some minor distress to the microphonic transponder, the lowly triangle is a joy to behold!

Zip back to the single movement from the Eighth Symphony, and this time Mengelberg does not leave the “clockwork” to speak for itself, but animates it with considerable cunning. He teases the clockwork with elasticity, graduated stresses and strategically placed portamenti, these last apparently aimed at pointing up through contrast the perkiness of the “clockwork” articulation. In his Producer’s Note, Obert-Thorn says that this movement was set down as a filler side for Cherubini’s Anacreon Overture. It seems that there’s nothing new in the “B-side” turning out to be the hit number!

I’m aware that I haven’t mentioned Schubert. Well, I ought to leave you folks something to discover for yourselves, didn’t I? For this same reason neither will I mention the incandescence that erupts from certain other of the Beethoven items, to scorch the hair off your eyebrows. Make no mistake, Obert-Thorn has again done a sterling job in preparing these masterpieces of the conductor’s art. Once you’re listening, that residual gunge quickly recedes into the background, revealing some truly wonderful music-making and a remarkably complete sound-picture that seems to encompass the entire orchestral spectrum. In conclusion, something has just this minute struck me: almost half of these tracks must contain at least one side-break, and I never noticed, not even a single one. Enough said?

Paul Serotsky

Help us financially by purchasing from