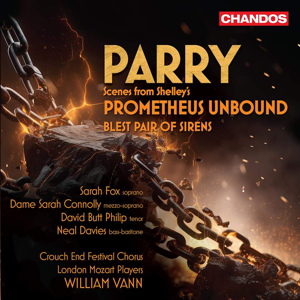

Sir Charles Hubert Hastings Parry (1848-1918)

Scenes from Shelley’s ‘Prometheus Unbound’ (1880)

Blest Pair of Sirens (1887)

Sarah Fox (soprano) – Spirit of the Hour; Dame Sarah Connolly (mezzo-soprano) – The Earth; David Butt Philip (tenor) – Jupiter/Mercury; Neal Davies (bass-baritone) – Prometheus

James Orford (organ)

Crouch End Festival Chorus

London Mozart Players / William Vann

rec. 2022, Church of St Jude-on-the-Hill, Hampstead Garden Suburb, London

Texts included

Chandos CHSA5317 SACD [71]

In 2019 William Vann, working with the Crouch End Festival Chorus and the London Mozart Players made (for Chandos) the first recording of Parry’s Judith (review). Now Chandos have recorded the same forces, albeit with largely different soloists, in another long-neglected Parry work, Scenes from Shelley’s ‘Prometheus Unbound’. The recording of Judith was preceded by a concert performance, which I attended (review); I’m not sure if there was a concert performance of Prometheus Unbound before Vann and his colleagues took the work into the studio.

Prometheus Unbound was commissioned from Parry for the 1880 Three Choirs Festival, held that year in Gloucester, just a few miles from the Parry family country seat at Highnam Court. Parry himself conducted the first performance on 7 September. As Jeremy Dibble relates in his excellent booklet essay, the lead-up to the premiere was a very stressful experience. The rehearsal on the previous day was, to put it mildly, a long affair; it lasted from 10am until 5pm and then resumed at 7.30pm until midnight. Rehearsing way into the night was surely counterproductive but one wonders how much time was wasted correcting copious errors which came to light in the handwritten parts. The chorus consisted of groups from a variety of locations, including a contingent from Huddersfield. Fortunately for Parry, the Huddersfield singers, showing typical Yorkshire commonsense, prevailed on their fellow singers to have an additional chorus rehearsal the next morning. Even so, the performance clearly had its ups and downs, which may have accounted for the mixed reception accorded to the work. It was left to Stanford to come to the rescue. He organised a second performance in Cambridge in May 1881. He ensured that on this occasion there was sufficient rehearsal and, furthermore, by that time Novello had printed proper vocal scores. Stanford’s performance was conspicuously successful and several more performances followed over the next few years. Since the turn of the twentieth century, however, Prometheus Unbound has languished in almost complete obscurity, though the BBC broadcast a performance conducted by Vernon Handley in September 1980.

Before going any further, I think it’s worth setting the work in some kind of context. I was curious to know how much prior experience Parry had had as a composer of large-scale choral and/or orchestral works; so, I consulted Jeremy Dibble’s magisterial biography, C Hubert H Parry. His Life and Music (1992). Dibble includes, as an appendix, a comprehensive list of Parry’s works, divided by genre. He lists just one choral work prior to 1880, the cantata O Lord, thou hast cast us out (1867) and a few church anthems and canticles. As for orchestral works, there are five compositions listed, including one that was premiered at the Gloucester Three Choirs Festival of 1868, but to judge by the titles I don’t think any of these pieces would have been substantial. The sole large orchestral work is the Concerto for Piano and Orchestra in F sharp minor (1878-80), which achieved a first performance in April 1880. I mention all this because it seems to me to indicate that when he sat down to compose Prometheus Unbound Parry was taking a major compositional step forward: he had no experience of writing a work on such a scale (the present performance plays for 61:02). The other point of context to make is that in the years preceding the composition of Prometheus Unbound Parry had visited Bayreuth to see and hear ‘The Ring’ (in 1876) and had met Wagner during the latter’s visit to London in the following year. There are definite traces of Wagnerian influence in this score, though it is unmistakably English in character.

Parry chose to set extracts from Shelley’s four-act lyrical drama Prometheus Unbound (1820). He first encountered this substantial poetic work (which was not conceived as a stage work) in 1879 and it seems clear that it made a strong impression on him. The score which he fashioned is divided into two Parts, the second of which is sub-divided into two scenes. Jeremy Dibble helpfully gives a synopsis in the booklet; this is a highly abbreviated version of that synopsis. In Part I Prometheus is chained to rocks by command of Jupiter. Prometheus has learned that Jupiter will be brought down by his own son but he refuses to reveal this, even when Mercury threatens that the Furies will be unleashed upon him. Mother Earth invokes the Chorus of Spirits, who offer Prometheus some solace. At the start of Part II, we see Jupiter enthroned in heaven, confident in his own powers. His son, Demogorgon (the Male Chorus) appears and announces that he and his father, Jupiter, are condemned to descend into eternal darkness. At this juncture Hercules liberates Prometheus (though this is neither depicted nor specifically referenced in the libretto) and the second scene consists of rejoicing at the happy outcome. I have to say that I find Parry’s libretto doesn’t hang together all that well – for example, the lack of any depiction of the release of Prometheus – and that, I think, is one problem with the work itself.

There’s no avoiding, I’m afraid, the key problem with Prometheus Unbound: the music is uneven. One element that is not uneven is the writing for the orchestra. I only consulted Jeremy Dibble’s work list after I’d finished my listening and I was astonished to be reminded how limited had been Parry’s exposure to significant orchestral writing prior to 1880. The writing for the orchestra is confident and interesting throughout the score. The short orchestral Prelude, for instance, is very well imagined for the orchestra and it sets the tone for orchestration which suggests a far more experienced hand is at work.

The passages set for the vocal soloists are more of a mixed bag, though in this performance all the roles receive top-drawer advocacy. Many of the solo contributions are what I might loosely call set-piece solos, though in Part I there’s an extended dramatic exchange between the characters of Prometheus and Mercury, which works well. Neal Davies is cast as Prometheus. He has to convey the anguish of the enchained hero and also his resolute refusal to accede to Jupiter’s ultimatum. Davies characterises his solos well and has the right vocal presence. His music is dramatic and he delivers it with conviction. We don’t encounter Davies in role for the remainder of the work after Part I, though he is involved in some passages in Part II which are set for the quartet of solo voices. As Mercury, David Butt Philip has the clarity and dramatic power that one would expect from a singer whose roles include Gerontius. The role of Jupiter in Part II is stretching but he is more than capable of meeting Parry’s demands. I find the music which Parry gives to the two female characters is the most convincing. Sarah Connolly is eloquent and consoling as Mother Earth in Part I. In this episode Parry’s music, both for the singer and the orchestra, has a glow which is reminiscent of Brahms – the writing for the cello section is particularly felicitous. The solo role which impresses me most is that of the Spirit of the Hour in Part II, scene 1. Sarah Fox sings it very well indeed. All four soloists represent luxury casting and serve Parry’s music very well indeed.

I’m afraid that the Achilles heel of Prometheus Unbound is the choral writing. The members of the Crouch End Festival Chorus (CEFC) sing with commitment and no little accomplishment but even they can’t disguise the limitations of quite a lot of the music they are called upon to sing. Some episodes are good. For example, the very first time we encounter the choir, singing as Voice from the Mountains (Part I), the writing is imaginative, not least at a rather inspired key change (‘We trembled in our multitude’). There’s also some effective choral writing near the end of Part I (‘Life of Life!’). On the other side of the ledger, though, the Chorus of Furies in Part I really fails to live up to its title, despite the strong attack by the CEFC. As I listened, I couldn’t help but make comparisons with Elgar’s Demons’ Chorus from Gerontius, written only twenty years later: by comparison, Parry’s writing is decidedly tame. In Part II, after the Spirit of the Hour solo, the ladies of the chorus sing as Voice of Unseen Spirits; they sing very well but the music itself is just too polite in tone. What we hear in this passage and in the pages that follow strikes me as very conventional nineteenth-century material and though it’s delivered here with skill and commitment it doesn’t stir me at all. I think part of the trouble is that at this stage in his career Parry was still feeling his way to an extent. I also wonder to what extent Shelley’s words made his task difficult. Reading them, they don’t strike me as ideal material for choral music despite the literary accomplishment. Later in his career, Parry showed that given a suitable text he could set it really effectively, as in Ode on the Nativity or Songs of Farewell. I readily acknowledge that these were much later works but only a few years after Prometheus Unbound Parry showed just what he could do in Blest Pair of Sirens, of which more in a moment. Prometheus Unbound ends with a rousing chorus of rejoicing (‘Then weave the web of the mystic measure’) which provides a big, positive conclusion. Its all a bit predictable, I think, not least in the passages of contrapuntal writing, and this ending doesn’t really convince me. Parry would go on to greater things.

I’m conscious that I have not been able to give as warm a welcome as I might have liked to Prometheus Unbound, even though I admire much of Parry’s overall output. But there’s no point in papering over the cracks; this is a development work, not a neglected masterpiece. That said, it’s important to record that the work attracted some notable championship. I’ve already noted that Stanford was quick to take it up. In his booklet essay, Jeremy Dibble tells us that when in 1905 Elgar delivered his inaugural lecture as Professor of Music at Birmingham University, he specifically referenced 1880, the year in which Prometheus Unbound was premiered as the year when “[s]ome of us who in that year were young and taking an active part in music – a really active part such as playing in orchestras – felt that something at last was going to be done in the way of composition in the English school”. More specific still, Dibble says, was Ernest Walker in his 1907 A History of Music in England, when he asserted: “if we look for a definite birthday for modern English music, 7 September 1880, when Prometheus saw the light at Gloucester and met with a distinctly mixed response, has undoubtedly the best claim.”

So, despite its shortcomings, Prometheus Unbound is an important work in terms of our understanding of both English music in the following few decades and also Parry’s own development. As such, it was important that the work should be made accessible to a wide audience through a commercial recording. Prometheus Unbound here receives the best possible advocacy from four top-flight soloists and an excellent choir and orchestra. William Vann draws everything together with evident commitment to the music and empathy for it. His conducting is purposeful and idiomatic and he inspires everyone to give their best in the service of Parry’s music.

Blest Pair of Sirens is, in many ways, an appropriate coupling but it also offers a stark reminder of the extent to which the Hubert Parry of 1880 still had to develop as a choral/orchestral composer. It’s a much tauter work in terms of structure – Milton’s words undoubtedly help in this regard – and Parry’s choral writing is significantly more assured than was the case in 1880. Blest Pair gets a fine performance here. The CEFC singers really deliver the goods and I particularly approved of the clarity of texture they achieve, even in Parry’s eight-part choral writing. Having sung the piece many times myself, I can attest to their great attention to detail in matters such as dynamics, observance of accents and so forth. William Vann’s conducting is dynamic – he seems determined to banish any Victorian stuffiness. That’s evident from the very start, where the orchestral introduction moves forward purposefully and with a very good feel for the musical line. I like the momentum at ‘And to our high-raised phantasy present’ and the passage beginning ‘Where the bright Seraphim’ is properly exciting. Just occasionally I would have welcomed a little more breadth in the music (for example at ‘O may we soon again renew that song’) but the terrific contrapuntal passage (‘To live with Him’) is exhilarating – and all the more so since all the choral lines are clear. Despite some rather over-exuberant timpani playing, the very end of the piece is majestic and stirring, demonstrating what Parry doesn’t really achieve at the end of Prometheus Unbound.

The presentational standards of this disc are first rate. Producer Adrian Peacock and engineer Jonathan Cooper have recorded the music vividly. The stereo layer of the SACD is very impressive; the sound has impact and presence. The documentation by Jeremy Dibble is excellent.

Notwithstanding the reservations I’ve expressed about Prometheus Unbound this release will be self-recommending – and rightly so – not just to admirers of Parry but also to all who want to explore and better understand the music of the English musical Renaissance. This is an important follow-up to Judith and I hope William Vann and Chandos will be emboldened to do more. Vann has amply demonstrated his credentials as a Parry conductor with this release and the earlier one of Judith. It would be especially welcome if he were to make a recording of Ode on the Nativity, which is surely Parry’s masterpiece in the choral/orchestral genre. There has been a previous recording, by Sir David Willcocks. That’s a fine recording, which has served us very well (review). However, it must be well over forty years old now – the recording date is not specified, but I first heard it in the early 1980s – and a new, modern recording is long overdue.

John Quinn

Previous review: Jonathan Woolf (September 2023)

Help us financially by purchasing from