Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

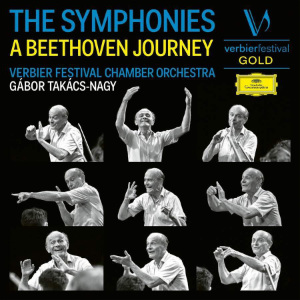

The Symphonies – A Beethoven Journey

Julia Maria Dan (soprano) Ema Nikolovska (mezzo soprano) AJ Glueckert (tenor) Mikhail Petrenko (bass)

Münchener Bach-Chor

Verbier Festival Chamber Orchestra/Gábor Takács-Nagy

rec 2009-22, Verbier, Switzerland and Schloss Elmau, Germany (2&6)

Reviewed as a digital download from a press preview

Deutsche Grammophon 4864117 [5 CDs: 341]

It has become a reviewing cliché to wonder if we really need another cycle of the Beethoven symphonies on record. It is rarer to have a spokesman for the record company involved to wonder it! Not that it has stopped this cycle recorded over 13 years live at the Verbier Festival from emerging blinking into the sunlight. As someone who has no problem with new recordings of much recorded repertoire so long as they have something to say, the question is less should it be released at all as does it justify being released?

Like me, I imagine most readers spent a feverish period, probably during the teenage years, of eating, sleeping and breathing the Beethoven symphonies following that overindulgence with a lengthy fallow period. Possibly, also like me, most readers will harbour a hope that a new recording will reinvigorate those long lost years of fresh, innocent enthusiasm.

This set was recorded over a fairly lengthy period and the producers and engineers have achieved impressively consistent results. The sound picks up a fair few grunts and groans from the podium though it is most interesting to hear the way Takács-Nagy audibly breathes along with the performers.

The cycle gets off to an indifferent start with a perky First which is let down by an absence of a sense of humour in this often misunderstood score. I hear this work as Beethoven adroitly sidestepping the pressure of his first symphonic outing by even out joking Haydn. In this regard, this new version, for all its merits, misses a trick.

Things improve with the Second but here my impression was of a lack of power. This is a symphony that needs to sound like a young lion stretching its muscles. My analytical skills, such as they are, have been unable to work out why this otherwise commendable performance has left me so cold. There is no lack of alertness and vim but somehow the true Beethoven spirit eludes the enterprise.

One of the definite highlights is an agile Eroica that belies its small scale forces to pack quite a considerable punch when needed. Unsurprisingly, given the background of the conductor, the string playing is notable for its attention to detail and its idiomatic solutions to bringing this work to life. In contrast to the Second, here Takács-Nagy nails the necessary combination of fleetness of foot with raw power. In the crunching chords at the climax of the first movement there is nothing whatsoever lightweight about this chamber orchestra performance. The heart of the interpretation is the mighty funeral march where Takács-Nagy’s chamber music detail makes this hoary old score spring back to youthful life. If there is one performance in this cycle that achieves the turning back of the clock to days of youthful enthusiasm for these symphonies then it is this one.

After such a refreshing outing for the Eroica, hopes were high for the Fourth but I struggled with what I found to be an unlikeable view of this most ingratiating of the symphonies. Seemingly determined to make the work the equal of the big bruisers that flank it in the Beethoven canon, Takács-Nagy had me thinking of the brutal treatment regularly meted out to this symphony by Karajan late in his career. I found myself longing for the light and air and exultant zip of Eugen Jochum with the LSO now buried in a big EMI box but still sounding magnificent.

I find the Fifth hard to swallow these days and whilst slimmed down more modern readings such as this one bring some relief from being battered with earnestness as in some older versions, the downside is that the symphony ends up sounding rather like the equivalent of semi skimmed milk. This is a good account of the Fifth but it largely left me unstirred. I had hoped to finally a performance of the finale that was about joy rather tub thumping victory but Takács-Nagy gets a little stuck between the two with the result we don’t really get either.

Whether or not this would have occurred to me if I didn’t know the identity of the conductor, the performance of the Pastoral sounds like one conceived by a string quartet. It isn’t just the small bed of strings used. There is much greater flexibility to the rhythm than one is used to in symphonic accounts of this music. The benefits of this are a sense of greater spontaneity and a liveliness to the detail in Beethoven’s score that is often glossed over. It simultaneously more relaxed and yet more joyful. This Pastoral has real personality from wistful flutes to cheeky clarinets. Furthermore, against this gently bucolic backdrop, the bangs and crashes of the storm really register. A definite highlight of the set, this is one the best Pastorals I’ve encountered.

The Seventh, by contrast, initially stubbornly refuses to hit flight speed. This is a strangely old fashioned view of the work – largely in the worst sense. The tutti in the main section of the opening movement sound like a much bigger band and textures are muddy and sluggish. The mixture of lightness and weight that marked their Eroica goes missing too often leaving a sense of something tethered to the ground. Even the haunting Allegretto second movement which nearly everyone gets right sounds laboured here. Things do pick up considerably with some appropriately zany woodwind playing in the scherzo – bravo to the oboes! The finale is back to the high standards of the best of this set though it does raise an issue with releasing a live cycle such as this. Whilst overall this performance would have sent the audience home happy, in the studio I have little doubt the the opening two movements would have been remade.

The broad tempo of the opening movement of the Eighth put me in mind of André Clutyens’ gloriously expansive version as part of his now largely forgotten Berlin Philharmonic traversal of the symphonies. Many listeners of a certain age will have learnt their Beethoven symphonies from a later issue of this cycle on Classics for Pleasure. I’m not sure I always want to hear this movement taken at this relaxed a tempo but I did enjoy this immensely and the version overall is as easy going and calm as Takács-Nagy and Co.’s version of the Pastoral. If this doesn’t contradict this view, slower speeds also mean greater grandeur in the big moments and the finale is epic in this regard – any illusions that this is lesser Beethoven enthusiastically exploded.

This mellow mood extends to the opening movement of the Ninth. Takács-Nagy trusts in Beethoven to deliver the goods and feels little need to give him a helping hand. The delicate tapestries of woodwind writing that he draws out in Beethoven’s often dense scoring make this movement less severe than usual. But the big D major supernova at the recapitulation is as awe inspiring as one could wish for. This is not a Beethoven 9 concerned with theatrical effects. More so than in the other symphonies, I felt the hand of someone who knows Beethoven from the inside perspective of the quartets at the tiller. This wise, patient approach to the Ninth reflects Takács-Nagy’s exceptional experience and knowledge of the later quartets above all. It is a performance of this enigmatic opening movement that sets high expectations for what is to follow.

This is reflected in the way Takács-Nagy navigates the numerous interpretative bear traps of the scherzo where a smaller body of strings helps him enormously. He knows when to put the hammer down and when to keep things light. For once this movement seems genuinely scherzo like in character but without short changing it. He recognises that very often Beethoven’s most sublime passages are the result of jokes.

I bore myself with vain complaints about playing the great slow movement too fast. Not just because the tempo adopted cannot by any stretch of the imagination be considered an adagio. There is also the practical consideration that if this section is played at this speed either the contrasting andante section has to be played at practically an allegro moderato or, as in this performance, there is no real difference between the two tempo markings. Whilst this latter is definitely the lesser of two evils, it is curious that a performance practice born of a desire to honour the letter of the score should choose to ignore the clear differentiation in the score between the tempi for each section. As it happens this is one of the better attempts at making sense of the faster tempo for the adagio but there is no getting away from the fact that the music is lessened by having the distinction between the two parts of the movement eroded. The conductor moulds Beethoven’s long melodies with consummate wisdom and the resemblances to the late quartets are a joy to hear as he points them out. If the fanfare section toward the end lacks the earth shattering impact it can have at a slower speed – isn’t this part meant to impact on the listener in much the same way as the menacing trumpets at the end of the Missa Solemnis? – at least Takács-Nagy coaxes some suitably rapt responses to it from his strings. The string playing throughout is exemplary and gorgeous to boot.

Given that it can’t command the sheer weight of sound that other versions can, in the finale Takács-Nagy opts for agility and spirit instead. The strings in the initial statements of the main theme make up for lack of substance with emotional intensity. If Mikhail Petrenko’s bass seems a little undernourished it is at least in keeping with the rest of the interpretation. The Turkish March is treated as a comic interlude and the subsequent fugal passage for orchestra becomes a romp. This not only freshens Beethoven’s vision but expands it to include the elements of the absurd we find in the late sonatas and quartets. Takács-Nagy is able to inspire moments of absolute, almost cosmic repose. This is an account of this movement curiously close to the world of Die Zauberflöte. The big stampede to the close is athletic and immaculately stage managed rather than a frenzied rush but still gets the adrenaline pumping. All in all, this is a model of a modern slimline Ninth capable of touching on the depths of this unique symphony.

It was inevitable that this cycle would fall short in some areas. At its best, as in No.s 3, 6, 8 & 9, it brings fresh perspectives and for that alone it justifies its release. The problem would seem to be our unreasonable need for things to be definitive when the nature of music above all other art forms is to resist the definitive. The greatness of Furtwängler’s Beethoven lies in it emerging from performing practices that jettison the definitive in favour of the fugitive moment of inspiration. Such moments are to be had in this new cycle and with them come moments when the Muse remained stubbornly absent. I think this is the only way to perform let alone record these symphonies now. I started this review with a question : does this cycle justify its release. The answer is an enthusiastic if qualified Yes.

David McDade

Help us financially by purchasing from