Joby Talbot (b. 1971)

Like water for chocolate – ballet in three Acts (2022)

Choreography by Christopher Wheeldon

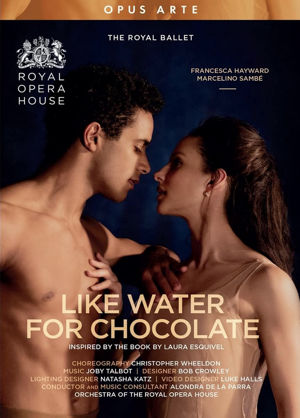

Tita – Francesca Hayward

Pedro – Marcelino Sambé

Artists of the Royal Ballet

Orchestra of the Royal Opera House/Alondra de la Parra

rec. 2022, Royal Opera House, Covent Garden

Opus Arte OA1366D DVD [131]

New work… is vital to the creative health of any ballet company: it ensures that the art form remains relevant in a contemporary and diverse world, it challenges artists to develop new dimensions within themselves and encourages audiences to revisit their preconceptions about what dance can be. [Deborah Bull The everyday dancer (London, 2011), p. 120.]

Deborah Bull’s engaging and enlightening book devotes a chapter to examining the importance to ballet companies of new works. She makes the interesting point that when dance took off as a popular(ish) art form between the two world wars, there were so few pieces in the regular repertoire that, simply in order to fill out their seasons, companies were forced to commission new ballets. In fact, between 1920 and 1992 – the year when Ms Bull became a principal dancer with the Royal Ballet – there were, she suggests, an astonishing 650 of them (op. cit., p. 121). Nowadays, as a result, artistic directors enjoy what’s almost an embarras de richesses. In devising their annual schedules, they can pick and choose widely among the familiar, much-loved 19th century classics, the early-20th century legacy of Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes and its successor companies and those hundreds of more recent works.

Although the ballet repertoire can no longer be regarded as limited, newly-commissioned works still come along pretty regularly, not least for the reasons that Ms Bull mentions in her book. Most of them, it’s true, tend to be small scale, minimising any financial damage that a company will suffer if they prove to be commercial failures. However, the world’s largest companies still occasionally mount new, impressively-scaled productions. That’s partly, no doubt, because they feel an historic and moral duty to promote the ongoing development of ballet as an art form. Reasons of prestige also come into it, however, as does an element of staging a production on a large scale simply because they can. With substantial subscriber bases – and often with considerable state subsidies behind them – the biggest companies are able to take big commercial risks while minimising the danger of failure by employing the very best choreographers, dancers and musicians.

In recent years London’s Royal Ballet has boldly maintained that approach and has mounted several imaginative and substantial productions. The winter’s tale (2014) and The Dante project (2021), both based on classic works of literature, were followed in 2022 by Like water for chocolate, a newly-created large-scale ballet based on Laura Esquivel’s 1989 novel of the same name. The creative team behind the production was headed by choreographer Christopher Wheeldon and composer Joby Talbot. While clearly working with modern sensibilities, the pair have a history of producing audience-friendly works, including not only the aforementioned The winter’s tale but also the hugely successful Alice’s adventures in wonderland (2011). No horses are likely to be frightened, then, by Like water for chocolate. However, its story may not be familiar to some readers, so I will begin by offering a simplified outline of it as it’s been adapted for the Covent Garden production.

In the first Act, set during the period of the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920), we encounter the embittered and domineering Mama Elena who, years earlier, had been forced into a loveless marriage after the boy she had loved had been murdered by her own brothers. She now has three daughters, Rosaura, Gertrudis and Tita. The latter, as the youngest, is expected to follow custom by remaining single and caring for her mother. To that end, Mama Elena sabotages Tita’s hopes of marrying her childhood sweetheart Pedro and instead arranges Pedro’s marriage to Rosaura. When Mama Elena discovers that Tita and Pedro are nevertheless still in love, she sends Rosaura, Pedro and their infant son – with whom Tita has developed a close bond – away. Later, news arrives that the child has died. Shock, combined with her grief at Pedro’s continued absence, sends Tita into an emotional collapse. Under the care of the kindly Dr John, she leaves Mexico to recuperate in Texas.

In Act 2, Tita, recovering her health, receives a proposal of marriage from Dr John. Although she is not in love with him, she appreciates his kindness and becomes his fiancée. When news arrives that Mama Elena has died, the pair return to Mexico. Discovering her mother’s diary and thus the truth about Mama Elena’s own sad romantic history, Tita forgives the past unkindnesses she has suffered. Rosaura, Pedro and their second child – a daughter, Esperanza – also return to pay their respects to Mama Elena’s memory. The remaining sister, Gertrudis, who has meanwhile become the wife of a soldier in the revolutionary army, also arrives. Pedro still has feelings for Tita and the two of them manage to meet for a brief but passionate assignation, though, unknown to them, the ghost of Mama Elena herself is watching on disapprovingly. Tita – wracked with guilt and haunted by her mother’s spirit – breaks off her engagement to Dr John but, when she dances flirtatiously with Pedro, Mama Elena’s ghost appears, causing Pedro to collapse in terror

At the beginning of the third Act, Pedro is recovering his health. At the same time, however, his wife Rosaura is terminally ill. Both are nursed by Tita and Dr John who, while no longer engaged, remain good friends. Even on the verge of death, Rosaura demonstrates that she is a true daughter of the vindictive and domineering Mama Elena when she forbids her daughter Esperanza from associating with Dr John’s son Alex. However, a subsequent and final scene that takes place twenty years later depicts Esperanza and Alex’s marriage. Looking contentedly on, Tita and Pedro are magically reincarnated as their younger selves before their bodies are consumed in a fiery but peacefully serene moment of celestial transfiguration.

It’s easy to see why Wheeldon and Talbot were attracted to Ms Esquivel’s story. It’s certainly a compelling one and the life experiences of some of its characters invite us to vicariously consider important practical and moral issues. The physical and emotional interaction between those characters – whether mutually romantic (Tita/Pedro), one-sidedly would-be-romantic (Tita/Dr John and Rosaura/Pedro) or hostile and dramatically confrontational (Tita/Mama Elena and Pedro/Mama Elena) – also provides plenty of opportunities for imaginatively conceived choreography. Moreover, the story’s brightly colourful settings in Mexico and, briefly, Texas, with their inhabitants’ characteristically distinctive lifestyles, would offer any stage designer worth his or her salt plenty of chances to come up with visually vivid stagings.

However, even my necessarily simplified synopsis may have already pinpointed the biggest problem with this new ballet: its complex and rather episodic plot. The original novel had been characterised by its deployment of magical realism, a well-established literary form in which depictions of reality are closely interwoven with elements of fantasy. Wheeldon and Talbot seem to have regarded this project as something of a labour of love and so, while discarding some of the book’s more bizarre (and impossible to stage?) elements, appear to have wanted to include as much of the rest as possible in their ballet. Anyone who has read the book will no doubt appreciate and comprehend the often fleeting on-stage references to various plot points. Others, however, may simply be left somewhat bemused or even downright perplexed. Some judicious pruning, reshaping and refocusing would, I think, have done wonders in giving the ballet’s remaining material a somewhat sharper form.

Let’s consider, for instance, the character of Gertrudis, Mama Elena’s second daughter. In the book she brings home to the reader the possibility of escaping familial domination and thereby achieving a happy and fulfilled life as her own woman – something that her two sisters never accomplish. On the Covent Garden stage, however, Gertrudis simply appears, disappears, albeit quite dramatically, and then reappears. She adds little or nothing, thereby, to the ballet’s core story, while any broader significance that her character might have is an issue left pretty well unexplored. Indeed, one might reasonably end up assuming that her sole function is to precipitate a few jolly episodes to what might otherwise seem to be a rather downbeat story and, in so doing, to provide opportunities for some juicily flashy dancing – and some simulated but decidedly athletic rumpy-pumpy – that are eagerly seized upon by one of the company’s First Soloists, Meaghan Grace Hinkis.

If the ballet as such remains a somewhat problematic affair, there can be no doubt that the way in which it has been executed is an great success. As I have observed several times before on these pages, the Royal Ballet is currently going through something of a golden age. Associated with many of today’s leading choreographers, while simultaneously acting as custodian and promoter of an important historical legacy including the ballets of Ashton and MacMillan, its great strength in depth allows it to tackle an enormously wide repertoire with great confidence. Given that there really isn’t a single weak link among Like water for chocolate’s dancers, I will confine my observations to those taking the leading roles.

While it goes without saying that artists of the calibre of Francesca Hayward and Marcelino Sambé demonstrate the secure technique required to execute the choreographer’s often taxing requirements, it is notable that they also invest their performances with dramatic conviction. Ms Hayward, is a very effective actor, convincingly communicating her many moments of sorrow and despair not merely by her facial demeanour but via the smallest movements of her whole body – which are often, as is usually the case in modern choreography, of immense significance. She is on stage for a very long time and, by the end of the performance, understandably appears physically drained. Simultaneously, however, she effectively conveys an agonising sense of the mental and spiritual exhaustion that Tita has suffered because of her vindictive mother’s actions.

Mr Sambé is, by all accounts, a most engaging fellow in real life. One of nature’s cheeky chappies, the Royal Ballet has often cast him in roles requiring lots of smiles and grins. Since his 2019 promotion to Principal Dancer, however, his greater versatility has become more apparent, with acclaimed performances ranging from the tragic male lead in Romeo and Juliet to, of all things, a musical instrument. Putting his impressive technical excellence to one side, if Sambé’s acting ability in Like water for chocolate is not as immediately impressive as Ms Hayward’s, it’s only fair to point out that the role of Pedro role is not as fully developed as that of Tita and does not offer the same artistic opportunities – and, moreover, that the 60 dance critics who judged the 2023 National Dance Awards were sufficiently impressed with his work in Like water for chocolate to award him the prize for Outstanding Male Classical Performance.

As you will already know if you clicked on the previous link, Laura Morera also scooped a gong as Best Female Dancer in those same awards for her outstanding performance as Mama Elena. It’s a role necessitating the widest range of characterisations, from a lovelorn young girl to a grotesquely exaggerated ghost who sports both an enormously enveloping gown and a shock of hair that looks like it’s been blasted with 5,000 volts from an over-powered dryer. Ms Morera grabs her part by the throat from her very first entrance and, whether portraying Mama Elena as alive or dead, commands the stage – and not just her own family members – whenever she’s on it. Her retirement from the Covent Garden stage this summer leaves a gap that, in any other company less brimming with upcoming talent, would not be easy to fill.

Yet another National Dance Awards prize-winner was Bob Crowley who was recognised in the Outstanding Creative Contribution category for his Like water for chocolate set and costume designs. If you visit a UK home furnishing outlet or garden centre that sells “ethnic” garden pots and ceramics, you may well find a supposedly Mexican section and be struck by its emphasis on sometimes garishly juxtaposed, but nonetheless strikingly attractive, primary colours. That’s the sort of thing that I’d expected to encounter here but the colour palette that Mr Crowley utilises is far subtler. Maybe he thought that there was already quite enough lurid melodrama in the on-stage action without needing to exaggerate it further with an over-the-top design. In any case, both his costumes and Natasha Katz’s evocative lighting work very effectively, while the uncluttered, functional sets offer the dancers all the space they require.

Turning to Like water for chocolate’s score, Joby Talbot’s music is an appropriately fine fit for the story, both emphasising the moments of high drama and, whenever necessary, exquisitely underlining the leading characters’ despair. Working closely with the Royal Ballet company, Mr Talbot has also ensured that it also accommodates the dancers’ practical needs and recognises, in a full-length ballet such as this one, their physical limitations (an often-overlooked area that’s considered in enlightening fashion in Ms Bull’s book). There is certainly nothing here that will distress anyone who thinks that they have an allergy to contemporary music. Indeed, there are more than a few moments – including, in the final scene, a rather beautiful vocal passage sung by Siân Griffiths – where the score impresses as very attractive in its own right. Conductor Alondra de la Parra hails originally from Mexico and it would be a cheap cliché to suggest that that fact necessarily gives her an advantage in delivering the score idiomatically. Far more important is the fact that she is a very experienced conductor who, supported by the immensely versatile musicians of the Orchestra of the Royal Opera House, gets the most out of the music in a way that offers the dancers the opportunity to show themselves to best advantage.

It is also worth observing that this is another Royal Ballet production that’s been filmed by Ross MacGibbon. He is something of an unsung hero when it comes to filming dance. As someone who was himself a member of the Covent Garden company in the 1970s and 1980s, he brings to the table the knowledge and experience of an ex-dancer as well as a very keen eye. He knows exactly where to position his cameras to catch every necessary detail of a production – as well as plenty of unnecessary ones that will nevertheless add to viewers’ enlightenment and enjoyment. His expertly-crafted film has been well preserved on this DVD release and I experienced no problems with the quality of either the picture or the sound.

An area that is open to criticism, however, is the disc’s 13 minutes of filmed “extra features”, An introduction to ‘Like water for chocolate’ and Creating ‘Like water for chocolate’. Given that this is a brand-new ballet, 13 minutes’ worth of background information does seem lamentably inadequate and, while the material here is certainly useful as far as it goes, its time constraints mean that it is necessarily superficial. Things need not be that way. Stuttgart Ballet, for instance, has been adding far more substantial and illuminating extra features, sometimes 90 minutes long, to its recent releases of John Cranko’s ballets (review ~ review ~ review), something that genuinely enhances their interest and value. I do wish that the Royal Ballet and Opus Arte would follow a similar path.

Incidentally, that reference to Opus Arte reminds me to point out that in one particular respect my review is necessarily limited. I believe that most balletomanes would prefer to watch a production in its best available form – which means, in practice, as presented on a Blu-ray disc. There certainly is a Blu-ray version of Like water for chocolate – its catalogue number is OABD7312D. Unfortunately, however, Opus Arte appears to be inconsistent in its policy when it comes to offering MusicWeb reviewers Blu-ray versions of their releases and, on this occasion, one wasn’t made available. As a result, I’m unfortunately unable to assess its picture/sound quality for you or even to reassure you that the dreaded judder that once in a while affects recordings in the Blu-ray format won’t be an issue.

Even so, I’ve no doubt that this new Royal Ballet production is one that is well worth adding to any ballet-lover’s collection. It certainly offers a fine illustration of the Covent Garden company’s versatility and high standards. Moreover, it demonstrates undeniably that there’s still a place for those major new full-length productions that continue to be appreciated and valued so much, not only by Deborah Bull but also by enthusiastic live audiences in the theatre and by viewers watching at home.

Rob Maynard

Help us financially by purchasing from

Other cast

Mama Elena – Laura Moreira

Rosaura – Mayara Magri

Gertrudis – Meaghan Grace Hinkis

Dr John Brown – Matthew Ball

Nacha – Christina Arestis

Juan Alejandrez – Cesar Corrales

Don Pasqual – Gary Avis

Chencha – Isabella Gasparini

Nacha’s former lover – Harris Bell

José – Joseph Sissens

Elena’s mother – Annette Buvoli

Elena’s father – Bennet Gartside

Elena’s brothers – Tomas Mock and Kevin Emerton

Juan de la Garza – Lukas B. Brændsrød

Esperanza – Taesha Patterson and Marianna Tsembenhoi

Alex – Billy Tucker and Harrison Lee

Priest – Philip Mosley

Ranch workers – Ashley Dean, Leticia Dias, Mariko Sasaki, Ginevra Zambon, Téo Dubreuil, Benjamin Ella, Calvin Richardson and Joseph Sissens

Brides, revolutionary soldiers and wedding guests – Artists of the Royal Ballet

Other musicians

Solo guitar: Tomás Barreiro

Guest singer: Siân Griffiths

Production staff

Scenario: Christopher Wheeldon and Joby Talbot

Designer: Bob Crowley

Lighting design: Natasha Katz

Directed for the screen by Ross MacGibbon

Video details

NTSC DVD

Picture format: 16:9 anamorphic

Sound format: LPCM 2.0 and DTS Digital Surround

Region code: all regions

Subtitles for extra features: English, French, German, Japanese, Korean