Sir Charles Hubert Parry (1848-1918)

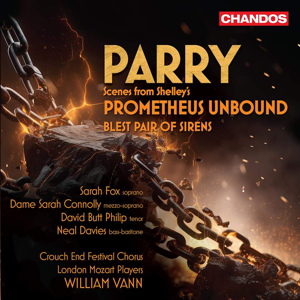

Scenes from Shelley’s ‘Prometheus Unbound’ (1880)

Blest Pair of Sirens (At a Solemn Musick) (1887)

Sarah Fox (soprano) – Spirit of the Hour

Dame Sarah Connolly (mezzo-soprano) – The Earth

David Butt Philip (tenor) – Jupiter/Mercury

Neal Davies (bass-baritone) – Prometheus

James Orford (organ), Crouch End Festival Chorus, London Mozart Players/William Vann

rec. 2022, Church of St Jude-on-the-Hill, Hampstead Garden Suburb, London, UK

Texts included

Chandos CHSA5317 SACD [70]

Parry’s dramatic cantata Scenes from Shelley’s ‘Prometheus Unbound’ was composed during 1880, the year Elgar chose in his Peyton Lectures to demarcate the beginnings of the ‘modern’ in British music. As Jeremy Dibble makes clear in his extensive booklet notes, Elgar makes no reference to a composer and it could well be that 1880 was a nice, round number but Elgar retained a strong admiration for Parry so it’s not impossible that he was thinking of this work, especially as it was premiered not in London but in Gloucester, near to his home city.

At 32 Parry was no novice. He’d recently met Wagner in London and had been immersed in The Ring, the second cycle of which he’d heard in Bayreuth in 1876. The extent to which this enthusiasm permeated his work is a pivotal one and it’s vital to hear the work in the context of the time, with the new Wagnerianism co-existing with older influences on Parry, things which would have been hard for him to fight off, such as the lingering influence of Mendelssohn, for example. However, there is something striking about Parry’s orchestral writing and his sense of musical flexibility and if his avoidance of the leitmotif may be seen as a weakness in strict Wagnerian terms – it denies the music true characterisation – it did seem to liberate him from the definitive, stylistically speaking.

Parry took scenes from Shelley’s four-act drama Prometheus Unbound (1820), a philosophical psychodrama which embodied themes that would have interested Wagner; humanity, the gods, and man’s redemption, to paraphrase Bernard Shaw. They clearly interested Parry, too, but as we have already seen in the case of Judith, his two-act oratorio of 1888, conducted for Chandos by William Vann, who directs again here, when it came to the crux of the matter – the beheading of Holofernes, in this case – Parry was too much the English Gentleman to oblige. In many important ways too, the problems I wrote about in that work, a confident orchestral introduction followed by ‘the malaise of an inheritance and a musical obligation’, though not so obvious in ‘Scenes from Shelley’s Prometheus Unbound’ are also present. At least, though, he didn’t hearken back to the Baroque as he does in Judith.

Parry selected carefully from Shelley and subdivided his work into two parts. The opening Maestoso is a short introduction that shows his deep seriousness and orchestral command but at just under three minutes reveals and anticipates a tendency to break up the music into conventional Three Choirs units of time. The declamatory Wagnerian style is clear as the work develops but as Francis Hueffer put it in a long and magnificent contemporary review in The Times – with which one can critically disagree even as one admires its insight – Parry is sometimes guilty of melodic dryness and foursquare choral setting.

Prometheus’ opening monologue, sung by Neal Davies, has a sonorous, dignified quality as well as a degree of breadth. It’s highly effective but frankly not very memorable. The figures announcing Mercury (David Butt Philip) are repeated brass calls: something of a musical commonplace, perhaps, but necessary for Parry to announce a new scene. The first chorus (of the Furies) shows Parry’s difficulty. It alternates between powerful and almost comic; or, rather, I should qualify that by saying that it may seem to us comic (it certainly does to me and it’s by no means the only time this happens with his choruses) and contextually somewhat incoherent. Yet the Voices of Spirits, toward the end of the First Part, finds him on more melodically distinguished form, mapping the chorus with unerring instinct in preparation for Sarah Connolly’s ‘Fair are others’ with which this part ends. Supported by the semi-chorus, her opulent voice is always audible.

The opening of Part II conforms to more conventional influences on Parry than Wagner and the writing for the tenor sounds a little ungrateful; certainly, Philip sounds strained, his tone hardening, turning steely. An ingeniously sepulchral chorus adds variety and colour, reflecting finely textual implications but Part II Scene I tends to wander without clarifying purpose, for all Parry’s clear skill. The soprano, here Sarah Fox, is rather underused in the work though Fox acquits herself well throughout. The Voice of Unseen Spirits opens Scene II with something very like one of Parry’s hymn settings, the roast beef quality of which gradually elides into increasingly more dramatic writing until the dreaded fugal section arrives – usually a sign of a composer applying college lessons rather than generating internal drama. The finale is rather conventional perhaps though does achieve grandeur.

Though Parry was later to be seen as a Brahmsian there aren’t too many Brahmsian gestures here – maybe, vocally, very slightly there’s a suggestion of the recent German Requiem – but otherwise his ‘Scenes’ is a perhaps uneasy accommodation between Wagnerian procedure, the need for discrete sectionality, and vestiges of Mendelssohnian choruses.

I realise that I have been rather critical of some of this work but that’s no reflection on the industry or excellence of the performers, notably William Vann. It was edited by Jeremy Dibble. Let me lastly advance the case for the defence, alluded to earlier. It was Eugene Goossens in the early to mid-1920s who told Parry’s biographer C.L. Graves that he considered it Parry’s greatest work and the greatest British work produced in the 1880s, showing features far in advance of its time. When one considers that Sterndale Bennett had only died in 1875 then the context becomes clearer, and Parry’s advances more obvious. It’s clearly an orchestrally conceived canvas in advance of other native composers at the time, including Stanford.

Talking of Stanford brings us finally to Blest Pair of Sirens, which was dedicated to him, and to the Bach Choir, in the years before he and Parry fell out. It’s been much recorded, of course, and sits here as a useful pendant. It’s ardently done but for my own tastes it’s a little on the swift side. One doesn’t have to draw it out to 12 minutes as Mathias Bamert does but a touch less vigour might have been preferable.

This is a premiere recording and the excellent booklet comes with full texts.

Jonathan Woolf

Help us financially by purchasing from