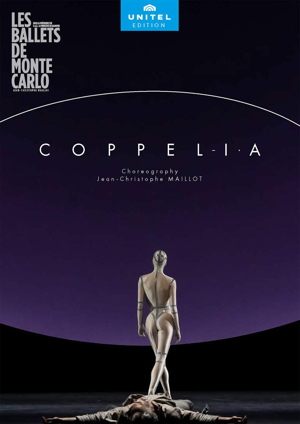

Coppél-i-A

Ballet in two Acts (1870)

Choreography by Jean-Christophe Maillot

Original music and arrangement of Léo Delibes’s score Coppélia (1870) by Bertrand Maillot

Les Ballets de Monte-Carlo

rec. 2022, Grimaldi Forum, Salle des Princes, Monte Carlo, Monaco

Unitel Edition 808708 DVD [81]

In recent years many of the familiar 19th century “classic” ballets have been given unconventional stagings. While traditionalists have often found them somewhat bizarre or even shocking, a few have gradually been accepted into the mainstream. One thinks, for instance, of Matthew Bourne’s all-male Swan lake (1995) which nowadays, at least in countries with a socially liberal sensibility, barely raises an eyebrow.

The past decade or so has seen DVD releases of a couple of front-rank dance companies’ entirely traditional versions of Léo Delibes’s Coppélia (1870). A 2018 performance from the Bolshoi Ballet was followed just a year later by one from the Royal Ballet. During the same period, however, I’ve also reviewed recordings of some smaller companies’ decidedly off-the-wall productions. First was Ballet Victor Ullate Comunidad de Madrid’s version as choreographed by Eduardo Lau in 2013, and then came a re-release of Maguy Marin’s 1993 production for Lyon National Opera Ballet. While somewhat bemused by both, I also thought them interesting experiments that were well executed and certainly worth watching. Indeed, I nominated the Madrid company’s DVD as one of my 2014 MusicWeb Recordings of the Year and, although I freely confess that my greatest love is for classical ballet in all its 19th century pomp, thereby hope that I’ve demonstrated my receptiveness to the occasional avant garde production. Let me also stress that I am generally open-minded when it comes specifically to the work of French choreographer Jean-Christophe Maillot. Indeed, I so much enjoyed the filmed version of Lac, his radically reworked version of Swan lake, that, in 2015, I chose it as one of my half-dozen Recordings of the Year.

You will no doubt have already noticed the ballet’s rather odd title. It’s actually a rather clever play on (French) words. The original 19th century Coppélia featured, you’ll recall, a life-size automaton doll as a central – if non-dancing – character. Maillot has ingeniously and topically reimagined that creature for the 21st century so that she’s now become a futuristic robot possessed of Artificial Intelligence (AI). In French, that term translates to intelligence artificielle or IA – and hence you arrive at what may perhaps be the ballet’s revised title.

My uncertainty on that point arises from the confusing documentation that accompanies this DVD release. It really is all over the place, playing fast and loose with (or without) acute accents, upper case or lower case letters, hyphens, interpuncts and single or repeated full stops. We end up, as a result, with multiple permutations and possibilities of the ballet’s title. The packaging’s front cover and page 1 of its accompanying booklet leads us to think that we’re watching Coppel-i·a (with the acute accent dropped, the second hyphen replaced by an interpunct, and a final lower-case letter “a”). Pages 4 and 5 of the booklet, on the other hand, refer to Coppél-I.A (with the acute accent restored, the lower-case “i” replaced by its upper-case equivalent, the interpunct replaced by a full stop, and a concluding upper-case letter “A”). Just to complicate matters even further, the booklet text refers to the title character by yet more variants. Coppél-i.A. – adding a second full stop after its upper-case letter “A” – appears multiple times on pages 3, 6, 7 and 8. At the same time, however, page 2 prefers Coopél-I.A which, having discarded that final full stop, adopts not only an upper-case letter “I” but also, uniquely and quite bizarrely, doubles up on the letter “o”.

While I’ve decided to use the form Coppél-i-A as it’s given on the presumably authoritative Les Ballets de Monte Carlo website, all those inconsistencies are troubling. A single variant might be a simple mistake – but so many of them? Might they, perhaps, be significant – something of a deliberate directorial attempt to discombobulate us and to subvert our expectations of what’s to come? That may sound a far-fetched idea but it is one that, oddly enough, we will encounter again in due course. Let’s park it for now and instead err on the side of caution by assuming that all we might have here is a case of some (very) careless proof-reading.

Perhaps Jean-Christophe Maillot’s revision of the Charles-Louis-Étienne Nuitter scenario, itself derived from a short story by E.T.A. Hoffmann, will explain everything more clearly? It does, it’s true, preserve certain features of the original. Several of the on-stage characters retain their familiar motivations and characteristics, though manifested in a far darker and more exaggerated form that’s appropriate to our cynical 21st century sensibilities. Dr Coppélius, for instance, is transformed here from a deluded eccentric into something of a voyeuristic “dirty old man” whose pretty indiscriminate sexual advances are variously directed at his automaton, at Swanilda and even, on occasion, at Franz. His perverted malevolence encompasses urging on his other robot creations to grope Swanilda’s friends, lasciviously stripping Coppél-i.A (or whatever her name is) of her clothes and viciously beating her up when she quite understandably objects to him using her as his sexual plaything. Meanwhile, the sequence of the on-stage action and its accompanying music has been somewhat reordered. Act 3’s wedding celebration, for instance, has been completely jettisoned, although some of its attractive music has survived to be interpolated elsewhere. Though it’s certainly true that the story’s main themes and several of its big set pieces will remain recognisably familiar to anyone who knows the ballet Coppélia in its traditional form, the changes do mean that you should certainly read the booklet synopsis carefully before watching the DVD.

Two particularly striking innovations deserve, however, a note of their own. The greatest surprise is that the story’s primary interest changes, so that instead of focusing on spunky village maid Swanilda it now concentrates on the automaton Coppél-i.A. No longer is the latter a passive doll who only moves at others’ direction. Instead, deploying that aforementioned intelligence artificielle, she becomes an active participantin the story with a real existence of her own. She possesses not only a mind but powerful sexual desires, demonstrated to the full as she explores her own body with a growing sense of wonderment and lusts after the village gigolo Frantz just as much, it appears, as he does for her. Another novelty is the introduction of a couple of entirely new characters. Swanilda’s domineering mother is a glamorously attractive woman who seizes every chance to show off a sexy pair of legs and who’d surely be yet another ripe target for Dr Coppélius’s priapic intentions. Underneath her surface flintiness, Swanilda mère, determined that Frantz will stick to his commitments and that her daughter’s nuptuals will be the highlight of the village’s social calendar, has a heart of gold. Meanwhile, readers aware that the role of Frantz was originally danced en travesti – a tradition that was maintained in Paris, at least, until the 1940s – will not necessarily be surprised that Jean-Christophe Maillot’s production accords Swanilda a newly-introduced cross-dressing companion, Lennart. While he may not add a great deal to the plot per se, his presence among the otherwise all-girl posse of Swanilda’s friends allows, quite literally, for a little heavy lifting that otherwise would be absent from the choreography.

An aspect of the ballet that one might generally expect to take for granted is the score. The DVD’s rear cover refers, however, to the “original music and arrangement of Léo Delibes’ score by Bertrand Maillot”. Bertrand is choreographer Jean-Christophe’s brother and you will have noted – whether with piqued curiosity or a looming sense of foreboding – that the quoted billing prioritises his original music over the elements of rearranged Delibes. Bernd Wladika’s booklet essay gives a good indication of what to expect. He refers to the score’s “ultra-modern character [achieved] by the use of electronic sound sources” and it is certainly true that no real-life orchestra is credited anywhere in this production’s documentation, even though you’d find that hard to believe that when listening to the soundtrack itself. With the booklet essay going on to quote Dance for you magazine’s assessment that Bertrand Maillot’s deployment of “virtual” (i.e. computer-generated) instruments and vocal effects allows the music “to take a leap into the future”, MusicWeb’s more traditionalist readers may already be preparing a panicky leap back into the past. I would urge them, however, to hesitate a few moments longer before doing so.

It takes, in fact, only a moment or two to discover that in this particular case, “a [musical] leap into the future” means more of a relatively modest step that really needn’t cause too much concern at all. There are, in fact, long stretches where we hear the score and orchestration just as Delibes intended it – and when Bertrand Maillot’s “arrangements” do come into play, they are, while certainly striking, nothing out of today’s mainstream. The ballet’s opening few moments, now allocated the title Prologue: the birth of Coppél-i-A., demonstrate something of his approach pretty well, with recognisable phrases from Delibes’s familiar prelude and mazurka juxtaposed and sometimes almost overwhelmed by various unexpected harmonies and discordantly unsettling sounds from both a solo piano and a full, but presumably “virtual”, orchestra. If the score is occasionally delivered in a manner so ear-splittingly strident that it’s reminiscent of the 1970s Portsmouth Sinfonia, I think that we can at least assume on this occasion that any orchestral dissonance is deliberate. As I tentatively suggested earlier, perhaps one of this production’s intentions is to discombobulate a conservative ballet audienceout of its comfort zone – while, obviously, not going so far as to discombobulate them entirely out of the theatre. If that’s the case, the intermittent deployment of those weird (dis)harmonies and unexpected re-orchestrations is certainly an effective means of doing so, as, indeed, are the occasional passages – some of them quite lyrical and attractive – that have been composed by Bertrand Maillot with no reference to Delibes at all.

As is often the case with modern ballet, choreography is not necessarily something that is easy to describe in words or, especially, to assess. Classical ballet – which was the dominant form until the advent of Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes just before the First World War – prioritised grace and elegance in movement and generally prized visual uniformity and symmetry in the deployment of dancers on stage. Choreographers such as Petipa or Bournonville employed standardised physical – and, indeed, verbal – vocabularies that are still familiar and used today and which offer, therefore, universally recognised definitions and yardsticks with which to judge any “traditional” performance. Many modern choreographers have, on the other hand, sought to make ballet more “relevant” to audiences by adopting styles that reflect the predominant characteristics of contemporary life. Their dance styles have frequently, therefore, emphasised unpredictability, instability, tentativeness and often fierceness in movement, as well as putting greater emphasis on dancers’ unconformity and individuality. Meanwhile, individual choreographers’ characteristic and sometimes unique dance vocabularies no longer facilitate critical judgments based on commonly accepted standards – to the extent that it is sometimes difficult to distinguish a choreographed move from a dancer’s outright error. In such circumstances, very often the best that one can do is to assess whether the music and choreography are good fits – not that they must necessarily gel harmoniously in style but that each adds something to the other and that the whole artistic creation thereby emerges as more than the sum of its individual parts.

In this particular production, Jean-Christophe Maillot’s choreography turns out to be an engagingly eclectic mixture of differing elements. While some are strikingly modernistic, others are relatively conservative and familiar. All, however, are carefully crafted and aligned so as to create rounded and believable impressions of the ballet’s characters. Some of the latter, including the automaton and Swanilda’s hyper-energetic mother, are generally characterised by angular, jerky movements that are reflective of their spiky, difficult or abrasive personalities (and even a robot possesses one, it seems, as, in dealing with her creator, Coppél-i-A displays all the sensitivity of a bolshie, fully paid-up member of the awkward squad). The choreography for some of the other characters, notably Swanilda and Frantz, often tends to be lyrically romantic and more influenced by ballet tradition. Whichever the case, there is a consistently successful degree of integration between styles of dance and the remodelled musical score.

That fine partnership of the Maillot brothers’ choreography and music offers the Les Ballets de Monte-Carlo dancers some tremendous opportunities to impress us on the spacious, uncluttered stage. Smoothly – and seemingly effortlessly – transitioning between spiky, modernistic passages and others reflecting an older ballet tradition, they demonstrate not just their technical skill but their artistic versatility. I enjoyed the performances of all of them, but must give special recognition to Matěj Urban (Dr Coppélius), Mimoza Koike (Swanilda’s mother) and Lou Beyne (Coppél-i.A). What’s interesting, of course, is that all three take on new or newly-expanded roles, and each of them dominates the stage whenever they’re on it. In comparison, poor Swanilda and Franz, fine dancers though Anna Blackwell and Simone Tribuna undoubtedly are, don’t have much of a chance when it comes to grabbing our attention from them.

Designers’ choices regarding the use of colour, tone and lighting can be quite significant in productions of Coppélia, for, as I have pointed out on earlier occasions, it is, at the very least, a morally problematic tale that has a definitely dark side to it. Dr Coppélius himself, let’s remember, is not the only character who can be accused of cruelty or even outright sadism: the way that Swanilda humiliates him for his doddery eccentricity in the original version is to modern sensibilities, at least equally reprehensible. Different companies tackle that aspect of the story in different ways. The current Bolshoi production chooses to ignore it entirely, with the brightly lit, primary-coloured Act 3 wedding celebrations implying that all difficulties have been cloudlessly resolved and that Swanilda’s future will be spectacularly happy. The Royal Ballet, on the other hand, chooses predominantly dark blue hues at that point, playing down the joy and hinting, perhaps, that Swanilda’s union with the randily promiscuous Frantz will not necessarily be a bed of roses after all. In similar fashion, Maillot’s production is based on a limited but rather beautiful colour palette of dusky blues and greens, purples, whites, silvers and greys – all cool, emotionally restrained colours that constantly, albeit subconsciously, remind us of his refocused story’s chilly and decidedly cruel heart. The absence of vibrant colour is further emphasised by Aimée Moreni’s almost completely bare set and her simple plain white costume designs, the general ubiquity of which only serves to stress the individuality of the two disruptive “outsiders” who wear something a little racier – Swanilda’s mother, whose dress is unique in showing off the full length of her legs, and the automaton who sometimes sports a cleverly effective “nude” outfit.

It’s possible to miss another of the design’s themes if you’re not looking out for it. The 19th century ballet’s full title was Coppélia, or the girl with the enamel eyes and that, perhaps, is the explanation of a particular preoccupation with eyes that seems to run through this production. The whole story is, of course, centred to a large extent on the idea that people do not necessarily see the truth but instead only see what they want to. Most obviously, Frantz “sees” the automaton as flesh-and-blood and Swanilda “sees” that Frantz loves her. Once you notice that the large round gap at the back of the stage is constantly changing its size and shape, like the iris of an all-seeing eye, and then spot that Coppél-i-A herself never blinks until she is finally humanised, you’ll begin to see similar motifs popping up elsewhere too. At one point, Lennart playfully jokes about poking out Swanilda’s eyes – and, later on, the automaton will actually kill Dr Coppélius in that very same way. I’ve even begun to suspect that that weird form of the title that we noted earlier – Coopél-I.A – might conceal a Da Vinci code-type hidden meaning, with the “oo” actually a coded pictorial reference to those enamel eyes. But perhaps, as King Lear pointed out, that way madness lies…

As a product, the DVD itself is of pretty good quality. The sound is excellent but there are a few instances of motion blur, with the most obvious episode occurring during the ballet’s familiar final galop or, as it’s billed here, And finally they got married. While the booklet is informative and, indeed, as already noted, an essential aid to comprehension, the absence of even a single extra feature on the disc is a missed opportunity. Another one – and I make no apologies whatsoever for hammering home this point once again – is the distributor’s failure to offer a Blu-ray version for review. This is surely a release aimed not primarily at generalists but at specialist balletomane collectors and, if it appeals to them, they will want to acquire it in the best quality format, i.e. as a Blu-ray disc. Once again, however, I find myself unable to vouch for the quality of such a release and I can only apologise to MusicWeb readers for that fact.

Based solely on the DVD release, however, I consider that this newly remodelled variant on Coppélia trumps both the Madrid and Lyon versions that I referenced earlier. It is clever, slick, very accessible and often rather beautiful beautiful to look at. While you ought certainly to own and familiarise yourself with a conventional 19th century style Coppélia before you consider buying this one, it would certainly make an intriguing and enlightening second choice. It also taps into the contemporary Zeitgeist in suggesting that all the warnings we’re currently hearing about the threat to mankind’s future posed by the rise of Artificial Intelligence may be true. Now, thanks to Jean-Christophe Maillot’s imaginative new ballet, we can no longer say that we haven’t been warned…

Rob Maynard

Help us financially by purchasing from

Cast

Coppél-i.A – Lou Beyne

Coppélius – Matěj Urban

Swanilda – Anna Blackwell

Frantz – Simone Tribuna

Swanilda’s mother – Mimoza Koike

Lennart – Lennart Radtke

Swanilda’s friends – Gaëlle Riou, Kaori Tajima, Hannah Wilcox and Anissa Bruley

Frantz’s friends – Adam Reist, Daniele Delvecchio, Michaël Grünecker, Koen Havenith and Benjamin Stone

The prompts – Kathrin Schrader, Francesco Resch, Chelsea Adomaitis, Cristian Assis, Juliette Klein, Lydia Wellington, Jaat Benoot and Ashley Krauhaus

Prototypes – Benjamin Stone, Koen Havenith, Christian Tworzyanski, Cristian Oliveri, Alessio Scognamiglio and Jaat Benoot

Production staff

Dramaturgy: Geoffroy Staquet and Jean-Christophe Maillot

Set and costumes: Aimée Moreni

Lighting design: Samuel Thery and Jean-Christophe Maillot

Video director: Louise Narboni

Video details

DVD mastered from an HD source

Picture format: NTSC 16:9

Sound format: PCM stereo and DTS 5.1

Region code: 0