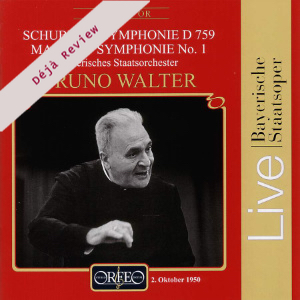

Déjà Review: this review was first published in August 2002 and the recording is still available.

Franz Schubert (1797-1828)

Symphony No.8 “Unfinished” D759

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911)

Symphony No.1 in D minor

Bavarian State Orchestra/Bruno Walter

rec. live, 2 October 1950, Kongresssaal des Deutsches Museums in Munich

Orfeo C562021B [73]

Bruno Walter made his first post-war appearances in Europe between 1947 and 1949 but he didn’t venture into Germany until 1950 when he conducted in Berlin and Munich. One concert from each city was recorded for radio broadcast and these have now appeared on CD for the first time on two different labels. The Munich concert is on this issue from Orfeo whilst the Berlin concert (Mozart’s 40th and Brahms’s 2nd with the Berlin Philharmonic) is on Tahra (TAH 452 – review). In fact, as the poster for the concert shows, the Munich concert also contained Weber’s Euryanthe Overture but issuing that would have meant spilling on to a second CD so the decision has clearly been taken to leave that in the archives.

Walter had worked for ten years in Munich between 1913 and 1922 so it must have been a shattering experience to be led (by the young Georg Solti) through the ruins of the bombed National Theatre to the rehearsal hall at the side of the gutted building when he arrived. I don’t think I’m being too fanciful in hearing some of that regret in his fine, old-world reading of Schubert’s “Unfinished” Symphony. The second movement in particular is grave and solemn, full of nostalgia and yearning and a real tone of memoriam. Likewise in the first movement Walter moulds the melodic line with love and care, but then when the time comes he can thrust home the symphonic argument memorably. It was only in his later years Walter gained the reputation of “soft grained” and here there is power and resolve when the velvet glove comes off.

The Mahler First is similar in conception to Walter’s first studio recording, the one he made with the New York Philharmonic a few years after this Munich performance. It is swifter and more closely argued than his final recording, made in stereo in California, but still maintains the lilt and the lyricism of the Schubert performance where appropriate. The introduction to the first movement manages to be lyrical without being ponderous. Indeed Walter’s unwillingness to drag is a reminder that this was the era of quicker Mahler tempi. So the first subject theme, from the second of the “Wayfarer” songs, moves with a real spring in its step. In the development that follows I was quite surprised at how little portamenti Walter asks of his cellos and how well the soft pulse of the bass drum is reproduced in this limited broadcast tape. I also enjoyed Walter’s innate grasp of string phrasing following the quiet announcement of the clinching theme from the horns. At the real climax of the movement the recording betrays its origins in that the full tutti gets rather crowded on the ear, but if you are prepared to listen through this you will enjoy the sweep of the music to the timpani punctuation at the end.

The second movement seems to catch the orchestra off guard, as there is some insecurity in the ensemble. I also think Walter’s breezy treatment of the trio section a little unidiomatic. The opening of the third movement is marred somewhat by creaks and shuffles on the platform and from coughs from the audience but on the plus side is a reedy double bass soloist, a bassoonist full of character and a really lugubrious tuba player all caught well by the microphones. The “café band” interjections are slightly held back which makes a good ironic point and the central core of the movement, another “Wayfarer” quote, is chaste and gently etched and note too the slides from the violin solo.

The limited sound does mar the opening of the last movement, as does the hard edge of the orchestra. However so much is made up for by Walter’s intimate knowledge of the music in the movement – the peaks and troughs of Mahler’s first finale – to allow him to deliver the full gamut of emotion: excitement, nobility, longing and, in the passage before the coda, nostalgia again. The orchestra keeps up most of the time too. Even though Mahler could hardly have been familiar fare to a German orchestra in 1950. This was five years after many years of Nazi banning had finally ended, remember. Walter delivers the coda with panache but also with a trenchant, heavy downforce on the rhythm.

The mono broadcast sound in both works is clear and yields a surprising amount of detail. However, as you would expect, the dynamic range is quite narrow and there’s a top edge and a glare in both the louder passages and the higher frequencies, as well as deficiency in the bass. There are also the coughs and shuffles of the audience to take into account and some platform mishaps.

I would never recommend recordings like this as first choices. Neither would I normally compare them with modern versions. Issues like these are principally of value for their historical interest and any musical value stems from that. But to hear Schubert and Mahler conducted by this man at this time on this occasion is something which should interest those who, like me, believe musical performances are events set in time. From this time in particular I believe there is that tone of regret in the Schubert and I also thought the very subdued applause at the end of the Mahler instructive when compared with the greeting they gave to the Schubert. Five years before this performance the members of this audience were still being told that this music was “Jewish trash” not fit for their ears, and so they must have felt a mixture of emotions when listening to it and when reacting to it.

As a piece of history in sound I found these performances fascinating and very enjoyable.

Tony Duggan

Help us financially by purchasing from