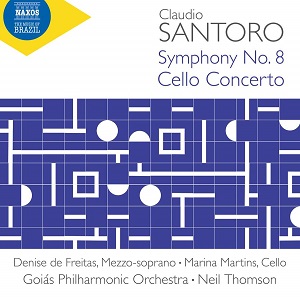

Claudio Santoro (1919-1989)

Cello Concerto (1961)

Symphony No 8 (1963)

Três Abstrações (1966)

Interações Assintóticas (1969)

One Minute Play (1966/1967)

Marina Martins (cello), Denise de Freitas (mezzo-soprano)

Goiás Philharmonic Orchestra/Neil Thomson

rec. 2018-22, Centro Cultural Oscar Niemeyer, Goiânia, Brazil

Naxos 8.574410 [66]

In the 1960’s, Claudio Santoro spent some time in Europe, including England. His musical outlook, now considerably broader, became largely cosmopolitan. His travels brought him in contact with European composers and musical institutions. That allowed him to explore new musical grounds. Some of these new acquisitions are clearly to be heard in the works composed in what may be roughly regarded as his German decade.

Santoro was in East Berlin when the construction of the Berlin Wall began. That was when he composed his substantial Cello Concerto, a big piece in three weighty movements. The first movement – more than half the whole duration – begins with a long, dark, ominous introduction. In effect, the soloist’s first entry almost passes unnoticed, as the instrument is primus interpares. Soon enough, the cello’s part becomes more intense and strongly expressive. It builds up to a cadenza, and then clearly assumes its role as important protagonist. The Lento second movement is rather bleak and desolate, but the third movement seems to redress the balance. Gustavo de Sá writes in the booklet notes: “The third movement is the most characteristically concertante of three.” The music is overtly tense and animated, but it never clearly expresses triumph or relief of any sort.

Gustavo de Sá rightly remarks that the Cello Concerto may not be a programmatic work but it is impossible to dissociate its charged atmosphere from contemporary events in Berlin. I firmly believe that composers often reserve their deepest thoughts and feelings for their cello concerti. This is no exception, a sombre, tense, strongly expressive piece that should be heard more often. Marina Martins plays beautifully, with commitment and conviction. This is a major work by any counts.

The Symphony No 8 was completed when Santoro had been invited to become head of the music department of the newly established University of Brasilia. Due to academic responsibilities, he composed relatively little. The exceptions are the Sonata No 4 for Cello and Piano, and this Symphony. This rather short and compact work in three movements offers strongly contrasted moods. Musically, it may be noted that the writing and the overall sound picture of the work tend towards a kind of Expressionism. This is particularly clear in the outbursts heard in the first and third movement. The central Andante unfolds a dark threnody scored for wordless mezzo-soprano and orchestra. Compared to the strongly expressive Cello Concerto, the Symphony sounds sparse and ascetic, though not without drama. Another mighty yet somewhat understated piece that needs repeated hearings to make its points.

The various works recorded here all date from the decade when Santoro explored various musical issues; he obviously came in contact with trends new to him. It is important to note, however, that none of the works here is in any way experimental. He assimilated a number of techniques, such as aleatoricism, and achieved something completely personal. This is particularly noticeable in Três Abstrações (three abstractions) for strings and Interações Assintóticas (asymptotic interactions) for orchestra. The former is a set of shorts studies in string writing. The first movement relies almost entirely on orchestral timbres in the form of stasis and glissando clusters. In the second movement, the strings are mainly reserved to solo interventions from the section leaders. The third movement may sound rather more conventional, but the writing is “notable for its unstable rhythm and brusque violent chords”. This short but quite taxing piece should appeal to any enterprising string ensemble.

The title Interações Assintóticas has mathematical connotations, but the important characteristic of this superb piece of music is the imaginative and inventive writing for orchestra. About half the orchestra is tuned a quarter-tone lower, and that is meant to create some sort of musical asymptote. The composer displays his mastery of aleatory writing while eschewing any formal chaos: everything is still strictly controlled by his will. (One may compare this to Lutosławski’s controlled aleatoric writing.) The music is assured and the piece unfolds to a mighty earth-shaking percussion tattoo. I am in no doubt about it: this is one of the finest pieces here next to the Cello Concerto and Symphony No 8.

This fine release closes with One Minute Play. It is a short, exhilarating piece for strings meant as an encore, and has demanding string writing for its brevity. It really plays for a little over one minute.

This third release in Naxos’s Santoro cycle is most welcome indeed. One must single out the magnificent Cello Concerto, the dramatic if somewhat understated Eighth Symphony (with a wordless voice part beautifully sung by Denise de Freitas), and Interações Assintóticas, especially in such committed readings. These powerful and strongly articulated pieces considerably add to one’s appraisal of Santoro’s musical progress.

Hubert Culot

Help us financially by purchasing from