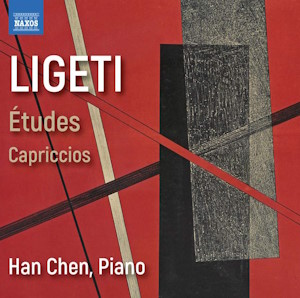

György Ligeti (1923-2006)

Études Books 1-3

Capriccios

Étude No. 14 (First version)

Han Chen (piano)

rec. 2022, Oktaven Audio, Mount Vernon, New York

Naxos 8.574397 [62]

It is rather wonderful how readily Ligeti’s very demanding piano Études, which were written between 1985 and 2001, have been accepted as classics of the piano repertoire. There are now at least half a dozen complete recordings, plus versions of a few of them separately in mixed recitals. This latest issue is the third I have reviewed for MWI and my colleagues here have reviewed several others.

Ligeti wrote a fair amount of piano music in his youth, but, after he left Hungary, he first concentrated on the orchestral and choral works which made him famous. I believe that during this time he did not have a piano of his own. When he was able to acquire one, he started writing these Études which, he said were motivated by his own inadequate piano technique. He could not, in fact, play them himself. Indeed, a mere look at the pages is enough to make the average amateur pianist gasp and blench. In writing them he was influenced, partly by the Études of Chopin, Liszt, Debussy and Bartók, but also by the polyrhythmic player-piano studies of Conlon Nancarrow, unplayable by human beings, and also by music outside the Western classical tradition such as jazz and African drumming. He often uses irregular rhythms, with bar lines only serving to help synchronise the hands, devices such as one hand playing only on white notes and the other only on black, anomalous key signatures, rhythmic complications of all kinds, extremes of volume and in using the top and bottom of the keyboard and in floating a long, strange melody over a turbulent underlying texture. Ligeti originally intended to write only twelve Études, a traditional number for such works, but enjoyed composing them so much that in fact he wrote eighteen and would have written more had illness not prevented him. He gave them all poetic titles, in various languages.

But these pieces are not just clever, complicated and hard to play: they are also very attractive, witty and beautiful. No wonder pianists who can get their hands round the notes like to play them. So now we can introduce their latest exponent, Han Chen, who has already a number of recordings to his name, including one of the piano music of Thomas Adès which I found quite interesting (review). He plays these pieces rather as I imagine Yvonne Loriod might have done, though I don’t know that she ever did. His playing is remarkable for its accuracy and brilliance and his style emphasizes their modernist characteristics, rather underplaying their witty and poetic aspects. So, he is excellent in the fast and furious ones, such as the opening Désordre, bringing out the bell-like motif about the churning figures beneath, Touches bloquées interweaving two different rhythmic patterns at tremendous speed or Der Zauberlehrling which has racing triplets with irregular accents. However, the few slow numbers, such as Arc-en-ciel or En Suspens are rather matter of fact. I also feel he somewhat misses the wit in those pieces which are successors to Bartók’s Dances in Bulgarian Rhythm (from Mikrokosmos), namely Fanfares and Fém. And in what I think is the finest of them all musically, Automne à Varsovie, based on a falling figure at overlapping different speeds, I didn’t feel the tragic quality which I have found in some other versions.

However, Han Chen has more to offer. In addition to the eighteen Études he offers us three other works. Two are early, the Caprices which Ligeti wrote in the 1940s. They are both attractive pieces and in them I fancy I could hear in embryo some of the techniques which came to flower later. And finally, he gives us the original version of Étude 14, Columna infinită, titled Coloana fara sfârşit. When Ligeti wrote this he decided it was unplayable by a human pianist: it consists of thick chords in constantly rising waves marked Presto possibile, tempestuoso con fuoco. Ligeti decided this would have to be realized by a player piano; this has been done and you can find it on the internet. Chen manages to play it, though admittedly at a rather slower tempo than the composer wanted; however, the player-piano version lacks that element of strain and effort overcome which, as in works such as the Hammerklavier Sonata or Liszt’s Sonata, is actually an essential aspect of the composition.

As I mentioned, there are several other recordings of these fascinating works. The reference version is that by Aimard, but this is inconveniently split over two discs from two different companies, Sony and Teldec. This was because Aimard recorded the first fifteen before Ligeti wrote the last three and by then the lead in recording Ligeti had shifted. I particularly liked Danny Driver (review) though Dan Morgan had reservations (review). Thomas Hell and Fredrik Ullén (review) are also worth considering. But Chen also comes into the picture and his extra items are worth having, particularly at the Naxos price. It is very reassuring for those of us who care for contemporary music that Ligeti’s Études have caught on so well.

Stephen Barber

Help us financially by purchasing from