Bernard Herrmann (1911-1975)

Suite from Wuthering Heights (1943-1951 as adapted by Hans Sørensen in 2011)

Echoes for String Quartet (arr. Hans Sørensen for string orchestra) (1965, arr. 2011)

Keri Fuge (soprano – Cathy), Roderick Williams (baritone – Heathcliff)

Singapore Symphony Orchestra/Mario Venzago, Joshua Tan

rec. 2020-22, Esplanade Concert Hall, Singapore

Chandos CHSA5337 SACD [80]

This is an intriguing and very enjoyable recording on several levels. Any new disc of music by Bernard Herrmann is to be welcomed all the more so if it contains “new” music. In this instance an extended suite running to 60:13 taken from Herrmann’s magnum opus, the opera Wuthering Heights, alongside a string orchestra version of Herrmann’s only quartet Echoes. The playing is entrusted to the Singapore Symphony Orchestra making what I think is their debut recording on Chandos. Previously the orchestra has produced many superb recordings for BIS so it will come as no surprise that the playing is excellent and the recording in the orchestra’s famed Esplanade Concert Hall is spectacular in SA-CD multi-channel sound (I listened to the SA-CD stereo layer). The production and sound engineering team are a Singapore-based company with Chandos’ Ralph Couzens acting as executive producer. Conductor Mario Venzago – most familiar to collectors for his controversial Bruckner cycle on CPO – might not appear at first glance the most likely conductor but again his contribution cannot be faulted.

However, taken all together it does seem a slightly improbable combination of artists and location for this opera by an American set on the Yorkshire Moors. Dig a little deeper and I think an explanation comes clear. The skilled adaptation of both works is by another unfamiliar name Hans Sørensen. Sørensen is the current Director of Artistic Planning for the Singapore SO. Back in 2011 – when he prepared this suite – he was Artistic planner for the Danish National Symphony Orchestra. 2011 was the last time Chandos recorded any Herrmann – a stunning version of his cantata Moby Dick – with surprise surprise the Danish National SO. So my guess is that there was a plan for a second Herrmann disc with those forces as part of his centenary celebrations which for whatever reason never came to fruition until now. The Singapore orchestra gave the premiere concert performance of this work in May 2022 alongside the recording sessions – with Beethoven’s Symphony No.5 in the first half. I am genuinely glad for Sørensen (and Herrmann!) that all his hard work of twelve years ago finally gets heard because the result is musically very impressive and wholly enjoyable.

The genesis of the opera is quite well known and tortuous. Herrmann produced a score for a film adaptation of Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre in 1944. As part of that process he immersed himself in the world of the Brontës from which sprang a wish to write an opera based on Wuthering Heights. It took him eight years working around film commissions and other commitments to complete the work to a libretto by his then-wife Lucille Fletcher. He spent most of the rest of his life trying to persuade anyone to stage or at least take an interest in this work which he knew contained the best of him. He eventually funded a complete recording – which he also conducted – for Pye Records in London in 1966. At the time of its release on 4 LP’s the reception was at best muted which was probably due to Pye’s limited release schedule and advertising budget. The subsequent appearance on CD by Unicorn allowed listeners to appreciate the work in full and that recording – out of print and not cheap to find – still sounds very good for its age. The full opera was not fully performed on stage until 2011.

The issue for those seeking to dramatically adapt the original novel is its unusual structure and convoluted form. Herrmann/Fletcher’s solution was to excise most of the latter part of the story from after the death of Cathy. As a website devoted to the novel here points out the complete novel is really a story about Heathcliff’s revenge. What all the adaptations tended to focus on – and Herrmann did too – is the doomed love of Cathy and Heathcliff. So if the complete opera is a fairly major condensing of the novel then Sørensen’s suite is a further condensing of that condensing. Sørensen retains just two voices; here soprano Keri Fuge singing Cathy and Roderick Williams singing Heathcliff which further focuses the music and the listener onto their relationship alone. The good news is that both Fuge and Williams are excellent in their roles. Vocally they are well matched and sound beautiful when singing together or in solo and the recording has caught their voices truthfully and balanced them ideally in the often rich orchestral textures Herrmann writes. Likewise Venzago draws a wonderfully wide and expressive range of instrumental colour from the orchestra. Part of the “problem” I am sure Herrmann had selling the concept of this opera in the 1950’s and 60’s was that in spirit and indeed musical execution it is in the tradition of Romantic Opera. Although Herrmann deploys a large orchestra it is a pretty traditional one. In his film scores he was renowned for utilising any number of bizarre and original instruments to obtain specific effects. In the Brave New World of post-war modernism I can imagine this score in terms of both the music and the dramaturgy presenting as too old-fashioned. From the stand-point of 2023 it can be appreciated for its many beauties and sophistication.

Sørensen retains the narrative arc of the original work starting with an excerpt from the Prologue where the distraught Heathcliff calls to the ghost of Cathy through a raging storm, to their burgeoning love, Cathy’s final illness and death to Heathcliff’s remorse and a return to the despair of the Prologue. For those who know Herrmann’s other work – both cinematic and concert – there are numerous fingerprints of his sound, melodic shape and harmony. In some instances this is because he literally used themes he had written for earlier films. The Wikipedia article on the opera cites four examples/films but it has to be said they are passing and also exploited for their musical potential rather than repeating their original cinematic/dramatic context. Perhaps more interesting for the listener are the musical influences. Some have noted a Puccianian sweep and ardour to the writing which is undoubtedly true but I think that is more a question of the context and the use of a similar instrumental and harmonic palette. My reaction to this work – especially in the excerpts from Act I (tracks 2-7) when the relationship between Cathy and Heathcliff is at its most passionately benign – is the influence of Delius. There is a sense of emotional and musical rapture that if not mimicking the older composer certainly shares a similar emotional landscape to great and good effect. For me this is the sequence that is overall most effective simply because it is the most complete and near-sequential to the original.

Sørensen has to balance making not just the musical elements satisfyingly contiguous (which he succeeds in doing admirably) but also creating enough way-points in the dramatic narrative that give the listener unfamiliar with the complete opera, let alone the novel, a clear sense of the unfolding story. Perhaps here he is stymied by the sheer scale of the original. Herrmann’s 1966 recording last around 186 minutes – here we have 60. Over the years operas have been sourced for either orchestral suites or sequences or of course “bleeding chunks” excerpted from complete recordings. This creation of a hybrid dramatic reduction is very unusual – possibly Delius’ Idyll which he himself reworked from a version of Margot Le Rouge is one of the few other examples I can immediately think of. That Sørensen succeeds as well as he does is great credit to himself as well as the performers and probably the best way to approach the work is not as a kind of operatic digest but a standalone work based on the opera. Sørensen omits all of the Act III music and in fact only includes one (beautiful) excerpt from Act II sung by Cathy; “I have dreamt in my life.” This aria is the one that has had a life away from the opera appearing on recordings by Renée Fleming and Kate Royal. So the drama jumps pretty much straight from the love scene on the moors to Cathy’s deathbed – she is dying from the consequences of childbirth although nothing in this suite’s libretto makes you realise the child is not Heathcliff’s. Again Fuge and Williams handle their quite different interaction with great musicality and dramatic power. There is a feverish energy that is very well conveyed. The closing sequence where the tormented Heathcliff hears the disembodied voice of Cathy calling out to him through the storm does feel rather too quickly arrived at – again in the novel this building anguish takes place over years. But that is a flaw in the opera not this adaptation – there are barely twenty minutes of music from Cathy’s final entrance to the closing curtain in the complete work, This suite includes much of this sequence including the brooding Meditation that precedes it. One tiny production choice – when the voice of Cathy calls from afar the chilling “Heathcliff! Heathcliff! Let Me In…” for all that Keri Fuge sings beautifully she is very ‘present’. On Herrmann’s recording the voice is distant and rather etiolated and a wind sound effect has been added. Those might both be rather obvious choices but they do send a chill down the spine in a way not achieved here. Although the old recording is tricky to find there is another complete version available on CD which is a record of a complete concert performance from the Festival de Radio-France-Monpellier, made in July 2010. However, that appears to be just as hard to track down so I can imagine listeners enjoying this new disc but then being frustrated when trying to hear the complete work. The French performance can be heard complete on YouTube here but although good the singers here are better.

The coupling as mentioned is Sørensen’s adaptation also in 2011 of Herrmann’s string quartet Echoes. The original work – which plays continuously for around 20 minutes – has been recorded several times before and it is very effective in its original form. The very good liner note by David Benedict (which includes the brilliantly concise description; “Herrmann was cinema’s master of anxiety”) points to the fact that this piece of absolute music allowed Herrmann to write free of the demands and constraints of a dramatic film score. So it could be argued that although there is no story or narrative to the piece the mood of brooding melancholy and nostalgia is a true reflection of the composer himself. Again the Singapore SO players acquit themselves superbly and conductor Joshua Tan taps into the vein of sorrowing loss that echoes (pardon the pun) a spirit common to the later non-film scores of Korngold. For sure using a very different musical vocabulary but sharing similar emotional goals. Again Herrmann mines his extensive back catalogue of cinematic themes – here using material from Vertigo and The Snows of Kilimanjaro. Benedict also suggests “the creeping unease of Psycho” elsewhere in the work. He also writes that the score is “emotionally enriched by the increased body of sound”. I do not hear the improvement in quite such definitive terms. Certainly this is a work that deserves to be wider known both by audiences and players so I would hope that this new edition allows that to happen. As a work it finds an effective balance between the true individual compositional voice of Herrmann and his cinematic incarnation.

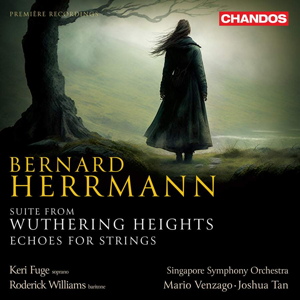

If indeed this is part of the Centenary Celebrations – albeit twelve years late – it has been worth the wait and I cannot imagine more compelling performances. This new suite provides an excellent introduction to the dark and ultimately desperate world of Wuthering Heights although by its nature it must surely act as a gateway to the complete work for the inquisitive listener. Chandos’ usual high production values are in evidence throughout with demonstration quality SA-CD sound revealing the detail and range of Herrmann’s writing. One last little detail – the rather moody but effective illustration that adorns the liner booklet and has been printed on the disc is the creation of an AI programme “with the assistance of Andy Brooks”. I probably show my age by finding that both impressive but faintly disturbing at the same time – much like Herrmann’s music.

Nick Barnard

Previous reviews: Rob Barnett (July 2023) ~ Paul Corfield Godfrey (July 2023)

Help us financially by purchasing from