George Antheil (1900-1959)

Violin Sonata No.1 (1923)

Violin Sonata No.2 (1923)

Violin Sonata No.3 (1924)

Violin Sonata No.4 (1947-48)

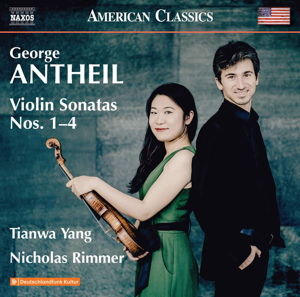

Tianwa Yang (violin), Nicholas Rimmer (piano, drums)

rec. 2021, Saal 3, Haus des Rundfunks, Berlin, Germany

Naxos 8.559937 [69]

I was determined not to write “bad boy of music” in this review. After all, it is the label that is almost always associated with George Antheil, and as such feels like a rather lazy comment to use – after all what does it actually mean? But then you realise that Antheil himself chose that as the title of his autobiography and it was an image – you feel he would have done very well in the modern social media focussed world – that has endured way beyond any wider knowledge or understanding of the actual music he wrote.

Gaining that wider knowledge is where this impressive new disc from the ever-excellent violinist Tianwa Yang and her long-time piano colleague Nicholas Rimmer comes in. In Frank k. DeWald’s informative liner he notes Antheil’s stated intention to become “noted and notorious… as a new ultramodern pianist composer”. Those intentions disturb slightly – no wish to be well-regarded or popular or even to write music that was deeply felt or personal. Antheil’s choice of phrase implies someone more intent on becoming a controversial celebrity where music is merely the means to the end rather than the driving imperative. I had not heard these four sonatas before. The catalogue offers alternative versions but I would be impressed if those can match this new version for the sheer virtuosic address and technical élan of Yang and Rimmer. The actual playing is genuinely spectacular making light of both the complexity of the writing and the frenetic almost schizoid manner in which it often flits between styles and musical material within a bar or two. Antheil is by no means the first or last composer to use a kind of montage effect in his writing. My main observation here is whether it truly serves his musical goals or is simply a way of shocking his audience. The influences are explicit and certainly in the Sonata No.1 fairly undigested. In the midst of all the shock-montage writing, Stravinsky looms large. Again, it is a tricky judgement call to decide where influence ends and imitation begins.

Perhaps because I do not find myself responding that warmly to Antheil’s writing I feel I hear more imitation than influence as though he has absorbed the manner and musical gesture of the senior composer and can reproduce it as a pastiche. Of course the other “daring” stylistic influence is “the jazz age”. So there are frequent points through the first three sonatas especially Antheil will drop in a fox-trotty phrase or a bluesy harmony. Curiously, this “cutting edge” musical referencing dates the work more than anything else. What must have seemed edgy and on-point in the 20’s now simply sounds dustily quaint. By chance, another of my recent batch of discs to review included the Orchestral Sets of Charles Ives. Now if ever there was a composer not intent on making a societal splash it was Ives. He wrote music for his own interest – but interestingly those Sets, many of which pre-date the earliest Antheil by a decade, still challenge the listener and sound unrepentantly ‘modern’ in a way that Antheil does not.

But again I must stress that Yang and Rimmer are the best possible advocates for this music. Yang’s attack is fearless and laser accurate in a way that assures the listener that they are hearing the works exactly as Antheil intended. The recording itself made in a co-production with Deutschlandfunk Kultur Berlin is forensically close – Yang’s breathing often audible – not dry but closer as a listening experience than is wholly comfortable especially given the aggression of much of the music. According to DeWald, Antheil composed the first three sonatas while simultaneously working on his “experimental and intentionally shocking Ballet méchanique” which is the work featuring 16 pianolas, electric bells, propellers and sirens. Although nominally a futurist work again it has not aged well in the way that Edgard Varèse’s music written at much the same time still challenges and intrigues the listener. The Violin Sonata No.1 is written in four movements and is the longest of the four here running to 24:11. In turn the opening Allegro moderato is the longest section by some degree running to 10:18. DeWald references Béla Bartók as another recurring influence with the pounding clusters especially in the piano writing an obvious instance. Quite whether or not this is a “sonata” in any traditional sense of the word is far from clear. Of the four, only the fourth written around a quarter of a century later subscribes to obvious compositional processes that are recognisably ‘sonata-form’. Antheil also requires what might be termed ‘extended techniques’ of the violinist including increased bow pressure that causes the tone to break and distort as well as playing behind the bridge. I do not know if Antheil was the first composer to introduce such effects – certainly he was not the last – but as so often the case they seem to offer little musical ‘reason’ for being there except to grab the listener’s attention.

The Second and Third Sonatas followed on almost immediately after the first although both are significantly shorter and written in single movements; 8:49 and 14:16 respectively on this recording. According to DeWald No.2 continues Antheil’s experiments in “Musical Cubism”. The idea here is to combine “banal commonplaces” into a single collective musical image. This is achieved by an Ivesian collage of fragments of tunes – some known, some teasingly familiar combined into a montage. Antheil adds one more novelty to the pot by getting the pianist to finish the work playing an oddly dull rhythmic pattern on a pair of drums – one high and one low. Sonata No.3 does make a clearer nod at the use of sonata from by recapitulating the opening material at the end of the work. Again worth mentioning at this point just how brilliantly Yang and Rimmer engage with all of this music. Individually and together this must have taken an enormous amount of work to produce performances that are as authoritative as these. On my limited acquaintance with these works I must admit that they do not engage me greatly but if artists of this stature are as invested in them as they clearly are then there must be more to this music than I have yet discovered.

By 1947 Antheil’s Sonata No.4 immediately sounds more mainstream. He is by no means the only composer to go from being youthful revolutionary to later-life conservative. Not that this last sonata is conservative, but certainly in the context of modern music immediately post-war it is far from radical. Antheil returns to a multi-movement format – here three – and generally seems open to embracing older forms and styles with the middle movement even titled Passacaglia Variations. Antheil the musical magpie seems to have appropriated Shostakovich into his musical palette. The theme that opens the sonata – and recurs elsewhere too – to my ear sounds almost like a pastiche of the younger composer. Formally, this work seems the most balanced. The total works lasts 21:01 with each of the three movements of nearly equal length. One of the great values of this survey is to hear just how much Antheil’s style changed across the decades – after his death Virgil Thomson stingingly wrote “the bad boy of music… merely grew up to be a good boy.” Certainly the shock-inducing novelties of the 1920’s seem to give way to something more easily appealing but ultimately less individual.

Perhaps as a composer Antheil realised that he did not have the gifts to compete with the contemporary greats and that instead he needed a gimmick which his self-promotion and literal bells and whistles provided. But the problem with gimmicks is they lose their impact as soon as they have been revealed. This superbly played and authoritative disc reveals the truth that Antheil without gimmicks is actually a rather average composer.

Nick Barnard

Help us financially by purchasing from