Déjà Review: this review was first published in August 2001 and the recording is still available.

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

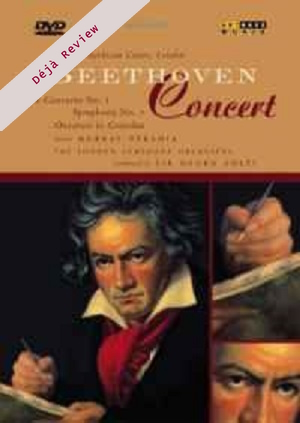

A Beethoven Concert

Coriolan Overture

Piano Concerto No 1

Symphony No 7

Murray Perahia (piano)

London Symphony Orchestra/Sir Georg Solti

rec. 1987, Barbican Centre, London

Arthaus Musik 100148 DVD [94]

As long as inexpensively priced products such as this superb release from Arthaus continue to enter the marketplace, the future of classical music on the twelve-centimetre silver disc must remain buoyant. But what kind of disc? The good old audio CD with its eighty minutes (maximum) of music must surely become increasingly under threat from the arrival of the DVD which offers fabulous stereo (and in some cases 5.1 digital surround sound), greatly extended playing times and fabulous picture quality.

Indeed, the history of Murray Perahia and the Beethoven Concertos sounds a cautionary yet instructive tale. Firstly, there was the CD cycle with Haitink, made so long ago that the label was still called CBS, not Sony. These were fine performances, considered at the time as good a set as could be obtained. Not long afterwards, a similar series with Neville Marriner at the helm arrived on Virgin VHS videotapes. Although they were not particularly well promoted, it was nevertheless noted by many enthusiasts that these tapes worked out at around two thirds of the price of the CBS CDs due to their extended playing times. Those early adopters who had invested in Nicam Stereo video recorders – linked up to their hi-fi systems – found themselves in the happy position of being able to enjoy PCM encoded stereo sound of almost CD quality from tapes of up to four hours in length. One or two of us actually listened to such videos without switching on the TV set at all and found that here was a new medium that offered fine sound without the need to get out of the armchair every hour or so. For a short while, VHS Stereo became the preferred method of recording whole concerts and operas from FM stereo radio.

But digital discs in one form or another were bound to win the day, as the DCC debacle soon proved. If tape was considered an inelegant medium, prone to damage, then DVD discs were bound to win public approval. Perahia’s performance of one of the Beethoven Concertos – the First – featured on this disc is the finest of the three he has made, with Solti giving superbly thoughtful support.

So if you want a compact disc of this programme of overture, concerto and symphony, this is the one to get. At over 90 minutes the disc remains compact, is called a DVD rather than CD and offers so much more. By all means listen to it as audio only; the BBC sound from this live March 1987 taping at the Barbican Centre, London (part of the Barbican’s fifth anniversary celebrations) is extremely fine with excellent balances throughout and no sense of the dryness that many concert-goers find in the hall.

But Digital Versatile Disc (as we now have to call it) began as Digital Video Disc and, fundamentally, this remains a video. Humphrey Burton’s direction is up to the very best BBC standards, avoiding both the extended shots of the conductor (à la Karajan) and the irritating switch to a particular instrument or section just before they play a major theme (very common). This is highly subtle direction, best exemplified in the first movement cadenza of the concerto where, fascinatingly, Burton dwells on the hands of Perahia, often employing differing camera angles to accentuate Beethoven’s dramatic leaps from bass to treble.

And what of Solti? Here he is as alive and virile as ever, with every nuance of expression clearly delineated by the wonderful picture quality. It’s hard to believe, when watching this DVD, that he is no longer with us. For those who enjoy debating the relative merits of conductors past and present, here is real evidence to support a point of view – not just an opinion based on audible results alone. The second subject of the concerto’s first movement contains one of those wonderful moments where the solo oboe enters soaring above a rhythmical string ostinato. Clearly, Beethoven knew his Mozart. One would expect the conductor to bring his oboist ‘in’. But not Solti. He trusted Tony Camden not to let him or the audience down, preferring instead, with his famous flick of the left wrist and with eyes firmly to the left, to ensure that the violins played rhythmically and at the correct dynamic. Such fascinating detail cannot be fathomed from sound alone.

Solti never rushed Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony. For many, the dance like figures require faster tempi throughout. But Solti also saw the work as part of the canon and there is a certain granite-like concentration in this performance which brings the symphony closer to the fifth and Eroica symphonies than usual.

Solti was ever the professional and his reaction to the warm applause at the end seems at first to bring a personal, almost selfish glow to the conductor without the orchestra’s apparent involvement. But this is an illusion; the admiration for certain conductors is the biggest factor in ensuring a full hall and Solti ensures his personal approval is thoroughly established with this audience.

That achieved, his generosity to his players in calling them to their feet with giant smiles on his face and with waves to individual orchestral members, clearly marked him out as a great man.

Simon Foster

Help us financially by purchasing from