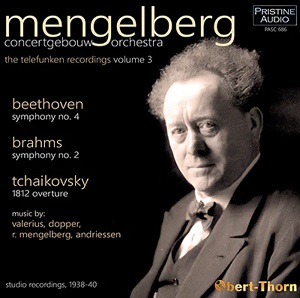

Willem Mengelberg (conductor)

The Concertgebouw Telefunken Recordings, Vol. 3

Jo Vincent (soprano)

rec. 1938-40, Grote Zaal, Concertgebouw, Amsterdam

Pristine Audio PASC686 [2 CDs: 125]

Not long after the issue of Volume 2 in this series of Mengelberg’s complete Telefunken Recordings, I’m delighted to find that Pristine has given us the third instalment. The first two volumes mainly contained large scale works and composers from the classical canon; here we certainly have works which fit those descriptions, but half of the set contains works by minor Dutch composers and a piece which, however popular it became, was regarded with contempt even by its composer.

As a Mengelberg “completist”, I’m very pleased to have the two 10-inch sides of the Dutch National Anthem and the Niederländisches Dankgebet, but, having played them once, in all honesty I can’t see myself ever playing them again. The Valerius has a certain hymn-like effectiveness, but the Anthem is as musically dismal as virtually all National Anthems tend to be.

We get going properly on track 3 with Beethoven’s Fourth Symphony. The performance is actually quite modern in approach in many aspects. The introduction has a nice sense of mystery, with almost none of the rubato one expects of Mengelberg. The allegro is exuberant, the articulation is quite “détaché”, and there is almost none of the portamento which would certainly have been found in a Mengelberg performance 10 or 15 years earlier. As with a number of the performances from these sessions, the woodwind are too distant. This may almost be a blessing as far as the vinegary Viennese-type oboe is concerned, but not for the other members of the family. The beginning of the second movement has a strong accent on the second note of the repeated bass accompanying phrase which contrasts very effectively with the lovely legato of the main theme (again, hardly any portamento or rubato – Mengelberg was clearly moving with the times), but with increasingly expressive moulding of the line as the movement progresses (listen about 3 minutes in) with some gorgeous woodwind phrasing. The third movement is very “unbuttoned”, and the only really old-fashioned aspect of the performance is in the marked slowing down for the trio. The fourth movement is weightier than would be expected today, with heavy accents, but I find it works perfectly convincingly.

The remainder of the first CD is taken up with Brahms’ Second Symphony. In the first movement, the tempo is quite swift, and again the portamento and rubato that we might have expected are largely absent. There is more of it than in the Beethoven, but only at about 3.30 into the movement do we feel a real pushing-forward of the tempo – though there is, surprisingly, no rubato between 6 and 6.40. This reading is certainly not the amiable, rural piece that some see; there is a real sense of drama and disquiet here, which seems to me absolutely Brahmsian. At the beginning of the second movement Mengelberg makes quite a lot more use of portamento than we have seen thus far on the CD, and passionately so at 3.00. The whole movement is strong and has great momentum with nothing “amiable” about it. As he did in the second movement of the Beethoven, in the third movement Mengelberg mixes strong (later on quite fierce), detached articulation in the woodwind with wonderful legato string phrasing to great effect. The finale also has tremendous momentum throughout; there is no relaxation here, the music thrusts passionately till the very end. I found this a most convincing performance.

The second CD begins with the three Dutch works I mentioned. Dopper’s Giaconna gotica is, I would maintain, no masterpiece, but it is enjoyable, if rather “bitty”. It reminds me of Stokowski’s orchestration of Bach’s Passacaglia and Fugue in C minor, only even more technicolour in its use of percussion. It also shows off the virtuosity and depth of colour of the Concertgebouw Orchestra to great effect. The recording does not in any way let it down – it is almost impossible to believe that it was recorded over 80 years ago.

The Salve Regina by Mengelberg’s nephew Rudolf is another piece more notable for its atmosphere than its musical content. It is quite enjoyable and well-orchestrated, but I think you would need a lot of hearings before you would be able to recall a single detail of it from memory. The Andriessen is a better piece, but again it does not lodge easily in the memory. In these two pieces, Mengelberg is joined by one of his favourite singers, the Dutch soprano Jo Vincent, who sang with him regularly in all sorts of repertoire, and can be heard in the live recordings of Mahler’s Fourth, Brahms Requiem, Bach’s Matthew Passion and several other shorter pieces. I’m very fond of her commercial records; she can be a lovely singer, with a beautifully pure sound and considerable intelligence and sensitivity to text, but I don’t think she is at her best in these recordings. She is rather swoopy, and both her attack and her pitching are not always as precise as they should be (and usually were). I was also surprised at her comparatively flabby diction; the words often don’t really come over. I am always really irritated if I don’t have the text for any vocal recording, so after this review I have attached the Latin texts and my translations for both the Salve Regina and Magna res est amor for those who would find them useful.

The final piece was one of my dad’s favourite pieces of music, but one which I don’t think I’ve listened to since he died 35 years ago – Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture. When even its composer wrote that it was “… very loud and noisy, but [without] artistic merit, because I wrote it without warmth and without love” it helps one not to feel guilty about not liking it. I would guess, though, that Tchaikovsky was rather less sniffy about the considerable wealth that it brought him. In his note, Mark Obert-Thorn describes Mengelberg’s recording as “one of the most exciting – and musical – performances of the work ever made.” I’m not so sure; I found it surprisingly tame and unexciting, and can’t help thinking that “musical” here simply means that it is very well-mannered and restrained. But when you have a piece whose only real point is hell-for-leather excitement, is that really a “musical” approach? I can’t help wondering if Mengelberg, for all his love of Tchaikovsky’s music and mastery of its performance, didn’t also think it was pretty shabby piece. 1940 was slap bang in the middle of the period of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact (1939-1941), and it is possible that Telefunken persuaded Mengelberg to record it as part of the propaganda for this example of Nazi duplicity. I don’t imagine it lasted long in the catalogue after Hitler launched Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of Russia, in July 1941.

As always with Mark Obert-Thorn’s transfers, the sound quality is excellent. These recordings were state of the art at the time, so he has comparatively problem-free source material, but he has also sourced excellent copies, so surface noise is minimal and high frequencies come over very well indeed. This is another first-rate addition to Pristine’s Mengelberg series.

Paul Steinson

Availability: Pristine ClassicalContents

CD 1

Traditional – Wilhelmus van Nassouwe (orch. Mengelberg) rec. 1 December 1938

Valerius – Niederländisches Dankgebet (orch. Wagenaar) rec. 1 December 1938

Beethoven – Symphony No. 4 in B flat major, Op. 60 rec. 1-2 December 1938

Brahms – Symphony No. 2 in D major, Op. 73 rec. 9-11 April 1940

CD 2

Dopper – Ciaconna gotica rec. 12 April 1940

R. Mengelberg – Salve Regina rec. 12 April 1940

Andriessen – Magna res est amor rec. 12 April 1940 4

Tchaikovsky – Ouverture solennelle ‘1812’ rec. 11 April 1940

The texts below include my translations of the Latin. I have intentionally gone for an approach which helps the reader to follow the individual word order easily rather than giving a stylish or poetic translation, as anyone who knows the beautiful Catholic liturgical version of the Salve Regina will immediately recognise.

Salve Regina

Salve, Regina, mater misericordiae: Hail, Queen, mother of mercy:

Vita, dulcedo, et spes nostra, salve. our life, sweetness, and hope, hail.

Ad te clamamus, exsules, filii Hevae. To thee do we cry, exiles, children of Eve.

Ad te suspiramus, gementes et flentes To thee we sigh, mourning and weeping

in hac lacrimarum valle. in this valley of tears.

Eia ergo, Advocata nostra, You therefore, our advocate,

illos tuos misericordes oculos those two merciful eyes

ad nos converte. Turn toward us.

Et Iesum, benedictum fructum ventris tui, And Jesus, the blessed fruit of thy womb,

nobis, post hoc exsilium ostende. After this exile, show us.

O clemens, O pia, O dulcis O clement, O loving, O sweet

Virgo Maria. Virgin Mary.

Magna res est amor (De Imitatione Christi, Bk. 3 Ch. 5 – Thomas à Kempis [1379/80 – 1471])

Magna res est amor, magnum omnino bonum, A great thing is love, a great good in all respects,

Quod solum leve facit omne onerosum, Which alone makes light all that burdens us,

Et fert aequaliter omne in aequale. And knows how to bear all things with equanimity.

Nihil dulcius est amore, nihil fortius, Nothing is sweeter than love, nothing stronger,

Nihil altius, nihil latius, nihil jocundius, Nothing higher, nothing broader, nothing pleasanter,

Nihil plenius nec melius in cœlo et in terra. Nothing fuller or better, in heaven and on earth.

Quia amor ex Deo natus est, nec potest, Because love is born of God, it cannot,

Nisi in Deo, super omnia creata quiescere. Except in God, find rest beyond all created things.

Magna res est amor, magnum omnio bonum, A great thing is love, a great good in all respects,

Quod solum leve facit omne onerosum, Which alone makes light all things that burden us,

Et fert aequaliter omne in aequale. And knows how to bear all things with equanimity.