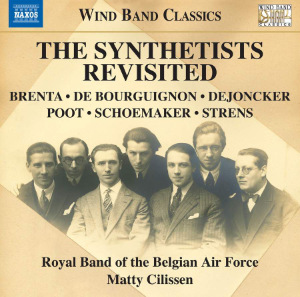

The Synthetists Revisited

Jules Strens (1893-1971)

Gil Blas Op.2 (1921)

Marcel Poot (1901-1988)

Tartarin de Tarascon (1924)

Francis de Bourguignon (1890-1961)

Récitatif et Ronde Op.94 (1951)

Gaston Brenta (1902-1969)

Zo’har (1928)

Théo Dejoncker (1894-1964)

Guitenstreken [no date]

Maurice Schoemaker (1890-1964)

Brueghel Suite (1928)

Royal Band of the Belgian Air Force/Matty Cilissen

rec. 2022, Perwex, Belgium

Naxos 8.579135 [73]

In September 1925, seven Belgian composers, all pupils of Paul Gilson at the Brussels Conservatoire, formed a composers’ collective. They chose the name Les Synthétistes, because they wished to distance themselves from the still prevailing Romantic style in some Belgian music circles. They were also known as the Brussels Seven – a tip of the hat to the Russian Five or, closer in time, to the French Groupe des Six. There were no symphony orchestras in Belgium then, so they either transcribed their orchestral works for wind band or wrote new pieces for winds. They forged strong links with Arthur Prevost and the Band of the Belgium Guides, who for quite a long time were highly regarded as champions of Belgian music. The Band’s next music directors maintained that close relationship. The other bands of the Belgian armed forces have continued this championing to this day. This is fortunate, because there is still much fine music to bring to light again.

The Synthetists’ works on this programme have been hitherto rarely heard, let alone recorded: most are new to the catalogue. The oeuvre of these composers – except maybe Marcel Poot – is uncharted territory for many a music lover. The first of them, Jules Strens, may be best known for the short and delightful Danse funambulesque (1929). He has a wide-ranging list of composition: many instrumental pieces, including four string quartets, and vocal works. One of his last pieces is the splendid orchestral Ensorciana of 1970 based on James Ensor’s paintings. Here we get a more substantial work, Gil Blas, variations for orchestra transcribed for wind band in 1955. They are obliquely based on the picaresque novel Gil Blas de Santillane by Alain-René Lesage (1668-1747). The hero’s adventures in Spain explain the Spanish turns of phrase in Strens’s music. The variations more or less follow the course of Gil’s adventures, pleasant and unpleasant (he found himself imprisoned), but one need not know the story to enjoy this lively and colourful score.

Marcel Poot he has a very long list of works, and he wrote for every medium imaginable; his music for brass or wind band enjoys much exposure among the interested. His music is often characterised by earthy and robust humour, always with the odd pinch of spice or irony, but is still capable of sincere, unsentimental tenderness. He always seemed to me the musical Brueghel of our time. His suite Tartarin de Tarascon is no exception: The tale of the would-be adventurer by Alphonse Daudet (1840-1897) is not without humour, irony and eventually empathy with poor Tartarin.

Francis de Bourguignon trained as a pianist in the class of Arthur De Greef, and took harmony lessons with Paul Gilson. He concentrated on his pianistic career. Injured at the outbreak of World War I, he was evacuated to England before deciding to leave for Australia. For several years, he was Nellie Melba’s permanent accompanist, travelling around the world. While doing so, he got in touch with some of the newest musical trends. Back in Belgium, after further lessons with Paul Gilson, he picked up his composing activities. Some of his pieces, somewhat popular, are still heard too rarely. Récitatif et Ronde is a fine short piece, also known in a version for trumpet and orchestra. The music sometimes harks back to Stravinsky (think Petrushka). There is a good opportunity for the trumpet, superbly played here by Michaël Tambour, to shine in a sometimes tricky concertante role.

Gaston Brenta’s name was reasonably familiar on the Belgian musical scene. He wrote Piano Concerto No.2 as the test piece for the 1968 Queen Elisabeth Competition, and in 1946 composed a fairly imposing symphony. His music might be described as urbanely neo-classical but this does not apply to the piece recorded here: Zo’har, a choreographic essay after the eponymous novel by Catulle Mendès (1841-1909). In truth, I have no idea what Mendès’s work as a whole may be. (He was one of the founders of Le Parnasse, and he wrote a quantity of poems, plays and novels, which are little known today. Interestingly, he was one of the partners of Augusta Holmès with whom he had several children. And his end is shrouded in mystery: his body was found along a Paris railway track.) All that matters here is that Brenta’s piece – concerning an episode in the novel – is among the most remarkable things that he ever penned. I for one was not prepared to hear music of such rawness and brutality, in strong contrast to Brenta’s own urbane appearance. Zo’har is undoubtedly a great achievement, and I would like to hear it in its original orchestral guise.

In total contrast, Théo Dejoncker’s short piece Guitenstreken (gaminerie – playfulness – in French) brings relief after the hothouse atmosphere of Zo’har. It is the kind of music that accompanied silent films. Dejoncker was mainly known as theatre conductor in Brussels, and was second conductor of Orchestre symphonique de l’I.N.R. (Belgian Radio Symphony Orchestra) alongside Franz André. His fairly sizeable output cover almost every genre, but it is barely known today.

Maurice Schoemaker may be best remembered for the brilliant Feux d’artifice (fireworks) of 1922, a sparkling display of orchestral mastery. He too had a substantial output in almost every genre, also little known. Orchestral music has pride of place in his output but he wrote chamber and vocal pieces, incidental music for stage and radio, and three operas. His fairly substantial Brueghel Suite started life as a ballet for Le Roi boit, sketched as early as 1920. It received its première at La Monnaie in 1929, and was repeated in 1930 during the World Exhibition in Antwerp. It was then given the title Evocations flamandes. Later it was reworked as an orchestral suite, heard here. This is a superb score of colourful and evocative music that repays repeated hearing (as does the rest of this collection). I would like to hear it in its orchestral guise, too.

The back cover says: “Works by the collective’s ‘master’ Paul Gilson and the seventh member, René Bernier, can be heard on the digital single 9.70351.” This appendix to the present disc can be bought here.

The disc is for anyone who wants to hear worthwhile though generally much neglected music by some distinguished Belgian composers. It clearly deserves to be heard, especially when played with commitment and enjoyment. I hope that this well filled, well played and well recorded release will be followed by some more.

Hubert Culot

Help us financially by purchasing from