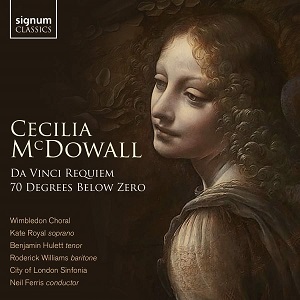

Cecilia McDowall (b. 1951)

Da Vinci Requiem (2019)

70 Degrees Below Zero (2012)

Kate Royal (soprano); Benjamin Hulett (tenor); Roderick Williams (baritone)

Wimbledon Choral

City of London Sinfonia/Neil Ferris

rec. 2022, St Augustine’s Church, Kilburn, London

Texts & English translations included

Signum Classics SIGCD749 [57]

The booklet to this fine disc carries an introduction to the Wimbledon Choral that seems to have been written by one of the members. The writer’s enthusiasm is well founded: this is as fine an amateur choir as you are likely to find. To celebrate the hundred or so years of its existence, the choir decided to commission a major work from a prominent composer of choral music. Cecilia McDowall duly produced her Da Vinci Requiem, in which she sets passages taken from the familiar Requiem text alongside extracts from the writings of Leonardo.

The work opens with a mellifluous ‘Introit and Kyrie’ whose atmosphere is anxious and apprehensive, an appropriate response to Leonardo’s ominous words imploring us to devote ourselves to work ‘Because movement will cease before we are weary of being useful’. The soloists’ musings over constantly moving choral lines do little to alleviate the rather oppressive atmosphere. The second movement is a setting of words written by Dante Gabriel Rossetti as a response to Leonardo’s painting The Virgin of the Rocks. Rossetti’s view of the painting is a gloomy one, to which McDowall’s tolling accompaniment under the florid soprano line is a fine response.

The third movement, ‘Lacrimosa’, is described by the composer as ‘unashamedly melodic’. I don’t know why she felt the need to qualify the word: the music certainly is melodic, with rich harmonies as accompaniment. Prominence is given to oboe and harp, and the choir sings it beautifully, a welcome contrast after Rossetti’s rather sombre reflections.

The fourth movement, ‘Sanctus and Benedictus’, forms the central section of the arch structure described by the composer in her booklet essay. There is nothing from Leonardo here, only the familiar Latin text. It is full of energy and rhythmic drive, extremely jolly, and is surely a joy to sing. The glockenspiel is in evidence, but the Sanctus bells are even more ingeniously evoked by cascading peals in the choral parts. The Benedictus is, as is customary, more restrained, but the vitality of the opening returns with the closing hosannas. The musical material of the fifth movement, ‘Agnus Dei’ is, like Duruflé’s wonderful Requiem, derived from plainsong. The choir is silent in the sixth, leaving the stage clear for the baritone soloist in words where Leonardo explores the similarity between sleep and death. How many listeners will share the view that ‘Since a well-spent day make you happy to sleep, so a well-used life makes you happy to die’ is an open question.

The idea of perpetual light and eternal rest, as found in the following ‘Lux aeterna’, is not, I think, a concept that appeals to everybody. Yet there can be no doubt that the text, annulling as it does the darkness and finality of death, is meant to encourage us. McDowall’s response to this is very fine indeed, the word ‘radiant’ being, for once, a sufficient word to describe the music, and to which we might add ‘surging’ and ‘richness’. The movement is properly conclusive, but McDowall is too original a composer to produce a conventional ending. No, in the closing bars the music is indeed directed to the upper reaches, ‘an allusion’, writes the composer, to ‘Leonardo’s concept of The Perspective of Disappearance’; but the voices eventually fall silent and the texture thins, leaving the final notes to solo violins, a striking and touching close to an important and deeply impressive work.

Da Vinci Requiem was first performed in May 2019, with the Philharmonia, but otherwise the same performers as on this subsequent recording. Giving that premiere was, we read, ‘very exciting indeed’, and the Wimbledon Choral – whose every member is named in the booklet: an excellent idea – will be justifiably proud of the importance of that event. Neil Ferris conducts a totally convincing performance, and, as the choir’s Music Director, will be in large part responsible for the quality of the choral singing. I find the choral writing is at once more attractive and convincing than that for the soloists, both of whom acquit themselves very well.

The City of London Sinfonia and Neil Ferris provide a sensitive accompaniment to tenor Benjamin Hulett in the coupling, 70 Degrees below Zero. The work was commissioned by the Scott Polar Research Institute, with additional funds from the RVW Trust and the Richard Hickox Fund for New Music. It is scored for tenor and orchestra, and runs for about sixteen minutes. Scott’s own writings – taken from documents found in his tent – are set alongside two poems by Seán Street written at the composer’s request especially for this work. The work opens with an extract from Scott’s Journal early in the final phase of the journey to the Pole, spoken by the soloist as the music steals in underneath. Its optimistic tone is in bleak contrast to the later, deadpan, announcement that the Pole has been reached, only to find the flag already placed there by the rival expedition led by Roald Amundsen. The orchestral writing in the second movement, ‘The Ice Tree’, powerfully evokes the cold and featureless landscape. It is here that we first encounter a wide, rising leap in the tenor line that is to become even more significant later. The final movement is a setting of Scott’s letter to his wife, written when he must surely have known he and his companions were doomed, and which contains the phrase that gives the work its title. McDowall describes the opening music as ‘gentle’, with which one can only agree, but also as ‘folksy, which seems strange. The gentleness does not last: McDowall fascinatingly brings passion and agitation to the music when a more conventional reading of the words might have suggested acceptance and stoicism.

I first encountered Benjamin Hulett in 2009 in a recorded collection that included Vaughan Williams’s Songs of Travel. I am no less impressed by his remarkable singing now than I was then. The tenor line is often ungrateful to sing, but he manages everything beautifully, knowing instinctively, so it seems, where to place emphasis and where to change pace. The orchestral writing is superb, more memorable to my mind than the vocal writing. Indeed, the composer rather shows her hand when she writes of the moment that ‘the orchestra becomes the writer of [Scott’s] letter’. This is, none the less, another highly impressive work, one that, in particular, ends wonderfully, with the return of the tenor’s widely rising phrase to the words ‘God bless you my own darling’.

William Hedley

Previous review: John Quinn (April 2023)

Help us financially by purchasing from