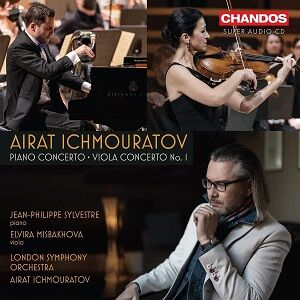

Airat Ichmouratov (b. 1973)Piano Concerto, Op. 40 (2012-13, revised 2021)

Viola Concerto No. 1, Op. 7 (2004, revised 2021)

Jean-Philippe Sylvestre (piano); Elvira Misbakhova (viola)

London Symphony Orchestra/Airat Ichmouratov

rec. 2022, LSO St Lukes, London

Chandos CHSA5281 SACD [76]

I must confess that this composer is new to me, but this is the third recording of Ichmouratov’s music to be released by Chandos. Other companies such as Warner Classics, Analekta, ATMA Classique, and CBC have issued much of his orchestral and klezmer music.

Airat Ichmouratov was born in Kazan in 1973 from a family of Volga Tatars, and studied clarinet at the Kazan Conservatoire prior to emigrating to Canada in 1998, where he continued his studies in clarinet, composition and conducting at the Université de Montreal. In Canada, he founded the Muczynski Trio, which won the First Prize and Grand Award at the Canada National Music Festival in 2002, and the Contemporary Chamber Music Competition in Krakow in 2004. He has established a successful conducting career, starting with the Orchestre symphonique de Québec, the Orchestre symphonique de Longueuil and Les Violons du Roy and he is the leader, clarinettist and arranger of the klezmer group Kleztory. He has worked with I Musici de Montréal, the Brussels Chamber Orchestra, Taipei Symphony Orchestra, the Tatarstan National Symphony Orchestra, and also the Tatarstan State Opera and Ballet Company in Puccini’s Turandot and Verdi’s Rigoletto on their European tour in 2012.

Ichmouratov’s music is entirely tonal, with a neo-Romantic emphasis and noted by some reviewers as somewhat lacking in originality, yet it has been received favourably in recent recordings; Yannick Nezet-Seguin states. ‘Airat is a communicator in the best sense of the word. His music immediately grabs the listener, and a journey starts: storytelling, landscapes, emotions… It is precious to have such music in our world today.’ Ichmouratov’s latest composition is an opera based on Victor Hugo’s novel L’ Homme qui rit (The Man who laughs). Musicians who have performed his music include Maxim Vengerov, Yuli Turovsky, Alexander Gilman, Stéphane Tétreault and Yegor Dyachkov.

The piano concerto opens Andante affettuoso, with an attractive theme, and the piano enters with a romanticism which evokes memories of Rimsky Korsakov and composers of the Russian nationalist school. The piano adopts a brisk idea which ranges in mood from sentimentality to melancholy passion. I am reminded of Soviet film composers such as Doga and Tariverdiev, whom the composer must have heard in his youth in the former Soviet Union, and are all accessible on YouTube. Often the music sounds schmaltzy, like old Hollywood movies, yet beautifully orchestrated by Ichmouratov and stunningly played by Canadian pianist Jean-Philippe Sylvestre. What is perplexing is the appearance and disappearance of ideas without development. There is a long cadenza by the soloist that is reminiscent of a popular Russian folk song.

The second movement, Grave solenne, begins with a slow, almost mourning theme on the strings which leads to a climax, and we hear a solo harp playing a child-like theme that is picked up by the woodwind, then a meditative idea dominates a cadenza on the piano backed by the orchestra. The upbeat finale, Allegro moderato, reminds me of Soviet piano concertos by Kabalevsky and Khrennikov with dashes of wit in its playful, attractive themes. I was also reminded of Nino Rota’s music from Fellini movies. The orchestra under the composer’s direction certainly does its best to bring out all the magical colours of the score, and the playing of the Sylvestre, to whom the concerto is dedicated, is outstanding.

The Concerto No. 1 for viola is dedicated to the soloist Elvira Misbakhova , who is clearly a very talented violist. This is a more interesting piece; the opening Andante begins forebodingly on the low strings and surges to the entry by the viola in a bewitchingly beautiful theme, yet soon the playing descends into a schmaltzy Hollywood sequence of trivial orchestral music. The viola cadenza of the slow movement, Recitativo, is captivating. The finale, Allegro – Presto, is upbeat, with a lovely, carefree viola theme stunningly played by Misbakhova, and a mix of klezmer and Russian folk ideas bringing the concerto to a close.

Ichmouratov is a talented orchestrator, yet his music is devoid of originality – I suspect his creativity will provide cinema and television with plenty of material. Frankly, I am not surprised the piano concerto languished for two decades in the composer’s desk. Of the two pieces, the viola concerto is more gifted with touches of novelty for the viola. One hopes it will become in demand for violists, but Ichmouratov lacks the imagination to offer music of wider interest.

The Chandos recording is typically state-of-the-art, and the London Symphony Orchestra, well directed by the composer, plays magnificently. This disc will interest those who enjoy lively cinematic music, and I would suggest that the cinema could offer Ichmouratov a successful and secure future.

The 32-page booklet includes texts in English, French and German on the music, composer and performers with black and white and colour photos. This recording will be popular with those who like to listen to easy music – ideal perhaps for a long car journey – but I cannot recommend it to serious collectors of contemporary music.

Gregor Tassie

Help us financially by purchasing from