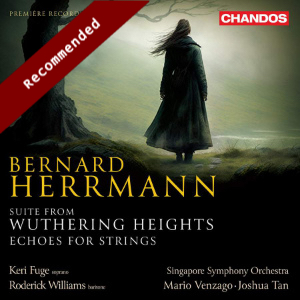

Bernard Herrmann (1911-1975)

Suite from Wuthering Heights (1943-1951 as adapted by Hans Sørensen in 2011)

Echoes for String Quartet (arr. Hans Sørensen for string orchestra) (1965, arr. 2011)

Keri Fuge (soprano – Cathy), Roderick Williams (baritone – Heathcliff), Singapore Symphony Orchestra/Mario Venzago, Joshua Tan

rec. 2020-22, Esplanade Concert Hall, Singapore

Chandos CHSA5337 SACD [80]

Bernard Herrmann was an unmitigated Anglophile. This love affair with English literature and language permeated so much of what he did and wrote. It was early on the scene too. Notably, his works in the 1930s for CBS Radio included melodramas – spoken word over orchestra. These included various tone poems in which – as in various Fibich pieces – an actor’s voice ramps up the intoxication of the words. These works ran from Weep You No More, Sad Fountains; Annabel Lee; The Willow Leaf; Cynara (cf Delius’s Dowson setting); The Happy Prince; The City of Brass; A Shropshire Lad and La Belle Dame Sans Merci; the latter was also set by Cyril Scott, whose two piano concertos Herrmann recorded for Lyrita with John Ogdon. It’s well past time that the melodramas were systematically recorded. In later years the liquor of a certain English mood and landscape soused scores such as Herrmann’s grand opera Wuthering Heights, the film score for Jane Eyre – more Brontëand written in the same year as the opera – For the Fallen and The Fantasticks.

Dedicated to his wife, the opera Wuthering Heights is a “Lyric Drama in Four Acts and a Prologue” with a libretto by Lucille Fletcher “after the novel of Emily Brontë”. No doubt boosted by his film score revenue, Herrmann brought about (and conducted) a recording of the opera even if it still awaits a fully staged production. In May 1966, against the odds it was recorded, in all its glory by Pye Records on 4 LPs (CCL 30173). Herrmann conducted the Pro Arte Orchestra. The cast numbered Morag Beaton as Cathy (soprano), Donald Bell as Heathcliff (baritone), Joseph Ward (as Edgar Linton), Elizabeth Bainbridge (as Isabel Linton), John Kitchiner, Pamela Bowden, David Kelly and Michael Rippon. Pye faded away into the sunset but the tapes were rescued and issued in another boxed set by Unicorn Kanchana in 1972 (Unicorn UNB 400). A CD transfer appeared on Unicorn-Kanchana UKCD 2050. I won’t outline all that Unicorn did for Herrmann. Suffice to say that in the 1970s the label did swathes of his music and followed that up with CDs in the new era of the 1980s.

With masterly aplomb and technical sensitivity, Chandos have done a great deal for Herrmann’s music. Before this disc they have recorded a film music collection with Rumon Gamba and the BBCPO (Citizen Kane) and one disc centred upon the Herman Melville epic Moby Dick. Now, after having levelled up their projects in Denmark and Manchester they have directed their peripatetic roving eye and team to the present disc through a Singapore connection. One thing is for sure; this disc like the others has been as surefooted as a mountain goat. Their choice of orchestra, conductors and technical team is nothing short of perfect. Mario Venzago who has a niche reputation for Bruckner and especially Othmar Schoeck – how Herrmann would have exulted in Schoeck, if not Bruckner – proves an ideal choice for what amounts to this Wuthering Heights cantata. Both he and Joshua Tan (Echoes) have the measure of Herrmann and put not a foot wrong.

Hans Sørensen is the imperious but discreet voice in the present Chandos project. From an opera that has barely been heard despite a handful of productions and recordings he has crafted what has been termed a “Suite” running to a telling one hour. Steeped in the world of film music and film studies, Sørensen has also been a force for good in Danish broadcasting and at the head of the Göteborg and now Singapore orchestras. His work on Wuthering Heights In fact it comes across as more of a cantata, akin to but longer than the Prokofiev Alexander Nevsky or Ivan the Terrible cantatas. Perhaps in years to come Sørensen’s work on the cantata will be criticised but, for now in our real world, Sørensen has given new life to an extensive work drawn from a little-known opera by a composer popular in the film music world. Live productions of the full work have been fewer than Howard Hanson’s Merry Mount; in April 2011, Minnesota Opera entered the lists under Michael Christie. There was another live performance, this time with the Orchestre National de Montpellier conducted by Alain Altinoglu, with Boaz Daniel and Laura Aikin (July 2010). This came out on three CDs under the resonant French title “Les Hauts de Hurlevent” on Accord/Universal.

The cantata, as it emerges is a thing of Delian/Puccinian ecstasy. Passions are at full stretch although time is set aside for the heart-balmy effect of birdsong. The work explodes onto the scene in medias res with a cannonade of crashing Gothic drums. As the singing rears its head we are reminded of reaching upwards of Delius’s Seadrift; the singer is Roderick Williams (recently heard singing at the Coronation service). His voice is agreeably recessed – not far back but enough to tell you that the solo voices will bed down as much part of the orchestra as they are major protagonists (tr. 1). Keri Fuge is the soprano and she is most capable, steady and sweet of tone; a very touching presence throughout. The two singers, when in duet, recall Delius’s A Village Romeo and Juliet, Hadley’s The Hills, Howells’ Hymnus and Missa Sabrinensis and indeed moments in Hermann’s own The Fantasticks. Vigour and aspiring passion are engaged, although poetry intervenes too and this breasts aside the melodrama (tr. 4). Delius again thrusts forward in what comes across as a parallel with Once I dwelt in a populous city. Ecstasy seems to be the goal and, sun-dappled and melting, it is achieved. There are continuous instrumental coups such as the rocking harp and string figuration in tr. 6. The Nocturne (for orchestra alone) at tr. 7 is matched by the lulling lullaby ostinato strings that curvet back and forth. It’s a magical effect. Soon we return to doomed passions (Tr. 10) and resentment hits out, hard as anthracite and soft as lignite on the words “how cruel and false you have been, Cathy” before the full and splendidly despairing unfolding of a melody that keeps delivering.

Track 14 has brooding woodwind and it comes as no surprise that the composer’s marking at this point is tenebroso. That mood is sloughed in Tr 15 where violence rears up like Sondheim’s Sweeney Todd as he addresses his razors as an extension of his avenging agency. The next episode has a triumphal barking brass edge and a stygian choir that flows in the veins of the brass. Cinder-ash glows within the darkness and the score rises again to a love duet of doomed ecstasy redolent of Tristan und Isolde and Boughton’s The Queen of Cornwall. Heathcliff calls out “Cathy! Cathy!” in despair. Finally we come to an Adagio tenebroso picking up, in rounded mood form, from the start of the work – a retreat into darkness.

This is indeed a great and extremely effective recording, drenched in splendour from treble to bass. Music and performance that is subtle but stern with nothing of the dayglow treatment.

Echoes in a single 20-minute track lacks the dynamic coil and recoil of the same composer’s Sinfonietta but is a well worthwhile work for string orchestra – again at the hand of Hans Sørensen. In this he has done valuable work of the type that has previously been done for the quartets of Shostakovich, Vainberg and Walton. The work’s episodes are: Moderato e mesto – Valse lente – Moderato – Lento – Moderato Allegro and Moderato. Herrmann has no qualms about light touch delays between and within these episodes. They do not have any dysjunct effect on the listener, such is Tan’s feeling for the work. It radiates a glum concentration and often and uncannily brings to mind and vision a lichen-shrouded cemetery. Gothic is all. Bowed stone angels bend down over the massive vaults. This is a subdued mood that ‘spoke’ to Herrmann. In its span other works are lightly touched upon including at 10:05 Elgar’s Sospiri, Sibelius’s Rakastava and his own music for Psycho (6.44). Although this is a work that Sibelius might have given the title Malinconia (a marking also adopted by Herrmann in Wuthering Heights) a smile – if regretful – is broken for example at 4.29 where unfolds one of those irresistible Herrmann ideas: bittersweet and a precarious littoral between delight and despair. There are other moments of variety too, for example the night-ride section at 6.44, which is inhabited by buzzingly quiet yet peckingly intense play. At 13.22 there is a powered race with urgency whipping things forward. At 14.40 there is a suite of heart-bursting expostulations, played fff, for the whole string orchestra. As the piece closes its pages shudders and shivers emerge at 19:53. Intelligent and telling use is made of Sibelian ostinato tempered with the sort of writing to be heard in Tippett’s Fantasia Concertante on a Theme of Corelli. This is a very serious work which is empowered by a glumly impressive writing threaded through the gloom and glum of the human condition.

There are excellent notes by David Benedict, although for my liking the opaque descriptions of the music failed to hook my attention, which drifted accordingly.

The Amici Quartet made the first recording of Echoes in the 1960s; this was issued in 1972 coupled with the Clarinet Quintet Souvenirs de Voyage [29:01] on a Unicorn LP RHS332. Souvenirs was played by the Ariel Quartet with clarinettist Robert Hill. This was out on the market for a brief spell on Unicorn CD UKCD2069. There have been other recordings of these works but none uprated as Echoes is for full string orchestra.

Chandos have given us a Herrmann disc that ranks up there with the Herrmann greats including the Charles Gerhardt/NPO film music collection from 1973. This great and extremely effective recording is drenched in splendour. Both music and performance are subtle, stern and of the utmost eloquence. If that praise is high then it is more than merited.

Rob Barnett

Help us financially by purchasing from

Suite from Wuthering Heights

1. I Prologue. The Snow and Wind. Allegro tumultuoso – Lento.Molto sostenuto e tempestoso – (Heathcliff: ”Oh, Cathy! Come in. Oh, come in”)

2. II Act I, Scene 1. Allegretto pastorale (molto tranquillo) (Cathy: ”I have been wandering through the green woods”) – with Heathcliff

3. III Act I, Scene 1. Sunset. Moderato (Cathy: ”Do you remember the day you first came to Wuthering Heights!”) – with Heathcliff

4. Act I, Scene 1. Andante con moto (molto moderato) (Heathcliff: ”On the moors, on the moors”)

5. IV Act I, Scene 1. Lento tranquillo (Cathy: ”Look, the moon”) with Heathcliff

6. V Interlude (Nocturne). Lento assai

7. VI Act I, Scene 2. Adagio, molto espressivo e triste (Heathcliff: ”I am the only being, whose doom no tongue would ask”)

8. VII Act II. Adagio tranquillo (Cathy: ”I have dreamt in my life dreams that have stayed with me for ever”)

9. VIII Act IV. Meditation. Andante con malinconia

10. Molto lento (Cathy: ”Heathcliff. Heathcliff”) – with Heathcliff

11. Act IV. Allegro molto moderato (agitato e appassionato) (Cathy: ‘Will you say so, Heathcliff!’) – with Heathcliff

12. Act IV. Molto moderato ma liberamente (Cathy: ”Open the window. Let me breathe the wind”)

13. IX Act IV. Death of Cathy. Molto moderato e molto tranquillo (Cathy: ‘

shall not leave you, you are my soul”)

14. Act IV. Largo assai (tenebroso)

15. X Act IV. Allegro feroce (Heathcliff: ”May she wake in torment!”)

16. XI Act IV. Lento, molto sostenuto e tempestoso

17. XIII Act IV. Adagio (tenebroso) (Soprano Voice: ”Heathcliff!

Heathcliff! Let me in”) –

18. XIII Act IV. Lento, molto sostenuto e tempestoso

Molto appassionato (Heathcliff: ”Oh, Cathy! Come in, oh come in!”) –

with soprano voice

19. XIV Act IV. Adagio tenebroso