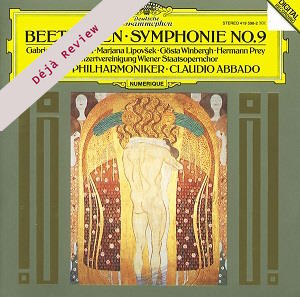

Déjà Review: this review was first published in July 2006 and the recording is still available.

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Symphony No. 9 in D minor, op.125 (1824)

Gabriela Beňačková (soprano), Marjana Lipovšek (contralto), Gösta Winbergh (tenor), Hermann Prey (baritone)

Vienna State Opera Chorus

Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra/Claudio Abbado

rec. live, May 1986, Musikverein, Grosser Saal, Vienna

Deutsche Grammophon 4775005 [73]

Your first impression may be of a certain inertness, but I think you will quickly be impressed at how steadily the first movement moves ahead, with the inexorable tread of a cortège, even the tragic weight of a Via Crucis. With such a burden of pain, and at a broad tempo, the music might easily have sagged, but there is also a Toscanini-like grip to lead it forward. The sound, furthermore, is never heavy. Abbado probes into the textures with a Boulez-like searchlight. Many details which I had noted with my eye but never really heard are not only present but made to take their place in the overall scheme. Immensely impressive.

The scherzo, at a moderate speed and with all repeats, manages to maintain an air of mystery while the trio is extremely perky. The slow movement is again broad but never becalmed. The phrasing and playing are extremely beautiful. The great melodic arches do not reach out to the millions as they are sometimes made to do. Rather, this is a very interior meditation, a personal prayer, even a purification of the self in preparation of the final labour.

The first part of the finale is notable for the way Abbado makes the instrumental recitatives really speak. The joy theme itself enters very serenely and as it swells to forte I wondered if this movement would succeed in definitively crowning the others. But we must remember Abbado’s long experience in the opera house and he knows very well that a tempo that sounds a little slow on the orchestra may be exactly right when voices enter and have to fit words to it. And so it proves. As the tenor launches into the theme we are in a world of transparent light-heartedness not far removed from the “Magic Flute” and from then onwards we never look back. Abbado manages the numerous tempo changes as naturally as I have ever heard, giving gravity to the slower portions without undue weight. The final solo quartet is faster than usual and makes sense for once, the soprano actually sounding at ease in the concluding ascent. I think that what I like about this performance is that Abbado invites you to share his joy but does not browbeat you into being joyful whether you like it or not, always the danger with a more massive performance.

In its search for textural clarification, in its rejection of both Teutonic weight (à la Klemperer) and apocalyptic drama (à la Toscanini), this is an essentially modern performance. It is also a profoundly religious one. If I wanted to summarize the programme suggested by the four movements, it might be something like “Pain – futility – prayer – fulfilment”. It is certainly not a very Germanic overview, but Beethoven is big enough to take a range of interpretations. It is, I would say, an deeply Italian conception. Not the Italy of spaghetti and football finals, or even of Verdi, but linking back to the intensely humanized religious dramas of such painters as Tintoretto and above all Caravaggio.

This is, I think, one of the great Ninths on record. There could never be consensus on the “best version” and no one should limit himself to just one. I hope my description will help you decide if this one is for you. It will be particularly welcomed, I would say, by anyone who feels that Beethoven is excessively preachy in this symphony. Maybe they will find Abbado’s vision one they can share.

Christopher Howell

Help us financially by purchasing from