Music in Exile – The Twentieth Anniversary of the ARC Ensemble

by Rob Barnett

There’s often a worthwhile story to be told behind a self-proclaimed series on a record label. At the heart of each there is a burning enthusiasm and commitment coupled with risk and funding. These factors, inimical and beneficent, keep morphing – smiling and grimacing. As an example, Chandos have over their many meritorious and often brilliant years had more than a few. The passionate convictions of composer and executant societies, authors and artists have played their parts.

So it has proved with the ARC Ensemble’s Music in Exile series for Chandos which, in its own sweet way, can be related to Naxos’s Milken Archive and, perhaps more appositely, to Decca-Universal’s flagship from the 1990s the discs from Entartete-Musik (the latter really should be gathered into a single boxed edition). Of ARC’s Music in Exile series there are now six discs and a seventh impending. The series owes its musicianly existence to an adaptable ensemble: the ARC Ensemble Canada. The series has as its objective the recording of the music of “composers primarily from the post-1933 period when politics and racism as practised by the Nazis, Stalin and other repressive regimes forced artists to flee Europe and to seek refuge all over the world.”

The group’s first major success predated the Chandos connection with its Music Reborn sequence which featured composers who had been killed during the Holocaust. A few years later, Simon Wynberg programmed a weekend dedicated to the works of émigré composers like Erich Korngold and Miklós Rózsa, musicians who had fled Europe during the 1930s and found sanctuary in America and the U.K. As he examined the exile experience more deeply, he very soon concluded that “dozens of composers of the period still remained unresearched, unassessed and ignored.” The ARC Ensemble had found its raison d’être and the Music in Exile series was born.

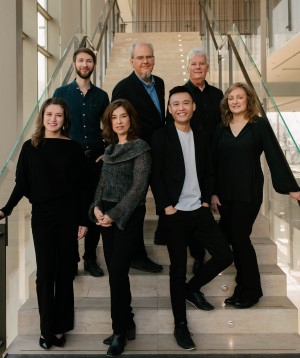

ARC Ensemble Canada, based in Toronto, draws its personnel from the senior faculty of The Royal Conservatory Canada’s Glenn Gould School, with guests cogently drawn from hither and yon. Practically, ARC and its guiding light Simon Wynberg faced adversity that in other hands would have spelled the atomisation of such a project before it limped from the blocks. Unsurprisingly given this remit, many of the composers’ archives and catalogues of these composers were shattered, their works unpublished, performing materials, where they existed, destroyed in bombing or bombardment. The Chandos discs that have emerged over the last five years (see links to reviews at end) are testimony to determination and practical toil. The end result is a growing legacy that in its own way parallels legacies from vinyl days: such as Karl Krueger’s Society for the Promotion of the American Musical Heritage, the American Record Society and Richard Itter’s Lyrita bequeathings both from BBC broadcasts and elite commercial discs. Driven by research, the practicalities of music and performing materials preparation and performance and recording the ARC have exerted themselves exceptionally in raising into the light composers either unheard of or unrecorded.

The value of Chandos’s efforts is amplified by the fact that unlike some composers who followed the same path such as Gál, Wellesz and Gerhard who had their efforts paid court by Avie, CPO and Chandos, others have had less favourable treatment. ARC deserves battle honours for focusing on those people not because of the adversity or national and religious qualities but because of their music.

The Ensemble’s Artistic Director Simon Wynberg created the Music in Exile series. He is as ARC recount “a forensic musicologist, a detective tracking down possible candidates for the Music in Exile series from a mention in a biography, an old concert program, or a suggestion from colleagues interested in this area. ….. I’ve always been drawn to the unfamiliar and I’m always curious as to why some works are endlessly performed, while others are consigned to an eternal hibernation. I love the idea of having an audience experience new music—especially music that enjoyed success in its own time—in the knowledge that we are embarking on an utterly new journey.”

He says: “Paradoxically, almost all the music the ARC Ensemble has recorded thus far has been hiding in plain sight: the archives of the New York Public Library for example, or the music library of Indiana’s School of Music in Bloomington. To talk about “discovery” is stretching what we do. Very little of it exists on tape or record, the bulk of the material survives in manuscript, and, occasionally, in published form. The process follows a fairly predictable course. I research a potential subject, track down the archive (sometimes that works the other way round) order scans (or visit the library and take photographs), and then assemble the ensemble (and recently keen music students) to read them. Repertoire choice in terms of the overall program, for a recording or concert, is left to me, but every work has to have enthusiastic support from its players.”

He continues, and in doing so tackles a paradox which this writer sums up by claiming that good music can be written by bad people and that bad music can be written by good people. Leave aside that there can be debate at different points in history about what is good and what is bad. “Yes, we have kissed a lot of frogs before finding our princes (usually princes rather than princesses) ….To quote the dreadful Donald Rumsfeld, our work involved the unknown unknowns rather than the known unknowns. I’ve gradually come to realise that many “peripheral” composers have their circle of champions. My fascination with the exile community begins with the circumstances that led to obscurity. It seems more than a little unfair that we continue the work begun by National Socialism; so many musical émigrés had so little time or opportunity to re-establish their careers. I’m sure there were talented NSDP members whose music has been sidelined by their affiliations – Webern hasn’t suffered at all for his – but their revival would travel a bumpy road.”

When Delius set the words of James Elroy Flecker for his music for Hassan he had the choir crying out about “A paradox in paradise” and so is the predicament squared up to by ARC. My favourite illustration/parable, and it is a rather tired and leaky one now, is this. Imagine you are in a car on a long journey. You turn on classical radio and hear an orchestral piece that captivates you utterly and leaves you at times in tears such is its power. Later the work is announced and you discover that it was written by a composer whose evil beliefs, criminal conduct, cowardice, complicity in the ways of the evil in power and generally contemptible behaviour you abhor. Has your experience in listening to this music, and reacting as you did, been obliterated by this discovery?

ARC seems practically to have squared the circle of elevating all music written by all such composers as worthy of revival. Just because composers emerge from such a milieu and history their music is not automatically worthy of being heard now. Old truths about bad or evil human beings able to write good music and the oppressed and refugees being able to perpetrate dull music has surely been well learnt by ARC. Bad people can write good music and bad and dullard music can be written by the virtuous, hard-pressed and persecuted. It’s a tough lesson to imbibe and is perhaps an extension of those old-fashioned biogs of the great composers which were re-wrought and bowdlerised so that their subjects come across as fragrant plaster saints. Humans are greater – and lesser – than this. The music’s the thing.

In resurrecting music forgotten in the boxes of library archives, the ARC Ensemble has created renewed appreciation for a growing list of gifted composers: for example, the Ukrainian nationalist Dmitri Klebanov, who was suppressed under Stalin; the Sephardic composer and musicologist Alberto Hemsi, who fled Turkey and Egypt to settle in Paris; and Walter Kaufmann, who found sanctuary in Bombay and created a uniquely personal language by fusing Indian and Western traditions. As a direct result of ARC’s research and recording, Kaufmann’s works are now published by the publisher Doblinger, and both European and American orchestras are now programming his works. Kaufmann’s Indian Symphony will be reintroduced to an audience at Carnegie Hall in November this year.

Every one of the exiled composers that ARC has smiled upon has both a compelling story of flight and exile, and a body of music of extraordinary range and quality. “It is hugely exciting to uncover a piece that quickens the pulse the first time you hear it,” says Wynberg, “But the process is also rather nerve-racking as we are always asking audiences to trust our choices in travelling these unexplored paths.”

Wynberg acknowledges that while the canonic repertoire is secure, he is confident that the new platforms for distribution and the explosion of social media, will encourage listeners to leap into the unknown. “When ARC performed a Klebanov String Quartet for NPR’s Tiny Desk”, Wynberg reports, “I watched in disbelief as the number of views exploded. The YouTube channel alone quickly exceeded 50,000…Videos like these do suggest that there is a parallel audience for classical music that is quite separate from that of the traditional concert-goer.” (See this YouTube playlist for performances by ARC of works in the series)

The shining path still shines for Wynberg, ARC and Chandos. Their next disc waits in the wings. It is a recording of premieres of scores by Robert Müller-Hartmann (1884-1950) who left Hamburg with his wife in 1937 and settled in England. A friend of RVW, Müller-Hartmann died in one of the English composer’s most cherished haunts, Dorking. His worklist includes a Symphony (1927), an overture, a set of variations, a Sinfonietta (1943) and Craigelly Suite (1944). He translated, into German, a large part of RVW’s A Pilgrim’s Progress.

Wynberg added in conclusion: “It’s important to know that in many cases, we are exploring a small fraction of a composer’s output. We don’t have the forces to perform larger chamber works, orchestral pieces or opera. And generally, vocal music is not included on recordings although I do try to feature it in concerts. So there is a wealth of repertoire that awaits exploration. I would love our recordings to serve as introductions. …. I am convinced that we have inherited a distorted idea of the twentieth century’s repertoire, both through the re-recording of what are now “standards” and as a result of the various currents of fashion that moved through academies and pushed so many traditionalists onto the shore.”

Rob Barnett

MusicWeb International reviews of ARC Ensemble recordings

Jerzy Fitelberg (Chandos): review ~ review

Paul Ben-Haim (Chandos): review ~ review

Alberto Hemsi (Chandos): review ~ review

Szymon Laks (Chandos): review ~ review

Walter Kaufmann (Chandos): review ~ review

Dmitri Lvovich Klebanov (Chandos): review