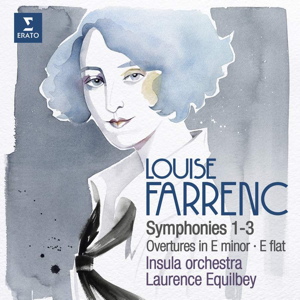

Louise Farrenc (1804-1875)

Symphony no. 1 in C minor, op. 32 (1841)

Symphony no. 3 in G minor, op. 36 (1849)

Symphony no. 2 in D, op. 35 (1845)

Ouverture no. 1 in E minor, op. 23 (1834)

Ouverture no. 2 in E flat, op. 24 (1834)

Insula Orchestra/Laurence Equilbey

rec. 2021/22, Boulogne-Billancourt, France

Erato 5419752210 [2 CDs: 113]

Nowadays, it seems you can barely move for female composers, which is a surprising and rather wonderful thing to be able to say. Of course it wasn’t always like that; in the 19th century (and even more before it), women had the greatest difficulty in getting their music taken at all seriously, let alone performed by reputable artists. Which makes it all the more remarkable to see how many talented female composers of that era are now emerging from obscurity and having their works performed and recorded.

Louise Farrenc was born in Paris in 1804 as Jeanne-Louise Dumont. Her parents were both successful sculptors, and the family was full of distinguished figures in the visual arts. She was a true child prodigy, and entered the Paris Conservatoire at the age of fifteen to study orchestration and composition. She was also an excellent pianist, so it’s not surprising that a large proportion of her output is for solo piano, or for chamber groups involving piano.

In 1821, she married the flautist Aristide Farrenc, who became a successful music publisher, so enabling Louise’s piano music to become well-known around Europe – Robert Schumann wrote favourably of the Piano Variations on a Russian Melody. But the orchestral works featured on this disc – the two overtures and three symphonies of the 1830s and 40s – remained unpublished, even though they all received performances in Farrenc’s lifetime.

This is music that is characterful, skilfully composed, and well worth hearing. The influences are those you might expect; Beethoven – of course – Mendelssohn, Schubert, Weber, and a little Schumann too. Yet she has her own distinctive voice, and there are many interesting and original touches. The first symphony, for me, is the most compelling of the three works in the form. There is a clear thematic link between the material of the first and third movements, suggesting a desire on Farrenc’s part to create symphonic unity. Perhaps most striking in that regard is the opening of the second movement, Adagio. The first having ended emphatically in C minor, Farrenc begins this slow movement with a low unison G, which then leads by devious (and perhaps not entirely convincing!) means to the movement’s main key, A flat major.

But there is tremendous drive and rhythmic power in this music, with vigorous and explosive cross rhythms and climaxes. You could argue that Equilbey and her players overdo this at times; certainly the timpani are given a very high profile. But the mild looking lady who smiles gently from Rubio’s 1835 portrait (reproduced in the booklet) certainly had plenty of fire in her belly, and these performers’ passionate readings put her very much in her rightful place as an important figure in 19th century French and European music.

As the excellent booklet notes by Christin Heitmann make clear, the premiere of the 3rd Symphony in G minor in 1849 was probably Farrenc’s greatest public success. The performers were the Societé des Concerts du Conservatoire de Paris (nowadays the Paris Conservatoire Orchestra), a body famous for its conservatism. The mere fact of her symphony’s presence in a concert series largely devoted to the Austro-German classics is evidence of how seriously her talent was taken by her immediate contemporaries. Yet repeat performances of the symphonies remained rare, and they all lay unpublished for the rest of Farrenc’s life.

Disc 1 is completed by Symphony no. 3. Its opening is striking; a solo oboe is joined quietly by other woodwind, the strings answerimg with similar restraint. The stormy Allegro that follows is less memorable, despite some arresting harmonic touches. But the Adagio cantabile second movement is very beautiful, and shows Farrenc’s sensitive understanding of her orchestral resources. The clarinet in particular has some lovely lyrical moments, including the presentation of the broad main theme over quietly tapping timpani. The quality remains high for the delightful Scherzo; scurrying strings with ‘devilish’ trills at the beginning, and a calmly pastoral central trio. The finale returns to the Sturm und Dräng of the first movement, relieved by a Mendelssohnian second theme of great charm.

Disc 2 contains the two overtures, preceded by the 2nd Symphony, in which the earlier stages of the first movement demonstrate another Farrenc trait – major/minor ambiguity; it takes a while for the Allegro section to settle convincingly in the major mode. That tendency is present again in the first of the overtures, which, though described as being ‘in E minor’, begins forthrightly in E major; whereas no. 2, described as ‘in E flat’ (which would imply the major key) begins in E flat minor! These ‘ouvertures’, earlier than the symphonies, feel like preparatory exercises, competent enough (despite their eccentricities of tonality!), with brief slow introductions – in French Overture manner for no. 1 – leading to sonata form Allegros.

Before I leave disc 2, I must mention the scherzo of Symphony no. 2 (track 3), which might be the single most engaging movement of all in these symphonies. The scherzo section could easily be taken for early Dvořák, with its furiant-like duple and triple rhythms, while the trio emulates the French musette, with gentle drones and tuneful writing for woodwind and horns.

The Insula Orchestra was founded by Laurence Equilbey in 2012, and is now the resident ensemble at the new Parisian arts centre La Seine Musicale. It has arguably become, under her imaginative guidance, France’s foremost period instrument ensemble. On these discs, they play mostly with great style and aplomb; just occasionally one encounters some slightly sour intonation, as in the trio of Symphony no. 3. But it is great to hear again the nasal, reedy quality of French bassoons (so often sadly missing even in French orchestras these days), and the clarinet playing is a joy throughout. The horns are to me a little disappointing, burbling away indistinctly in the background; one longs for a brassy edge from them from time to time. I mentioned the explosive timpani -– played correctly using hard sticks when needed – and the string tone is both incisive and warmly expressive when appropriate.

This is a fine issue, and one that will take another important step towards cementing the reputation outside of France of this brave talented composer.

Gwyn Parry-Jones

Previous review: John Quinn (May 2023)

Help us financially by purchasing from