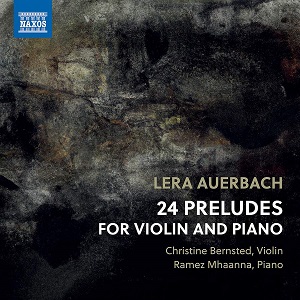

Lera Auerbach (b. 1973)

24 Preludes for Violin and Piano (1999)

Christine Bernsted (violin)

Ramez Mhaanna (piano)

rec. 2022, Royal Danish Academy of Music, Copenhagen, Denmark

Naxos 8.574464 [54]

There are already three recordings of Lera Auerbach’s 24 Preludes for Violin and Piano and a few others with selections from them. This is the most recent, while Vadim Gluzman and Angela Yoffe, dedicatees of the work, recorded it for BIS, and the Avita Duo for Hänssler. It is good to see the attention these preludes are receiving and it gives one hope they will enter the standard repertoire.

I first became acquainted with Auerbach’s music when I reviewed the disc of her piano trios back in 2018 (review). She impressed me then with her original voice that at the same time displayed the influence of her illustrious forbears, Shostakovich and Prokofiev. With this new disc I can confirm that Auerbach is a composer whose career I will surely follow and will eagerly anticipate each new recording of her music. She was born in Chelyabinsk, Russia and wrote her first opera at age 12. She visited New York City on a tour when she was 17, then defected, and has remained a resident there ever since. She studied music at Juilliard and comparative literature at Columbia University, and is not only a composer but also an author, poet, sculptor and painter—a true Renaissance figure. Auerbach debuted at Carnegie Hall in 2002, performing as pianist in her Suite for Violin, Piano, and String Orchestra with Kremerata Baltica. She has composed two further sets of 24 preludes, one for piano solo and the other for cello and piano. In the present set she follows Chopin’s example, as Andrew Mellor notes in the CD booklet, by “beginning in C major and descending through a circle of fifths via which each major key is followed by its relative minor” and thus covering all the keys. However, it is not always easy to tell which key a prelude is in, at least at the start of the prelude. There is a huge amount of variety in this work, while at the same time a unity that makes the whole greater than the sum of its parts.

These are clearly not violin preludes with piano accompaniment, since the piano has an equal role and may occasionally dominate the violin. The first prelude, marked Adagio mortale, begins rather inauspiciously with a single, repeated note in the piano’s high register and a held note in the bass, while the violin plays a haunting melody over the accompaniment. Then the violin breaks out, becoming forceful and dissonant before the prelude concludes once again with the repeated piano chords and the violin “whistling” softly. The last prelude of the entire set returns to these repeated piano chords, concluding the work quietly and eerily with a note high on the violin.

Other highlights include the tuneful and folk-like Prelude No 3 in G major, Andantino misterioso, with the violin playing the melody softly over the piano. Then No 4 in E minor is a tour-de-force for the violin, a moto perpetuo piece. No 6 in B minor is quite dissonant with irregular rhythms in the piano part, reminding me of Ligeti, while No 8 in F-sharp minor has a sad, plaintive violin theme over piano chords in ¾ time that is similar to one in Auerbach’s Piano Trio No 2. The following Prelude in E major, with pizzicato violin, sounds like some distorted version of a dance from Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet ballet. No 11 in B major, marked Allegretto, betrays the influence of Shostakovich with its catchy tune played first by the violin and then the piano. No 14 in E-flat minor, Presto, is a wild dance that is noisy and dissonant but characterful and memorable. This leads directly by means of hangover on the sustain pedal to an Adagio sognando that is in total contrast and contains a beautiful melody on the violin, again reminiscent of her Piano Trio No 2. No 16 is another Misterioso prelude with shades of Prokofiev, while the following prelude, marked Vivo, begins with a virtuosic violin part before changing completely to something mysterious by means of piano chords under a long violin note. Prelude No 20 in C minor, Tragico, is just that, with loud, dissonant piano chords answered by the violin. Later in the prelude, the dynamics quieten down and the performers play a lively tune that sounds like a children’s song, which is then parodied in a loud, distorted version of the theme. Those are only some highlights for me, as I found every prelude interesting.

The 24 Preludes is a major work that deserves the exposure this CD should help it receive. Doing a comparison with excerpts from the earlier recordings, I see little preference in one over the other. Gluzman and Yoffe are undoubtedly authoritative and their disc contains a couple of other pieces by Auerbach, as do the estimable Avita Duo. Christine Bernsted and Ramez Mhaanna, the Danish duo here, have nothing to fear from this competition and perform with all the virtuoso panache required. The sound on the Naxos CD has greater presence, being recorded more closely and enhancing the dramatic elements of the music, and the price is right. Unlike many Naxos products, this one includes a substantial booklet with Mellor’s informative note on the music, bios of the artists, a discussion by them of their duo and Auerbach’s music, and full-colour photos. In their discussion, they indicate plans to issue a recording of Auerbach’s Double Concerto for violin, piano, and orchestra. I indeed look forward to that with anticipation.

Leslie Wright

Help us financially by purchasing from