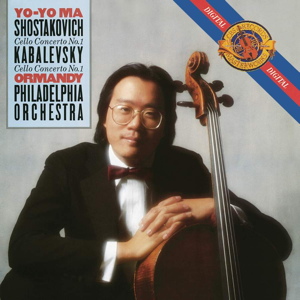

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975)

Cello Concerto No. 1 in E flat major, Op. 107 (1959)

Dmitri Kabalevsky (1904-1987)

Cello Concerto No. 1 in G minor, Op. 49 (1949)

Yo-Yo Ma (cello), Philadelphia Orchestra/Eugene Ormandy

rec. May 1982, Scottish Rite Hall, Philadelphia, USA

Presto CD

Sony 88697547272 [46]

Yo-Yo Ma was 27 when he recorded this performance of Shostakovich’s masterly concerto. It was one of the earliest on record to rival Mstislav Rostropovich, the work’s dedicatee, also on CBS and also with Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra. Ma’s performance was well received at the time in Gramophone and elsewhere, but I had not heard it before requesting this disc for review.

Rostropovich’s performance has been available in a number of guises over the years. This true classic of the gramophone should be in every Shostakovich collection. Rostropovich’s playing, in this concerto and elsewhere, was marked by formidable technical mastery alongside a kind of passion rarely encountered elsewhere. He frequently seemed almost possessed by the music he was playing, a characteristic that was as evident visually as aurally. His playing in the Shostakovich is fearless; he throws himself into the challenge. If I do not quite feel the same about Ma, I am by no means suggesting that the playing is in any way tentative. On the contrary, the work’s opening movement is characterised by a sense of urgency, with an impetuousness one might expect from a young virtuoso. The result is less playful and rather darker than is the case in many other performances.

Ma’s playing in the slow movement is beautiful, very inward and with a certain freedom of expression, especially in the second group of themes. In the celebrated duet between the soloist and the celesta, his harmonics are sepulchral in tone and atmosphere. The movement ends in extreme melancholy, almost despair, a perfect lead-in to the cadenza third movement whose opening is a voyage into the unknown. Ma brilliantly executes this remarkable meditation on several scraps of themes. He makes the most of its drama, and paces perfectly its journey from questioning uncertainty to violent testimony. The rapid rising and falling scales in the final bars seem even more cynical and pointless than usual. It is as if the composer is allowing the soloist to show off whilst at the same time making clear that showing off for its own sake achieves little. But this is, once again, the perfect lead-in to the finale. The winds are at first sardonic and later sound like a demented hurdy-gurdy. A repeated phrase from the first clarinet and rising chords in the strings add to the overall nihilistic effect that is impressively sustained as far as the final bars.

Shostakovich composed both concertos for Rostropovich, and both, though very different, are towering masterpieces. Kabalevsky’s First Concerto was composed with advanced students in mind and is less of a technical challenge. Indeed, anyone who plays a stringed instrument will appreciate the utmost skill with which Kabalevsky fashioned the virtuoso passages so as to fall under the fingers of a young player. The work is, by the same token, considerably less complex emotionally and psychologically than Shostakovich’s First.

The opening movement skips along amiably in compound time. Its second main theme is delightfully introduced by a clarinet and a flute who then go on to make comments from the sidelines. The finale is exuberant, with a folk song feel and a broad, expansive melody a couple of minutes before the end. This precedes a rapid passage which allows the soloist to show off and bring the work to an exciting close. The five-minute slow movement is the heart of the work, very beautiful and rather sombre. This concerto, which was new to me, is a thoroughly attractive and engaging work, worth twenty minutes of any music lover’s time.

Yo-Yo Ma plays Kabalevsky’s concerto with eloquent conviction. In some hands, Shostakovich’s work can be a fairly genial work. Ma gives us something more unsettling, more challenging, more subversive. The important part for the first horn is superbly delivered, and the orchestral playing under Ormandy is very fine in both works. The digitally remastered 1982 CBS analogue recording is excellent. In earlier days, when a masterpiece such as the Shostakovich concerto was new and unfamiliar, and recordings were few and far between, critics would often observe that the coupling could favour one of the few readings available. Few, perhaps, would have found Kabalevsky’s piece particularly enticing, but for me it was a delightful discovery. Ma’s Shostakovich account is a revelation, a towering performance that more than earns its place amongst other fine performances – Heinrich Schiff, Truls Mørk, for instance – on my shelves.

William Hedley

Help us financially by purchasing from