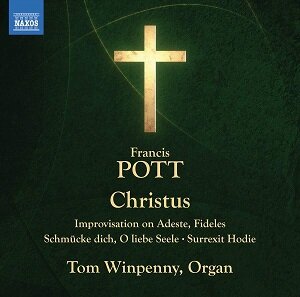

Francis Pott (b. 1957)

Improvisation on Adeste, Fidelis (2005)

Christus – Passion symphony for organ (1986-1990)

Schmücke dich, O liebe Seele (2013)

Surrexit Hodie (Fantasia-Toccata sopra ‘O Filli et Filliae’) (2019)

Tom Winpenny (organ)

rec. 2020, The Cathedral and Abbey Church of St Alban, St Alans, UK

Naxos 8.574252-53 [2 CDs: 141]

Francis Pott’s organ symphony, Christus is on a vast scale. It’s cast in five movements, the first and last of which play for over 32 minutes and 38 minutes respectively in this performance. The musical score is so enormous that United Music Publishing has divided it into no fewer than three volumes, with those two outer movements published as Vol 1 and Vol 3.

Remarkably, given the sheer scale of the work and the colossal technical and intellectual demands that it makes on the organist, this is the third recording. I first encountered it through the astonishing 1997 recording by Jeremy Filsell, issued by Signum (review). Subsequently, I heard the first recording, released by Priory (PRCD 390). That recording, by Iain Simcock, was made at the first performance of Christus, given in Westminster Cathedral in April 1991. Both the Filsell and Simcock recordings were made live; Tom Winpenny is the first organist who’s had the luxury of setting down a recording under studio conditions.

I will start with a disclaimer and say that I don’t propose to make detailed comparisons between these three recordings; the sheer scale of such an enterprise would be as daunting for the reader as it would be for me: I know my limitations! In any case, to the best of my knowledge the Simcock recording is no longer available. I will content myself with just one or two general remarks about how the two earlier recordings compare with this newcomer.

As I said, the Priory recording was made in Westminster Cathedral, a building with a vast acoustic. It must have been the devil’s own job to capture the sound of the cathedral organ, particularly given that an audience was present. The Westminster organ is recorded rather less closely than is the case on either the Filsell or Winpenny recordings. As a result, to my ears the instrument doesn’t have quite the impact that one experiences from Filsell and Winpenny in such passages as the tumultuous opening of the fifth movement. Hushed passages can sound rather distant by comparison with Simcock’s rivals, but one could argue plausibly that his recording thereby achieves a sense of extra mystery.

In a work of this magnitude timings are something of an irrelevance, possibly an impertinence. For what it’s worth, though, Winpenny’s performance plays for 120:28 and Filsell brings the work home in 125:52. Simcock is more spacious: his recording plays for 139:06 but I think it’s important to note that in his performance Iain Simcock was founding the performance tradition of Christus. One differentiator between the Filsell traversal and those of his colleagues is that Signum Classics divide the movements into short tracks – there are 45 in all across the two discs. That can be helpful in keeping the listener on track – I certainly found it valuable when writing my review of the Filsell performance. A key advantage that Tom Winpenny has is that his is the only recording to include other music; he offers the opportunity to hear three more organ works by Francis Pott. But enough of “comparisons”. The points I’ve made above are fairly trivial – though they might give someone who already has either the Filsell or Simcock recording some indication of whether or not they should additionally invest in the Winpenny version. One point that is far from trivial, however, is to salute all three organists for their courage and virtuosity in taking on and mastering Pott s hugely challenging musical structure.

All three releases have benefitted from excellent booklet essays by the composer. In giving a very brief outline of the work I will draw to some extent, with acknowledgement, on what he has said. As I mentioned, the symphony is divided into five substantial movements: I ‘Logos’; II ‘Gethsemane’; III Passacaglia (‘Via Crucis’) – Scherzo – ‘Golgotha’; IV ‘Viaticum’; V ‘Resurrectio’. Each of the five movements is headed up by superscriptions. These include some lines by Thomas Traherne and verses from a number of scriptural sources (Movement I); verses from a poem by Thomas Merton (1915-1968) (II); ‘I am the great sun’, a poem by Charles Causley (1917-2003) and some lines from the 12th Century Irish text The Speckled Book in an English translation by Howard Mumford Jones (III); lines by St John of the Cross and Dylan Thomas (IV); and a verse from the prophet Joel (V). Helpfully, Naxos include all these texts in the booklet. Francis Pott writes in the Naxos booklet: “Respectively, the five movements trace the Coming of Christ; Gethsemane; Via Crucis/Golgotha/the Deposition; the Tomb; and finally, Resurrection – portrayed not as victory already attained, but as a vast struggle towards ultimate triumph”. A number of thematic motifs run through the score, including a chorale and a ‘motto’ consisting of the notes D-E-C#-F, though I think I’m right in saying that the motto appears at other pitches during the work.

In the composer’s words, the first movement, ‘Logos’ evokes “a world as yet devoid of any affirmative or elevating impulse”. Here, I think he’s particularly referring to the opening; if it’s not presumptuous of me to say so, I think this equates to what one would traditionally think of as the slow introduction to a symphony’s opening movement. The opening pages contain quiet, spare-textured music that gives the impression of uncertain searching. Gradually, the tempo seems to pick up (though perhaps the pulse may remain fairly constant) until a huge climax is achieved at around 9:30. After this, what I might term the main allegro commences; here the mood seems brighter, a little less unsettled. The music that follows requires considerable virtuosity on the part of the organist – and sustained concertation over a long time span. Tom Winpenny is terrific at maintaining momentum; equally, he successfully retains the listener’s concentration in the passages where, occasionally, the music pauses for breath and reflection. The last five minutes or so are thrilling, both in terms of the music itself and also the sounds that Winpenny conjures from the St Alban’s organ. It must be a daunting – but probably exciting – thought for any organist that after delivering this enormous and challenging movement there’s still about 90 minutes of playing in prospect.

The second movement, ‘Gethsemane’ is mostly subdued. Listening, I get a real sense of the apprehension and isolation of Christ in the garden, knowing his Passion is imminent. In my review of the Filsell recording I described the music as “intense, even oppressive”; I haven’t changed that view. The sheer technical virtuosity required in the first movement is not needed here but instead the organist needs concentration and sensitivity, qualities that Tom Winpenny displays in abundance.

The tri-fold third movement begins with a passacaglia entitled ‘Via Crucis’. I learned from the notes that in the passacaglia the ground is played 15 times, though the pitch gradually moves upwards. As the passacaglia evolves, the music grows in complexity and volume. There’s a gradual increase in urgency until the Scherzo begins (around 5:03, I think). Here, the music is jagged and aggressive; there’s power and malevolence. Winpenny brings great rhythmic energy to this episode. Beginning at 8:48 there’s a remarkable section where, in the composer’s words, “three abruptly recessed quiet passages occur, marking the arrival at Golgotha and each followed by related and dissonant outbursts symbolising the hammered nails”. The third of those outbursts leads to the central climax of the whole work; there’s no other word to describe that climax other than brutal. Eventually, the movement achieves a quiet ending, which I speculated in my review of the Filsell recording, might represent Christ’s words ‘It is accomplished’.

The fourth movement is entitled ‘Viaticum’, which Pott translates as ‘wages for a journey’. In the Roman Catholic church, it’s the term used for Holy Communion as part of the Last Rites. Let me quote my reaction to the movement as expressed in my review of the Filsell performance: “It seems to me to conjure up the Great Stillness over the world that Christians associate with the period of the entombment of Christ. Does it also, perhaps, seek to convey the feelings of loss and fear experienced by the disciples during those days?”. Slow, subdued and thoughtful music provides an important oasis of reflection after the awful drama of the Crucifixion and before the remarkable finale.

If a 32-minute opening movement seemed vast, the final movement, ‘Resurrectio’ is even more daring in scale and reach. In Tom Winpenny’s performance, this final movement plays for 38:26 (the Iain Simcock traversal takes an astonishing 43:10). You may get an idea of the complexity and ambition of this movement if I tell you that in the booklet Francis Pott’s discussion of the first four movements runs to five paragraphs; he needs no less than four paragraphs to explain the contents of ‘Resurrectio’! The movement opens with music of volcanic energy. This announces a movement of huge complexity in which, inter alia, elements of the preceding movements are recalled. It is a compositional and performative tour de force and I don’t think anyone should underestimate the sheer physical demands that this movement must place on the organist. For one thing, the virtuosity requirement is relentless; in addition, the performer dare not lose focus for even a moment. Though much of the music is toccata-like and driven, not everything is tumultuous; there is a calmer episode about halfway through which then gives way to an extended, spidery fugue. At 26:46 the music bursts back into vehement life and the composer describes part of what follows as ‘War in Heaven’. The last five minutes or so are awesome in the true sense of the word. After a majestic apotheosis of the chorale theme, the symphony comes to an end on a huge chord of F# major, which the player is encouraged to hold for a long time – here, it’s sustained for a full twenty seconds. Tom Winpenny’s playing throughout the whole duration of Christus is magnificent in every respect but I’m blown away by his account of this immense final movement. The recording was made in the presence of the composer and I’m sure he was thrilled by what he heard. Christus is an amazing composition and Tom Winpenny brings it vividly to life; he makes the music fairly leap off the page, even when the dynamics are subdued.

As a significant bonus, Tom Winpenny plays three shorter pieces – though I’d strongly advise listening to them separately: one really doesn’t want any other music before or after the symphony. Two of the pieces here receive their first recordings. One is Schmücke dich, O liebe Seele. This is Francis Pott’s contribution to the Orgelbüchlein Project in which organist William Whitehead invited composers of today to write short pieces to “fill in the gaps” which Bach left in his Orgelbüchlein, leaving to posterity only the titles of Chorale Preludes which he planned to write. Pott’s piece is a tranquil meditation on the chorale melody in which I believe he successfully invokes the spirit of Bach but, of course, with a contemporary slant. The other recorded premiere is Surrexit Hodie (Fantasia-Toccata sopra ‘O Filli et Filliae’) This is an Easter Sunday recessional, commissioned in 2019 by Marko Sever who was at that time Organ Scholar of St Alban’s Cathedral. I presume, therefore, that the music was first played on the very organ upon which Tom Winpenny now plays it. As befits the occasion for which it was conceived, the piece is mostly jubilant in tone.

Improvisation on Adeste, Fidelis is not new to CD; I know of at least one other recording, played on the organ of the chapel of King’s College, Cambridge (review). I knew that Francis Pott wrote it as the closing voluntary for the Festival of Nine Lessons and Carols in 2005. What I didn’t know until I read it in the booklet was that in 2005 the Organ Scholar at King’s was none other than Tom Winpenny. The piece was written for him and he premiered it. It’s good that he has now had the opportunity to record it. It’s a super, ebullient piece. The music is peppered with references to the hymn tune until at 3:40 the melody is revealed in full on the pedals, festally decorated by busy figurations on the manuals.

This is a notable release. All the music is thrilling and deeply felt and Tom Winpenny performs it all superbly. Goodness knows how long it took him to learn Christus; it must have been a formidable undertaking and his recording of it is also formidable. He’s been the Assistant Master of Music at St Albans since September 2008 and, clearly, he knows the Abbey’s organ inside out. His performance brings out all the subtle nuances and dramatic peaks of Francis Pott’s immense score.

The recording was produced and engineered by Mark Hartt-Palmer of Willowhayne Records. It must have been a great challenge to record this music with its huge range of dynamic contrasts and to translate the performances for domestic listening. I’d say he’s succeeded triumphantly: the sound has presence, impact and clarity.

This CD set is a splendid achievement by organist, composer and recording engineer.

John Quinn

Help us financially by purchasing from