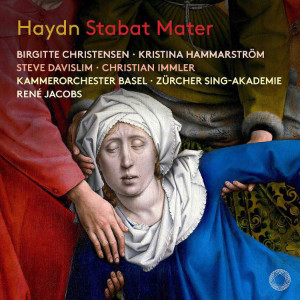

Joseph Haydn (1732-1809)

Stabat Mater (1767, enlarged wind orchestration version by Sigismund Neukomm, 1803)

Birgitte Christensen (soprano), Kristina Hammarström (alto), Steve Davislim (tenor), Christian Immler (bass)

Zürcher Sing-Akademie

Kammerorchester Basel/René Jacobs

rec. 2021, Paul Sacher Saal, Don Bosco, Basel, Switzerland.

Sung Latin texts with rhymed English and German translations enclosed.

Reviewed as download from press preview

Pentatone PTC5186953 [61]

While Joseph Haydn is often called the Father of the String Quartet (rightly) and Father of the Symphony (somewhat questionably), he himself had reservations about his contribution to sacred choral music. He once stated that his younger brother Michael produced finer music in this genre. Indeed, though Michael Haydn’s best masses and requiems are still well regarded (and represented by a number of excellent recordings), the elder Haydn was given a late-in-life chance to rival his brother’s production. The great masses he created to celebrate the name day of the wife of his employer, Nicholaus Esterházy II, are perhaps Joseph’s finest contribution to choral music, even considering his two great oratorios. That might be a minority opinion, but here stand I.

Before these masterworks from the turn of the nineteenth century, the most imposing sacred choral music that Haydn produced are probably the Missa Cellensis (Mariazellermesse) of 1782 and the Stabat Mater of 1767. The latter was not only his most significant piece of sacred choral music up to the last great masses but also his most performed. As the notes to the current recording tell us, the piece appeared on programs not only in Austria but in Germany, Italy, and France, where it “became something of a repertory work” at the Concerts Spirituels in Paris. Scores of the work were published in France (twice), England, and Germany.

Haydn modeled his Stabat Mater on the most famous version of the day, that by Giovanni Baptista Pergolesi (1736). Like Pergolesi’s piece, Haydn’s is restrained, scored as it is for strings, oboes (doubling English horn), and organ. Perhaps because this was Haydn’s first important foray into sacred music, he sent the score for appraisal to Johann Hasse, at the time court conductor at Dresden and author of much highly regarded choral music. Hasse’s reaction was positive, to the extent that the German composer invited Haydn to perform the work in Vienna, which he did.

Eliciting Hasse’s opinion made sense for a young and pretty much unknown composer. And while Haydn’s piece is individual and very accomplished, I think it may show some influences of the older composer. At least that’s my reaction after listening again to Hasse’s fine Requiem in C Major (1763). Be that as it may, Haydn’s Stabat Mater found an audience far beyond Vienna, finally rivalling Pergolesi’s beloved work in popularity.

A bit of historical perspective: the poem that provides the text of the Stabat Mater dates from the thirteenth century and probably reflects the medieval reverence for Mary that the troubadours expressed in their lyrics and that the Church itself later embraced. The Council of Trent, in its reform efforts, suppressed the Stabat Mater though it was reinstated to the liturgy in the eighteenth century shortly before Pergolesi’s setting of the text. It is a fairly sophisticated poem in 20 stanzas built on triplets with an interlocking rhyme scheme (AAB CCB….). The work reflects the grief of Mary at the foot of the Cross but broadens its perspective to include a prayer by the speaker in hopes that respect for Christ and his sacrifice will translate to salvation at the Day of Judgment.

Haydn set the poem as a series of 14 movements, mostly slow and reflective, though a couple of them are fiery, almost militant, as the speaker reacts to the injustice of Christ’s death. The final number, in which the speaker hopes for an afterlife in paradise, is a choral fugue with solo interjections, including ecstatic melisma passages sung by the soprano.

In 1803, Haydn revisited the still-popular Stabat Mater, commissioning his apprentice Sigismund Neukomm to reorchestrate the work. Under Haydn’s direction, Neukomm added a panoply of wind instruments and percussion: a flute and pairs of clarinets, bassoons, horns, trumpets, and trombones, plus timpani. The effect was to turn Haydn’s motet into a mini oratorio. This was a sign of the times: Mozart had reworked the instrumentation of Handel’s Messiah to make it more appealing to late-eighteenth-century audiences, and later Mendelssohn would do the same for Israel in Egypt. Not to mention that the updated version of the Stabat Mater appeared around the same time as The Mount of Olives, an equally compact oratorio composed by Haydn’s former pupil Ludwig van Beethoven. (Sigismund Neukomm, by the way, is interesting in his own right. He was a much-performed composer in his day who worked for a while in, of all places, Rio de Janeiro, where he helped popularize the works of Haydn and Mozart.)

Neukomm’s orchestration adds many coloristic effects, of course, but they are mostly subtle and restrained. The added woodwinds lend a plaintive quality to the long first movement of the piece, while the trombones add a sepulchral note to the final measures. In the third number, they add an air of gravitas as well as a certain majesty. So do the horns in the tenth number, in which the speaker prays that he (or she) will always take Christ’s sacrifice to heart.

Trumpets and drums make their appearance in the fifth and eleventh numbers, wherein the bass describes in turn the suffering of Christ and the fires of hell, from which he hopes Mary will protect him. These instruments return in the triumphal final number reflecting the speaker’s hope for personal resurrection.

I’m not aware of another recording of the Haydn/Neukomm version of the Stabat Mater, so I can’t make a direct comparison. I did refresh my memory of J. Owen Burdick’s well-received recording of Haydn’s original version on the Naxos label. This is a fine performance featuring the REBEL Baroque Orchestra and Trinity Choir, who have recorded all of Haydn’s masses for Naxos. Burdick’s soloists are good as well, but they really can’t match the virtuoso team that René Jacobs has assembled for his recording. Maybe it’s the extra heft that the brass provides in the numbers with bass solo, but Christian Immler really shines in these movements. Special mention as well for soprano Birgitte Christensen, who brings both welcome shade and light to the numbers she’s featured in. Kammerorchester Basel prove sensitive accompanists and appropriately subtle colorists.

Jacobs may be a controversial conductor, especially in Mozart, but I find his Handel and Haydn exemplary. His recordings of Handel’s Saul and Haydn’s The Seasons are my favorite versions of those works. Jacobs responds with equal sensitivity to Haydn’s more intimate Stabat Mater setting.

I listened to the recording as a high-quality download and was mostly quite pleased with the results. While I would prefer a slightly more resonant acoustic, the impact and detail that the engineers achieve are admirable. I’m sure that from now on, this will be the version of Haydn’s masterwork I return to most often.

Lee Passarella

Previous review: Göran Forsling (April 2023)

Help us financially by purchasing from