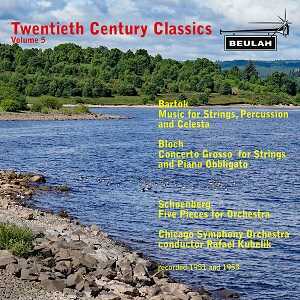

Twentieth Century Classics Volume 5

Béla Bartók (1881-1945)

Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta

Ernst Bloch (1885-1977)

Concerto Grosso for Strings and Piano Obbligato

Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951)

Five Pieces for Orchestra Op16

Chicago Symphony Orchestra/Rafael Kubelík

rec 1951 (Bartók, Bloch) 1953 (Schoenberg)

Reviewed as a digital download from a press preview

BEULAH 5PDR20 [70]

It would seem inevitable that a label like Beulah was going to be drawn to the classic recordings from the Mercury label which have a claim to be some of the finest of the LP era. The selection of works on this new Beulah release straddles two different Mercury LPs and it demonstrates just how adventurous their recorded repertoire could be.

At the recommendation of a recent review by my colleague here at MWI, Lee Denham, I have been relishing Kubelík’s BPO collection of lumps of orchestral Wagner. With the release of a number of live Mahler recordings, the image of Kubelík as a soft-centred Mahlerian is being revised. As a conductor he tended to be eclipsed by noisier, more headline grabbing maestros like Solti and Karajan. Kubelík’s reputation has risen steadily as those of those two superstars has set.

Kubelík, a composer himself, had a fine pedigree in the music of his century, a fact sometimes obscured by his recorded legacy being dominated by nineteenth century composers. The casual listener will not be surprised at how good his Mozart with Curzon or his Beethoven with Serkin is but may be surprised to learn just how good a foil he provided for Alfred Brendel in Schoenberg’s thorny piano concerto. It is worth pointing out that the story goes that he was forced out of the Chicago job on account of performing too many modern scores.

An interesting point of comparison is between this Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta and the more celebrated later recording with the same orchestra by Fritz Reiner. They could hardly be more different. Reiner, the Hungarian, is more hard edged, rhythms driven and ensemble so sharp you could cut yourself on it. The Czech, Kubelík, is more concerned with atmosphere and sounds the more Hungarian of the two. An oversimplification admittedly but there is something in seeing Reiner as the modernist and Kubelík as sticking closely to the folk music roots of this music. Reiner’s is, rightfully, considered one of the greatest recordings of all time but the surprise is how little ground this Kubelík version has to concede to it.

In the opening fugue, Reiner maintains a terrifying level of tension that threatens to snap under the pressure the great Hungarian conductor puts it under. The tension in the Kubelík is scarcely any less intense but it is different, looser and more free with, consequently a riper string sound than Reiner’s tightly drawn strings. The advantage seems to tilt toward Reiner with the second movement where the definition of the rhythms is electric. Kubelík can’t match Reiner in terms of sheer vigour but as the movement proceeds the powerful, uncanny mood that lurks behind the rhythms makes its presence felt. The same point could be made about the finale. Reiner drives the music very hard where Kubelík’s more relaxed manner allows him to point the dance elements of the movement with greater subtlety and variety. His account has a sense of play and wit that is unusual in this movement which is generally as grim as a dance with the devil.

Kubelík’s way with the third movement adagio is fantastic in the best sense of the word – full of ripe fantasy and that essential strangeness that all the best Bartók performances have. Reiner’s will always be top of any list of great versions of this work but the much less known Kubelík fully merits a place alongside it.

Reiner’s version enjoyed especially vivid recorded sound but Mercury also knew a thing or two about sonic impact and the sound on this new version is fantastic. Indeed, I would go so far as to say that this is one of the finest issues Beulah have yet put out – a splendid way to mark the label’s thirtieth anniversary.

The Bartók is positively populist compared to the other two works that make up the programme. The Bloch is a real rarity. Written in 1925, it has suffered the neglect that has been the fate of a lot of the then fashionable taste for the neoclassical. It is a likeable, warm hearted work.

Kubelík always had a special way of coaxing a unique sound from the strings and he is at his wizardly best in the Bloch. What could be dull slabs of string chord work resonate with trenchant intensity, each part clearly audible yet seamlessly integrated. One gets so used to hearing a thinnish, sharply drawn, precisely etched string sound from the Chicago Symphony under Reiner and Solti even in Bruckner that it is hard sometimes to remember that this is the same band.

Beulah save the best for last with an absolutely stupefyingly good version of the Schoenberg Op16. This work represents in many ways one of the high points of the composer’s expressionist phase before the development of the 12 tone system. It was also born out of a time of personal troubles and this is reflected in the highly febrile mood of the pieces. Those psychological tensions are caught in orchestration of the highest sophistication and imagination. In his review of Kubelík conducting Wagner, Lee Denham pointed out the diversity of colour in the performances and the same point could be made here. Twelve tone music is, unfairly, seen as drab and grey with that notion often extended to the entirety of Schoenberg’s output whether 12 tone or not. Even in the good but necessarily limited sound of this 1953 recording, the colours glow in all their menacing wonder. The way Kubelík maintains the febrile climate across five very different pieces is a remarkable achievement and the precision of the playing matches him at every step.

It is often the case that recordings that always sounded good respond best to attempts at sonic restoration and so it is here. Mercury were always an audiophile label and the results of their approach sound surprisingly modern to my ears. Beulah’s love affair with this classic era of the LP continues with this release. For all the famously stated desire to capture the ‘living presence’ of the orchestra what I hear is the experience of listening to an album on a turntable with everything possible being done to maximise that experience. Given this view of these albums, Beulah’s methods seem particularly appropriate. They never pursue, for example, cleanness or clarity of sound for its own sake but pursue a particular aesthetic. It isn’t the only way to restore older recordings. It may well be that, for me at least, there is an element of nostalgia- a peculiar concept to apply to music as troubling as Schoenberg’s Op16! I am nowhere near old enough to have been familiar with these recordings in their original LP incarnations and I like to think that my love of them is affection for a golden era of recording rather than a hankering after the past – despite ongoing economic woes the classical recording industry remains today, miraculously, in fine health!

These recordings were released by Decca as recently as 2021 as part of their The Mercury Masters box set. There is very little to choose between the two – Decca have set about cleaning up the sound more thoroughly, Beulah understand that often the magic of a recording lurks in the scuffs and crackles. Beulah’s is cheaper but comes without notes whereas the Decca box is beautifully presented with original artwork and a lavish presentation. I am an unabashed fan of the Beulah approach so I will plump for them. Besides I already own too many lavishly presented box sets! Whatever you do though, do have a listen to these stunning performances.

David McDade

Availability: QOBUZ