Déjà Review: this review was first published in April 2009 and the recording is still available.

Franz Schubert (1797-1828)

Lieder

Elizabeth Watts (soprano)

Roger Vignoles (piano)

rec. 2008, Potton Hall, UK

RCA 88697 329322 [70]

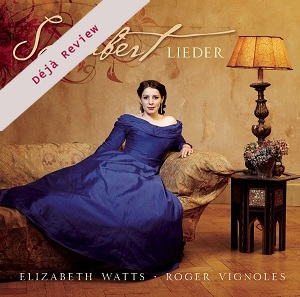

You have to go looking for the famous RCA red seal on the outside of this CD, which is a pity, as it is an attractively produced disc with an eye-catching photo of the singer on the front. Elizabeth Watts, who was born in 1979, was a student of archaeology before joining the Benjamin Britten International Opera School at the Royal College of Music in 2002. Awards and honours followed, among the most recent of which was to be selected as a BBC Radio 3 New Generation Artist. She has a wide experience of the operatic stage, and here she is now in the recital room.

She has a most pleasing soprano voice, clean and bright but without the slightest hint of shrillness. Her control of line is exemplary, her tuning faultless, and to get my one gripe out of the way now, listeners will decide if, like me, they are resistant to the extended sibilants at the quiet ends of phrases in, for example, Sei mir gegrüsst – not, in any case, my favourite Schubert song.

Miss Watts has chosen a Schubert series perfectly attuned to her vocal qualities, and perhaps, also, to her temperament. In the very first song, the well-known An den Mond, listen how subtly she reveals the difference in mood between wistful sadness as the poet invites the moon to shine down into the forest where he last saw his beloved, and the more excitable middle verses. A comparison with Elly Ameling, on Hyperion, might seem like going in at the deep end, but it is by no means disadvantageous to the younger singer, even if Ameling’s exquisite control of tempo and rubato does bring with it just a touch more pathos when the opening mood returns for the final verse. I thought Liane was new to me until I discovered it, also in Elly Ameling’s Hyperion recital. Miss Watts’ performance of this beautiful and, I believe, rather neglected song is in every way equal to that of her distinguished colleague.

The recital is an interesting mix of well-known and lesser-known Schubert songs. Die Blumensprache, for example, charmingly sung here, is a lovely song set to a poem relating how things which humans find difficult to say, sweet and gentle things as well as dark and tragic ones, are more easily communicated by flowers. This song was also new to me, but Nähe des Geliebten was not. I got to know this in the first volume of the Hyperion series, sung by Janet Baker. Hers is a more passionate performance than Elizabeth Watts’, who sees it as altogether more tranquil and reflective. Both views are equally valid, of course, and Elizabeth Watts sings the song as beautifully as she sings everything else on this lovely disc. All the same, I prefer Janet Baker’s view. The beloved, who is far away, is evoked, verse by verse, by thought (“I think of you”), by sight (“I see you”) and by the sound of his voice. The final verse, despite the lovers’ distant separation, begins “I am with you, though you are so far…” The sentiments are simple ones, simply and directly expressed in Goethe’s words. Though the song is strophic, the introduction is heard only once. Hilary Finch, in the excellent accompanying note, writes that this “magically evokes, in harmonic terms, a sense of movement from long distance to immediate presence…” Quite so. But to that let us add what Graham Johnson writes in the Hyperion booklet. “…with each change of chord we perceive the opening of a loving heart, the unfolding realisation of a deep devotion.” Schubert was eighteen when he conjured up this small miracle, which is why I prefer the youthful impetuousness of Janet Baker to the calm wisdom of Elizabeth Watts. Another beautiful performance where Elizabeth Watts finds herself in direct comparison with Baker is Heimliches Lieben, and here again it is Baker, on her Saga disc from the 1960s, who is the more enraptured.

Elizabeth Watts is masterly in Thekla, where Schiller has the ghostly voice describe what happens in the next world. No tears are shed there, and all share the same fate. Schubert’s music is cold but not indifferent, disembodied but not make-believe. It is a further example of his uncanny ability to enter into the spirit of a poem and complement it, even a poem, such as this one, to which one would have thought nothing could be added. The singer beautifully controls the long, high-lying phrases of this masterpiece. She is just as successful in The Trout, where the playful, idyllic scene becomes one of blood and death, albeit, with the composer’s impeccable understanding, contained within the limits of a little story and a little song.

She subtly evokes the inward, rather rarefied atmosphere required to summon up the poet’s feelings as he gazes on a flower in Nachtviolen. And with An die Sonne we have something quite special, an exquisite performance of an exquisite song. Dynamics are wonderfully observed and executed, intonation and breath control impeccable. In addition, Roger Vignoles accompanies with acute sensitivity, as he also does in Im Abendrot, a perfect example of the art of the master accompanist. He sticks to his singer like glue, of course, but he seems in an uncanny way to be able to anticipate what she is about to do, their music-making a true collaboration. He is totally at one with the singer, entering not only into the spirit of the composer and the song, but also into the very essence of the singer’s view of it. This is truly masterly playing.

There is not a single performance on this disc which would not solicit a favourable response from any sensitive listener. With singing of this quality, direct comparisons are irrelevant, and indeed I wonder at the usefulness of indulging in those above. Only on listening to the disc as a whole, one song after the other, does one wonder if there isn’t a certain uniformity of expression, that perhaps there is a little more characterisation to be found here and there in individual songs. But I think this is also to do with the choice of repertoire, which concentrates on the more inward, lyrical side of Schubert’s inspiration. And in any event, I don’t think listening to twenty-one Schubert songs one after the other is a good idea. Far better to pick and choose, three or four, or five, or six. Whichever of Elizabeth Watts’ performances you choose, your pleasure is guaranteed.

William Hedley

Help us financially by purchasing from

Contents

An den Mond, D193 (1815) [3.12]

Suleika I, D720 (1821) [5.25]

Im Abendrot, D799 (1825) [3.55]

Sei mir gegrüßt, D741 (1822) [4.16]

Die Forelle, D550 (1817) [2.09]

Heimliches Lieben, D922 (1827) [4.39]

Der Sänger am Felsen, D482 (18160 [3.39]

Thekla: eine Geisterstimme, D595 (1817) [5:54]

An die Sonne, D270 (1815) [3.00]

Aus “Diego Manzanares”: Ilmerine, D458 (1816) [0.57]

Nacht und Träume, D827 (1823) [4.01]

Frühlingsglaube, D686 (1820) [3:17]

Die Blumesprache, D519 (1817) [2.08]

Nähe des Geliebten, D162 (1815) [3.53]

An die Nachtigall, D497 (1816) [1.28]

Liane, D298 (1815) [3.09]

Des Mädchens Klage, D191 (1815) [3.46]

Nachtviolen, D752, [3.05]

Marie, D658 (1819), [1.50]

Lambertine, D301 (1815), [3.25]

Die Männer sind méchant, D866/3, (1828) [2.29]