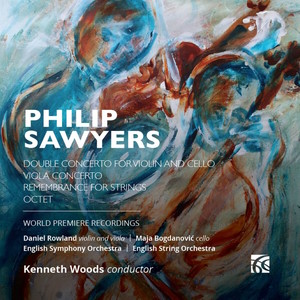

Philip Sawyers (b.1951)

Double Concerto for Violin and Cello (2020)

Remembrance for Strings (2020-21)

Concerto for Viola and Orchestra (2020)

Octet (2007)

English Symphony Orchestra / Kenneth Woods / Daniel Rowland (violin & viola) / Maja Bogdanovič (cello)

rec. 2021/22, Wyastone Concert Hall, Wales

Nimbus Alliance NI6436 [71]

This is now the sixth volume of orchestral music by Philip Sawyers on the Nimbus Alliance label and the fifth conducted by Kenneth Woods. I reviewed the first release back in October 2010 for this website here and ever since have been an enthusiastic admirer of Sawyers’ work. A brief career résumé is probably useful. On completing his training on violin and composition at London’s Guildhall School, Sawyer spent the best part of a quarter century playing in the orchestra of the Royal Opera House Covent Garden. Those years – 1973-97 – saw little time for composition. In his own words on his website in 1997 he decided to “opt for a quieter life” and left the orchestra. The quarter century since then has been far more productive in composition terms – the list of works and dates of composition can be read on the same website here. The relationship with Nimbus Alliance has been a valuable one – a quick look at that list shows that pretty much all of Sawyers’ orchestral works have been recorded by the label and in many cases quite soon after their composition. So it proves with this new disc where three of the four works date from 2020 or later and just the Octet is ‘old’ having been written in 2007.

In reviewing the Symphony No.3 recording by the same artists back in 2017 I noted; “this admiration and respect is clearly mutual and not limited to simply a professional relationship …. the close ties between performers and composer goes even further with the 3rd Symphony dedicated to conductor Kenneth Woods …. all of which points to the fact that this is a recording produced and released by a team wholly dedicated to the project – a level of commitment which is palpable throughout”. This can be echoed again with this new release which underlines the sense that Sawyers has a group of performers around him who inspire him and in turn are passionately supportive of his work. So the quality of the playing on this disc is never in doubt and indeed the evident conviction of the performers in these works has been a recurring feature of all the discs to date.

Having written a cello concerto for Maja Bogdanovič previously, in 2020 Sawyers completed his Double Concerto for Violin and Cello – which to quote the composer; “overshadowed by the famous Brahms double, this was a daunting task.” The work is in the standard fast-slow-fast three movement format, well proportioned and well balanced with a central 9:34 Andante framed by a 7:15 Allegro moderato and a closing 8:15 Allegro vivo. A feature of all Sawyers’ orchestral scores is his clear sense of instrumental colour and how to write effectively for the forces he deploys – not really that surprising given he spent a quarter century “inside” an orchestra. In the fairly brief liner note by the composer he references; “suggestions of Poulenc in his neo-Classical mode – not intentional!” Certainly the work strikes me as a whole as having a lighter spirit and a more lyrical heart than some of Sawyers’ other/earlier scores. That does not mean that there are not plenty of opportunities for virtuosic display – played here with easy flair by the excellent soloists, but there is not the same sense of conflict and resolution that inhabits some of his works. In the liner Sawyers mentions the “musical and personal connection” between the two players which I wonder is why he has written a work where the two solo parts are so intertwined. Quite unusually for a double concerto work the solo parts, almost without exception, play together – either at the octave, in close harmony or echoing each other’s thematic material. I do not recall hearing any passages when one soloist is in anything but euphonious close conjunction with the other. Likewise the orchestral material supports rather than opposes the solo material. It makes for a very attractive work but one that consciously, it would seem, does not contain as much inherent drama as many Sawyers scores which is perhaps where the sense of neo-classicism comes in.

The following work is the Remembrance for Strings which is firmly in the tradition of elegiac British works for string orchestra. Its genesis was a commission from a friend to write a work marking the loss of the friend’s mother. Apparently she enjoyed Sawyers’ orchestral tone poem Valley of Vision hence Sawyers has included veiled references to that work. Also, the request was for a piece “akin in mood to the Elgar Elegy for Strings”. Running to 8:50 I would say this wholly successfully fulfils the commission. This is an immediately attractive and indeed impressive work with the string writing grateful and effective. Of course there are echoes of other similar meditative string works but that is a function of the medium and style rather than being any lack of originality. Here Sawyers favours melodic material that is primarily created out of step-wise progressions. This allows the music to expressively unfurl up to a series of impassioned but well judged climaxes. The string group listed for the English Symphony orchestra is relatively small – 8.6.4.4.2 – but the sympathetic recording environment of the Wyastone Concert Hall ensures a rich and full sound throughout. Woods’ pacing of the score feels unforced and effective. All in all a genuinely attractive and ‘practical’ addition to the string orchestra repertoire.

Much the same can be said of the following Concerto for Viola and Orchestra. This work also follows the traditional three movement fast/slow/fast format although on a slightly smaller scale – roughly 22 minutes to the double concerto’s 25. Daniel Rowland swaps his violin for the viola with extremely impressive results. The concept of the viola as the “Cinderella” instrument is long gone now with a raft of impressive new works played by equally impressive young soloists giving the lie to such a notion. In this work the interaction between soloist and orchestra is still quite playful but perhaps somewhat more traditional in the sense of occasional ‘opposition’ between solo and orchestral group. Again the engineering is just about ideal placing the soloist forward of the orchestra although not in an inflated sense but at the same time allowing the meticulous detail of Sawyers’ scoring to be rewardingly audible. Here the angular thematic material strives upward from the opening pages giving the music a restless yearning that is compelling – the secondary material in the woodwind is more linear again in an overall descending arc and the contrast and development of these two simple shapes makes for a strikingly effective opening movement.

The central Andante is – as in the double concerto – the longest movement of the work and again beautifully sustained. Sawyers’ use of harmony is always essentially tonal even if often ambiguously so. This ambiguity gives his music this sense of unsettled questing so even when the tempo and harmony is relatively static the music draws the listener gratifyingly forward. And then when a final resolution is found as in the last bars of the movement the sense of arrival is very powerful. Sawyers describes the closing Allegro Moderato as a “lively rondo-type movement with some expressive moments”. Again the melodic material strives upwards but in phrases that alternate between the angular and the lyrical. But the angularity here is playful and provides an effective contrast to the moods that prevailed earlier in the work. Again Rowland’s virtuosity is very impressive and makes light work of the demanding solo part. As in the double concerto Sawyers seems to be exploring a more explicitly lyric-melodic style with the sense of a neo-classical finale present in this work too. The fairly abrupt ending to the work is a slight surprise although it is well-played by the English Symphony Orchestra.

The Octet was a 2007 commission from a chamber group for a concert that would also feature Schubert’s Octet hence the instrumentation of string quartet plus bass, clarinet, horn and bassoon. The work is written in a single span lasting here 15:04. Interestingly where the Schubert undoubtedly sounds like a large chamber work, Sawyers’ sound like a small-orchestral one. I cannot quite put my finger on why this should be – whether it is the handling of the instruments individually or collectively or the fullness of the recording which certainly suggests more than just the eight players. Although continuous there are clearly distinct sections to the work from the energetic opening to the richly lyrical central Andante to the closing muscular agitato. This gives all the players opportunities for warmly expressive solos – the liner list all the players in the orchestra and the Octet so particular credit to Emily Davies’ beautiful violin solos as well as Alison Lambert on clarinet. But to be fair the entire group plays with great skill.

Hearing this 2007 work alongside the more recent concerti does seem to underline the idea that Sawyers’ music is moving from a more dissonant knotty place to somewhere of greater clarity and expressive simplicity. I have to say I enjoy hearing this sense of compositional evolution. Certainly collectors who have enjoyed this series of discs will find the continuing journey rewarding and compelling. The list of works on Sawyers’ website shows a further two, as yet unrecorded, symphonies so the hope and expectation must be for further discs of similar stature.

Nick Barnard

Help us financially by purchasing from