Nathan Milstein (violin)

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Violin Concerto in D major, Op 61 (1806)

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897)

Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 77 (1878)

Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847)

Violin Concerto in E Minor, Op.64 (1844)

Pyotr Ilych Tchaikovsky (1840-1893)

Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 35 (1878)

Max Bruch (1838-1920)

Violin Concerto No.1 in G Minor, Op. 26 (1868)

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra/William Steinberg (Beethoven, Tchaikovsky)

Philharmonia Orchestra/Anatole Fistoulari (Brahms); Leon Barzin (Mendelssohn and Bruch)

rec. January 1955 (Beethoven), April 1959 (Tchaikovsky), October 1959 (Mendelssohn and Bruch), June 1960 (Brahms)

Urania WS121.408 [75 + 79]

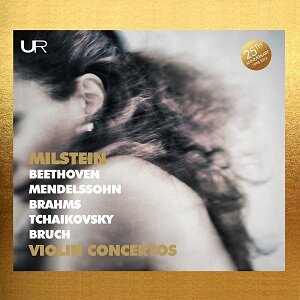

In blurred outline, long hair falling over her naked back, a woman is seen in fugitive motion. Her hair is thick, sculpted around her ear, and seems to be buffeted by a gently unexpected zephyr. Yes, it’s cover artwork, courtesy of Gianmario Masala, photographer and ‘visual artist’ (no less). ‘Milstein’ it says on the album cover and word associating as I was, I immediately assumed it was Maria Milstein, who has recently recorded Prokofiev’s Violin Concertos and might soon be expected to record the quintet of concertos outlined on the front cover. However, no, the female cover art is deceptive and the small photograph of Nathan Milstein on the back tells us what we should have been told on the cover. Incidentally, for connoisseurs of violin-focused erotica I can recommend the initial release of this material by Urania in June 2016. Discretion dictates that I leave you to discover it.

Urania is celebrating its 25th birthday, as it notes, and with it comes this gatefold release with the bare minimum of track details such as recording dates, but no original catalogue numbers or reissue numbers and certainly nothing as vulgar as liner notes. European copyright laws being what they are, I assume that sufficient time has elapsed for Urania to release this material – the recordings date from 1955-60, the locations London and Pittsburgh. The majority of Milstein’s commercial concerto recordings were made either with the Philharmonia in London, with conductors Anatole Fistoulari and Leon Barzin, or the Pittsburgh Symphony and William Steinberg.

Milstein is the trickiest violinist for reviewers to write about. Lacking idiosyncrasies – but possessing infinite varieties of subtlety – the concertos go ‘as they should’ and one can listen undistracted by false gestures. In that sense, only Grumiaux approached Milstein. The Beethoven (Pittsburgh, Steinberg, 1955) is magisterial in its accomplishment with unimpeachable tempi and expressive contours always within the bounds of fine connoisseur taste. Trills are exceptionally tight, and Milstein’s own cadenzas extremely fine; why don’t more players use them? Clarity of articulation is a given.

Milstein had something of a reputation for not getting on with conductors but from the sound of it, at least, he got on with Steinberg. If one misses a more emotive commitment, especially in the slow movement, the sheer aristocracy of Milstein’s command should be compensation. The Brahms (Philharmonia, Fistoulari, 1960) is commanding and pristine and was always one of his most centrally recommendable recordings, with the orchestra on top form under a rather taken-for-granted conductor. Milstein’s cadenza is dispatched with technical aplomb and brilliance and his awareness of portamenti is best illustrated in the slow movement. He is exciting and communicative in the finale.

The Mendelssohn-Bruch LP brace with which I grew up was Milstein’s Pittsburgh recording: here, however, we get the Philharmonia-Barzin brace, hardly less good. His Mendelssohn is crystalline and lithe, scintillatingly played but without any sense of vulgarity: pristine but not romantic. The Bruch possesses a familiar stylistic refinement and subtlety that motors the music rather than tonal heft – not the ideal, perhaps, in romantic generosity but always calibrated with precision. If his most volatile and engaging recording of the Tchaikovsky was the recording with Frederick Stock in Chicago, the Pittsburgh-Steinberg collaboration offers a similar instrumental finesse in, obviously, stereo sound.

These well-transferred concerto recordings feature well-tilled ground and will only be of interest to newcomers to Milstein’s art. You won’t find out more because, as I noted, there is no booklet. Surely, though, it’s high time for a comprehensive Milstein box?

Jonathan Woolf

Help us financially by purchasing from