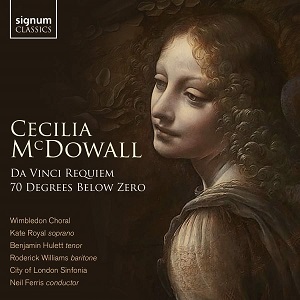

Cecilia McDowall (b. 1951)

Da Vinci Requiem (2019)

70 Degrees Below Zero (2012)

Kate Royal (soprano); Benjamin Hulett (tenor); Roderick Williams (baritone)

Wimbledon Choral

City of London Sinfonia/Neil Ferris

rec. 2022, St Augustine’s Church, Kilburn, London

Texts & English translations included

Signum Classics SIGCD749 [57]

This CD contains recorded premieres of two important works by Cecilia McDowall, both of which were commissioned to mark significant centenaries.

Though Wimbledon Choral can trace its origins back to 1870, the choir was reformed during the First World War. To mark 100 years since it was re-founded it commissioned a new work from Cecilia McDowall. Da Vinci Requiem, which was the result, was an ingenious idea on the composer’s part. She explains in her booklet notes that in 1946 her mother gave her father, as a wedding gift, a copy of the recent English translation of The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci. She goes on to tell us that “[a]s a child, I loved poring over these large dusty tomes of Leonardo’s, filled with the most extraordinary sketches”. She hit on the idea of combining the text of the Latin Mass for the Dead with extracts from Leonardo’s writings. By a neat symmetry, this gave her the opportunity to mark not only Wimbledon Choral’s centenary but also the 500th anniversary of the death of Da Vinci (1452-1519).

Da Vinci Requiem, which plays for some 34 minutes, is cast in seven movements and the composer describes its structure as that of an arch. The chorus chiefly sings Latin words from the Mass from the Dead; the two soloists, soprano and baritone, are allotted da Vinci’s words (in English) and, occasionally, portions of the Requiem text.

The music of the opening movement, ‘Introit and Kyrie’, is dark and restless. Da Vinci’s words are sung by the soloists in the foreground while the Latin text is entrusted to the choir, sometimes to accompany the soloists and sometimes as the centre of attention. The composer says that the music is sometimes dissonant, and so it is, yet even when dissonant it remains melodious and approachable: the communication with the listener is direct, both here and in the rest of the work. The second movement, for soprano and orchestra, departs from McDowall’s overall scheme in that the English text is not by Da Vinci but inspired by him. The soloist sings lines by Dante Gabriel Rossetti from For ‘Our Lady of the Rocks’ by Leonardo da Vinci. Rossetti wrote the poem in 1848 while seated in front of Da Vinci’s picture of that name in the National Gallery in London. As the composer points out, the picture was painted for a church in Milan in 1485 while the city was in the grip of bubonic plague. Given those associations, it’s unsurprising that McDowall set the words to dark, dramatic music. The orchestral scoring is dark-hued and the vocal line is impassioned and beseeching in nature. Kate Royal rises to the challenge in a committed performance.

Next comes ‘I obey thee, O Lord (Lacrimosa)’. This is for choir and orchestra. Given that the Latin element of the text is the concluding portion of the ‘Dies irae’, the music is surprisingly lyrical, though I hasten to add that it works very well. and though the music may be lyrical it is in no way lacking in intensity. The Fourth movement – the apex of McDowall’s compositional arch – is ‘Sanctus and Benedictus’. Here again the soloists are absent, as are any words by Da Vinci. The setting is strongly rhythmical, lively and celebratory. It’s a most attractive movement.

Next comes ‘Agnus Dei’ which reverts to the scheme of combining words from the Mass for the Dead and by Da Vinci. The choir’s music is overtly based on plainchant. The writing for both choir and orchestra is sombre and above the ensemble soars a fervent solo soprano line. After this, the baritone takes centre stage in ‘O you who are asleep’. Da Vinci uses sleep as a metaphor for death – early on, the soloist sings the words ‘Sleep resembles death’. The orchestration is most imaginatively coloured and the melodic line is eloquently delivered by Roderick Williams. Finally, as we reach the other side of Cecilia McDowall’s arch, she sets ‘Lux aeterna’, involving all the performers. She focuses on the concept of Light Eternal, which allows us to view death positively, and selects words by Da Vinci that reinforce that idea. The music is confident and hopeful in tone. Then, at the end, it reaches ever higher and, in essence, fades out of our hearing (and sight).

I have been very impressed by Da Vinci Requiem. The concept of combining Leonardo’s writings with the words of the Mass for the Dead is original and intriguing – and very successful. I’ve admired Cecilia McDowall’s music for a long time, so expectations were high – and have been fulfilled. Her settings of the texts in these seven movements are as eloquent as they are sincere; as ever, this composer responds acutely to the words she chooses to set. The solo parts are full of interest and I would imagine that the choral writing is very rewarding to sing. The orchestration is consistently inventive. The performance, led incisively by Neil Ferris, is excellent: it seems clear that Wimbledon Choral were determined to show their commission in the best possible light and they did so with excellent, disciplined and highly committed singing. In the note about the choir in the booklet we read that their centenary was an opportunity for the choir not just to look back but to express their collective optimism for the future. “That is why we decided to commission a major new work, our own piece of choral history, part of the wonderfully vibrant modern British choral tradition”. I think that providing the stimulus for a significant addition to the repertoire is in itself really laudable. But the choir has gone a step further. By bringing about this splendid recording of the new work – and I bet they had to work hard to raise the funding – they have contributed further, by bringing Da Vinci Requiem to the attention of a wider public than would have been the case if they’d simply performed it once in concert. One hopes this recording will encourage further performances of this important new work. As a member of a choir myself I can only offer congratulations to Wimbledon Choral on their enterprise.

The disc is completed by what I’m sure must be another recorded premiere in the shape of McDowall’s 70 Degrees Below Zero. The piece, for tenor solo and orchestra, was commissioned jointly by the Scott Polar Research Institute and the City of London Sinfonia to mark the centenary, in 2012, of Captain Scott’s ill-fated expedition to the South Pole. It was premiered by the City of London Sinfonia under Stephen Layton’s baton in Symphony Hall, Birmingham on 3 February 2012 and I heard it a few days later when they brought the programme to Cheltenham (review). I haven’t heard the piece since then so I was very glad to have the opportunity to listen to it again, and at greater leisure.

The piece, which here plays for some 23 minutes, is cast in three movements. McDowall wove together two elements in the text. In part she used Captain Scott’s own words in the outer movements. A lot of the first movement and all of the second consists of settings of poems specially composed for her in 2011 by Seán Street. In passing, it should be noted that 70 Degrees Below Zero isn’t the only occasion on which McDowall and Street have collaborated: he also supplied some poetry for her very moving piece about the heroic nurse, Edith Cavell, Standing as I do before God (2013).

The first movement, ‘We measure’ features urgent but lyrical writing for the tenor soloist and eventful writing for the orchestra. I mean no disrespect, but I think that movement is just the prelude and we begin to get to the heart of the matter in the middle movement ‘The Ice Tree’. If I interpret Street’s poetry correctly, I think he’s conveying imagery of the paper on which Captain Scott would document his last expedition. The orchestral writing – strings and woodwind – has a glacial chill to it and the tenor’s line, plangently sung by Benjamin Hulett, is full of tension. McDowall’s music is accessible, but even so this movement is far from an easy listen.

The final movement. ‘To my widow’ sets to music the last letter which Captain Scott wrote to his wife at a time when he knew the end was near; it was later found on his body. Looking back to my review of the 2012 concert, I see I said of this movement: “The words reveal the sadness of Scott, who knew by then that he would never again see his wife and baby son, and they also show his courageous dignity. I thought that McDowall’s music conveyed the sadness very well but the emotion in her writing is pretty raw and, for me, she failed to convey the stoic dignity.” Having now listened to the piece again, I withdraw the last part of that comment. I think Cecilia McDowall does indeed convey the dignity of Scott as well as his anguish. The setting is very moving, especially right at the end.

70 Degrees Below Zero is an impressive work and I’m delighted that it has achieved a recording. Neil Ferris draws excellent playing from the City of London Sinfonia while Benjamin Hulett is simply outstanding. The clarity of tone and diction he brings to this music is admirable, and so is his emotional engagement with the piece.

This is a fine disc, showing, as so many previous recordings have done, that Cecilia McDowall is a first-rate composer who communicates splendidly with audiences. The performances have been recorded in excellent sound by engineer Mike Hatch and the documentation is comprehensive.

John Quinn

Help us financially by purchasing from