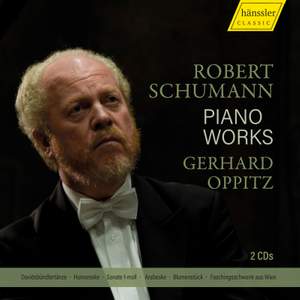

Robert Schumann (1810-1856)

Piano Works

Davidsbündlertänze, Op 6 (1837, edition 1851)

Humoreske, Op 20 (1839)

Grande Sonate in F minor, Op 14 (1836, rev. 1853)

Arabeske, Op 18 (1839)

Blumenstück, Op 19 (1839)

Faschingsschwank aus Wien, Op 26 (1839)

Gerhard Oppitz (piano)

rec. 2019, Irenensaal Baierbrunn, Germany

Hänssler Classic HC22045 [2 CDs: 142]

This new release from renowned pianist Gerhard Oppitz consists of six piano works by Robert Schumann. The Bavarian Oppitz is now seventy and has, in his long career, recorded for a number of labels. In 2009, Hänssler Classic released Oppitz’s survey of the complete Beethoven piano sonatas as both single volumes and a nine CD box set, then in 2017 his complete Schubert piano works on a 12 CD box set, which had previously been issued as single volumes.

In the 1990s, I was in a phase of exploring the music of Schumann. Later, I visited the Schumann House in Leipzig where Robert and wife Clara, née Wieck, lived early in their marriage. I learned how Schumann’s passionate emotional connection to German literature would lead him to regularly express his inner feelings using the duality of the imaginary characters he named Florestan and Eusebius to represent separate and opposing sides of his personality. Florestan is satirical, impulsive and instinctive, whereas Eusebius is sensitive, introspective and thoughtful. There was also a third character, Master Raro, whom I see as melding the technical and expressive components of the music into a single entity. Undoubtedly Florestan and Eusebius are present in his piano cycles Carnaval and Davidsbündlertänze. Schumann would also use ciphers in his music to express private thoughts such as in Carnaval, a twenty-one-piece cycle.

Schumann composed a significant number of piano works which I found were more challenging to listen to than his symphonies, concertos, chamber works and Lieder. Much has been written about Schumann’s lifelong mental health difficulties and in 2010 international concert pianist John Lill described to me in interview how ‘the music of the Schumann does show some signs of his unbalanced mental state – but Schumann was so great that his music only benefits from it, by the irregularity of it.’

Oppitz opens this Schumann collection with Davidsbündlertänze (Dances of the League of David), Op 6. Begun in 1837, the Davidsbündlertänze is a piano cycle comprising of two books, each containing nine piano pieces. Like many of Schumann’s piano works, the cycle has become a repertoire staple. Schumann named the cycle after his music society or league Davidsbündler which was part reality and part fantasy. Inspired by his love for Clara, his opening theme for the Davidsbündlertänze is based on one of her mazurkas. These are a collection of character pieces and not authentic dances. An 1838 edition of Davidsbündlertänze assigned each of the eighteen pieces to either one or both of Schumann’s Florestan and Eusebius. Schumann wrote the original version of Davidsbündlertänze in 1840 prior to his marriage to Clara and here Oppitz is using the 1851 second edition of the score. Oppitz plays these love messages to Clara splendidly and with the utmost sincerity.

Schumann wrote his Humoreske in B-flat major, Op 20 in 1839 during an enforced absence from Clara, who was visiting Paris. It was originally titled Grand Humoreske. Evidently Schumann was inspired by the German Romantic writer Jean Paul. Oppitz takes his time through the sequence of seven sections, maintaining a persuasive level of focused concentration throughout the shifting emotional personality of the score. Oppitz takes longer to play the Humoreske than twenty or so other recordings, yet time never seem to drag.

The Piano Sonata No 3 in F minor, Op 14 was originally written as a five-movement work with two Scherzi. Haslinger the publisher persuaded Schumann to omit both Scherzi to appear not as a sonata but a Concert sans Orchestre. In 1853 Schumann modified the score including restoring a Scherzo marked Molto comodo and altering the number of variations in the third movement. It is the four-movement version of the Piano Sonata No 3 titled Troisieme grande Sonate that Oppitz plays here. He excels in the tricky Finale with the unusual marking of Prestissimo possible, sustaining a substantial forward momentum of real vitality.

Schumann wrote his single movement Arabeske, Op 18 using a Rondo form during a flurry of activity in 1839. This was an emotional time for Schumann as Clara’s father wanted her to concentrate on her career as a contest pianist, fiercely objecting to Schumann seeing his daughter. Oppitz flourishes in the passages of sadness and yearning interspersed with vigorous sections.

Another work from 1839 is Blumenstück (Flower Piece), Op 19, written during Schumann’s separation from Clara when they had to rely on writing love letters. As the title suggests, this sequence of thematically intertwined sections can be visualised as flower pictures. Taking a measured approach, Oppitz reveals Blumenstückto be a charming and generally cheerful work which is often overlooked, and which Schumann actually disparaged.

The final work on the set is Faschingsschwank aus Wien (Carnival Scenes from Vienna), Op 2, the fourth work that Oppitz has chosen from 1839. Described by Schumann as a ‘romantic spectacle’ in this five-movement score Schumann is depicting Vienna in unrestrained carnival mood. Resolute and extrovert, Oppitz has full measure of the opening Allegro which is the most substantial by far and probably the most challenging movement to play. It includes a very brief quotation from La Marseillaise, at that time banned in Vienna. In the fourth movement, an Intermezzo, Mit Größter Energie (With the greatest energy), the soloist creates a brilliant near spellbinding stream of notes with an explosion of colour. Oppitz’s playing of the Finale, marked Höchst Lebhaft (Highly vivid), brims over with vitality and an unalloyed sense of merriment.

Oppitz recorded the album on a Steinway at the Irenensaal Baierbrunn. The sound has a pleasing clarity and there is a splendidly written essay in the booklet by German musicologist Wolfgang Rathert.

Gerhard Oppitz excels in these Schumann works, that he will have lived with all his career. This valuable double set provides a real opportunity of hearing a master at work.

Michael Cookson

Help us financially by purchasing from