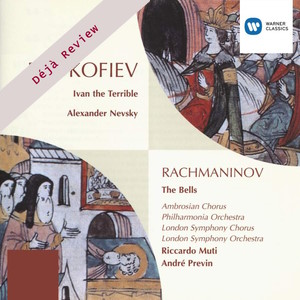

Déjà Review: this review was first published in August 2000 and the recording is still available. Ian Lace passed away in 2021.

Sergei Prokofiev (1891-1953)

Ivan the Terrible

Alexander Nevsky

Sergei Rachmaninov (1873-1943)

The Bells

Irina Arkhipova (mezzo-soprano); Anatoly Mokrenko (baritone); Boris Morgunov (narrator)

Ambrosian Chorus (Ivan)

Sheila Armstrong (soprano); Robert Tear (tenor); John Shirley-Quirk (baritone) (Bells)

Anna Reynolds (mezzo-soprano) (Nevsky)

Philharmonia Orchestra/Ricardo Muti (Ivan)

London Symphony Orchestra and Chorus/André Previn (Nevsky, Bells)

Originally reviewed as EMI Double Forte 5733532

Warner Classics 2435733535 [2 CDs: 152]

This is a very clever idea to package Prokofiev’s two major film scores together in this budget presentation and I urge all adventurous lovers of film music who are unfamiliar with this music to invest in this 2CD album. However I would add one caveat. Budget prices often mean sacrifices; and the sweeping marketing policy of EMI to pare down the notes for their mid-price/budget albums is a grave mistake as far as this reissue is concerned for no librettos are given. This might not be so serious with Alexander Nevsky but it is a grave omission as far as Ivan the Terrible is concerned, which occupies the whole of CD1 in this set, because there is a considerable narrative spoken in Russian. Clearly without a translation one is listening very much blind and this film is rarely screened or transmitted. Given some of the 26 numbers/movements have reasonably descriptive titles like: ‘The Gunners’ or ‘The Storming of Kazan’ but what are we to make of others like ‘The Swan’, and ‘Ocean’?

Lest I deter prospective purchasers, I hasten to add that this music can be very much enjoyed for its own sake (see review that follows).

Sergei Eisenstein’s classic film of Alexander Nevsky dates from 1938 and, incredibly, Prokofiev composed the music at breakneck speed in a matter of days (presumably the very complex orchestrations took longer?). The story is based on the Russian defence of Novgorod in 1242, in which the invading Knights of the Teutonic Order were held at bay most spectacularly during a battle on the frozen waters of Lake Chud.

In 1939 Prokofiev reassembled his Alexander Nevsky music in the form of a ‘cantata’ expressly for concert performance. As such it has proved extremely popular and is often performed. It is this cantata which is presented here. This 1971 André Previn recording made in the splendid acoustic of London’s Kingsway Hall is magnificent and stunningly thrilling.

The opening movement is entitled ‘Russia under the Mongolian Yolk’ and it is a vivid example of Prokofiev’s very individual style. The mood is suitably mournful and oppressive, and an extraordinary combination of (I think) bass clarinet and tuba produces a forbidding tone that seems to speak at the same time of those that crush and the crushed.

The following ‘Song of Alexander Nevsky’ begins with despairing voices until the tempo picks up and the mood turns to one of defiance. The next movement is another vivid evocation – ‘The Crusaders in Pskov’. You can visualise the heavily armoured Teutonic Knights with their dauntingly huge helmets. The crushing music, with heavy drums and cymbal crashes, speaks of their cruelty and barbarism. In response, the voices of the people turn from submission to revolt but the movement ends with a welcome moment of tenderness from the violins. ‘Arise, Ye Russian People’ is a fine noble tune with voices supported by colourful orchestrations that include bells and xylophone.

But the most significant movement, and the most memorable, is the celebrated 14-minute ‘The Battle on the Ice.’ It begins with a wintry scene: the chill is palpable with icy trumpets and shivering cellos. Swirling strings invite you to picture frosty beards of mist swirling over the surface of the Lake. Then you hear the Knights approaching from a distance. First, at a slow canter. Listen their pace quickens, now they are charging. Prokofiev sounds the chink of spurs, the clatter of armour – and the creaking, snapping breaking of ice as the Knights are confounded. This whole episode is a marvellous crescendo utterly thrilling with the voices adding power and dramatic tension. Combat, chaos, victory and exultation!

The mood of the final minutes of the movement is echoed in the subsequent movement, ‘The Field of the Dead’. First we hear a beautiful limpid melody with liquid strings gently eddying, ebbing and flowing; its as if we have been transported to the Elysian Fields. Then comes a poignant elegy with an affecting solo sung by mezzo-soprano Anna Reynolds. The cantata ends with the resounding celebratory ‘Alexander’s Entry into Pskov’ to the sound of many bells.

Following the success of Alexander Nevsky, Eisenstein was keen to employ Prokofiev on his 1942 blockbuster epic, Ivan the Terrible. The film was based on the life of Tsar Ivan IV of Russia whose reign (1547-84) was marked by a great progress in terms of political reform – but at a price. Those who dissented were dealt with severely, as in 1570 when he had thousands of people slaughtered in Novgorod (on very flimsy evidence) believing they were not among his keenest supporters. The film was made in two parts; part two began shooting in 1946. Part One had been awarded a Stalin Prize but the follow-up was denied a public showing on Stalin’s express orders. It is believed Stalin strongly identified himself with Ivan, and had no desire to be reminded of the atrocities that characterised the latter half of his reign. And so Ivan the Terrible did not receive a complete screening until 1958, five years after Stalin’s and Prokofiev’s deaths, and ten after Eisenstein’s.

Concert-goers had to wait for their first taste of this huge score until Alexander Stasevich reassembled Prokofiev’s incidental music in the form of an ‘oratorio’ in 1961.

Ricardo Muti’s recording is — to use that overworked phrase — absolutely stunning, it reaches out at you and grasps you and holds you from first to last (narration frustrations, see above, notwithstanding). The work is divided into 26 sections, most averaging 2½ minutes but with a central section of two major dramatic episodes: The Storming of Kazan (9:47); and ‘Ivan’s Appeal to the Boyars’ (8:06). These two numbers (as do others) display a keen sense of the theatrical. The shorter preceding cue ‘The Gunners’, is noble and patriotic and forceful with brisk staccato combative material against tolling bells but there is also typical Slav melancholy and nostalgia. ‘The Storming of Kazan’ opens with trudging tuba figures, snare drumings and bass drum booms as though a heavy canon was being trundled into position. Then trombones snarl before the voices of the besieged(?) people are heard in hymn-like tones, the music, for a while, turning pastoral/mystical. But soon battle commences with raging trumpets, bass drum thuds crashing gongs and cymbals and the music becomes increasingly frantic – tremendously exciting stuff! ‘Ivan’s Appeal’ that follows mixes tension with tenderness. Impassioned strings mix with consolatory choruses.

Another spectacular number is ‘I will be Tsar!’ with huge cymbal crashes and choruses of big bells. This huge, theatrical set piece rivals the Coronation Scene from Mussorgsky’s Coronation Scene from Boris Gudunov! ‘March of the Young Ivan’ is another spectacular but here the choral and orchestral music after a heroic quick march, takes a decidedly unpleasant turn, all snide, wheedling and barbaric, revealing the less attractive side of Ivan’s character. This is just another example of Prokofiev’s skill in vivid portrait painting using just a splash of quirky colouring. Calmer material (but working up to a thunderous climax) comes in the number entitled ‘Ocean’ with Irina Arkhipova and choir intoning above impressionistic orchestral tissues. ‘Celebration Song’ is more restrained than its title might suggest, this is one of the warmest and most compassionate numbers in the work.

Rachmaninov’s Choral Symphony, The Bells, could equally have been recommended listening when the composer was featured recently in ‘If Only They Had Scored For Films’, on Film Music on the Web, for this work is another powerful and vivid set of evocations.

Rachmaninov himself, in describing this work, remarked how the sound of bells dominated life in Russia. He had settled with his family in flat in the Piazza di Spagna in Rome in 1913 where he composed The Bells (and his 2nd Piano Sonata). The Bells, based on the verses by Edgar Allan Poe, is scored for soprano, tenor and baritone soloists, chorus and large orchestra, and it evokes the life-cycle of birth, marriage, terror and death. These in turn are related to different sorts of bells: silver, golden, brass and iron.

The opening movement, ‘The Silver Sleigh Bells’ celebrates youth, joy and romance with choir and tenor Robert Tear singing of a scenario with lovers dreaming under the stars. The following ‘Mellow Wedding Bells’ has soprano Sheila Armstrong and the choir singing tenderly of love consummated. But the music also has a mournful edge as though Rachmaninov, rather than Poe, was warning us of the responsibilities and ties of marriage and that it is the first step on the downward path to death and oblivion. Clamour, terror and despair characterise the break-neck Presto ‘The Loud Alarum Bells’. In Previn’s hands this movement has irresistible drive and pungency. The bleak monotonous declamations of the final movement ‘The Mournful Iron Bells’ that features that fine baritone John Shirley Quirk, is evidence again of Rachmaninov’s fatal spirit. (Seated at Tchaikovsky’s desk, perhaps he was very conscious of the latter’s Pathetique Symphony?)

This is another classic Previn performance with soloists, choirs and the LSO in excellent form.

Once more, inclusion of the words of the work would have helped.

Ian Lace

Help us financially by purchasing from