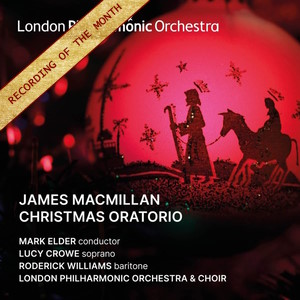

Sir James MacMillan (b 1959)

Christmas Oratorio (2019)

Lucy Crowe (soprano)

Roderick Williams (baritone)

London Philharmonic Orchestra & Choir / Sir Mark Elder

rec. live, 4 December 2021, Royal Festival Hall, London

Texts & English translations included

LONDON PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA LPO-0125 [2 CDs: 94]

This pair of CDs preserves the London premiere of Sir James MacMillan’s Christmas Oratorio. It may seem odd to review a Christmas piece in February; unfortunately, the discs only reached me at the end of January. However, I felt somewhat reassured when I read in the booklet that the world premiere of the piece, under the composer’s baton, took place in Amsterdam in the month of January in 2021. Actually, that wasn’t intended to be the premiere: the LPO was one of the co-commissioning orchestras and I understand that they were scheduled to give the world premiere in December 2020 but that performance fell victim to Covid restrictions; even the Amsterdam performance in January 2021 had to be given without the presence of an audience. Happily, by the time of the present performance it was possible to perform the oratorio to an audience, though their presence couldn’t be detected as I listened and there’s no applause at the end.

The Christmas Oratorio is scored for two soloists, an SATB choir and what the composer describes as an orchestra of “modest size”, namely double woodwind, brass, percussion, harp, celeste and strings. The work has a clearly defined structure: it is divided into two parts, of roughly similar length, and each part consists of seven movements. Both parts begin and end with an orchestral Sinfonia. That first Sinfonia is followed by a movement for chorus and orchestra; then comes an aria for one of the soloists with orchestra. At the centre of each Part there is a Tableau, in which all the forces are involved, followed by an Aria for the other soloist, a movement for Chorus and Orchestra, and, lastly, the second Sinfonia. In structural terms, therefore, the work is palindromic.

In each of the work’s two Parts the central Tableau is the key section and it’s interesting to note what MacMillan does in each of these. The Tableau in Part One relates the nativity story as related in Chapter 2 of St Matthew’s Gospel. However, the narrative begins not with the birth of Christ but with the visit of the Magi – the shepherds are notable by their absence. MacMillan focuses on Herod’s attempt to get to the infant Jesus by tricking the Magi, the adoration of the Magi, and the subsequent flight of the Holy Family into Egypt whereby they escape the massacre of the Holy Innocents. The Tableau in Part Two is not narrative but, rather, contemplative. Here, MacMillan sets the first eighteen verses of St John’s Gospel (‘In the beginning was the Word’).

Part One of the Christmas Oratorio opens with an orchestral Sinfonia. Here, woodwind and the twinkling sound of the celeste are to the fore and much of the music has a nimble dance-like character. There follows a movement for chorus and orchestra in which MacMillan sets, in Latin, the Magnificat antiphon for 21 December, ‘O Oriens’; here, the choral writing is rooted in tradition, with some beautiful harmonies. This is followed by a section of the Creed in which the hushed a cappella ‘et incarnatus est’ is especially memorable. The section closes with words from the ‘Alma Redemptoris Mater’ where MacMillan’s writing for both chorus and orchestra constitutes an exuberant outburst of praise for the mother of Christ.

The first Aria in the work is a setting for soprano and orchestra of Robert Southwell’s poem which begins ‘Behold a silly tender babe’. This is a very fine piece of writing and Lucy Crowe’s delivery is expressive and involving. She makes a lovely sound, though even when following the words in the booklet I didn’t aways find her diction ideally clear. The Tableau that follows shows MacMillan’s gift for dramatic writing, not just for voices but also for the orchestra. He uses the choir to deliver the narration and the way the music is laid out ensures that the words can be very clearly heard – so, too, does the excellent diction of the London Philharmonic Choir. There are also some telling interjections by the two soloists. The depiction of the massacre of the Innocents is particularly graphic: MacMillan repeats over and over again a strident orchestral chord, preceded each time by a loud bass drum stroke. Clearly, this represents the slaying of a child, and the number of times the device is repeated reminds us just how many babies were murdered on Herod’s orders. After this searing drama we hear an Aria for the baritone soloist. The text is a poem by John Donne. The vocal writing is intensely lyrical while the orchestral accompaniment is keenly imagined. Roderick Williams sings his solo with great feeling and, as ever with this artist, terrific understanding and communication of the words. There follows a setting for chorus and orchestra of ‘Hodie Christus natus est’. This is jubilant music, full of drive and exaltation. That exaltation is experienced even in the passages where the dynamic level is lowered. The orchestra concludes Part One with another Sinfonia. The music is fast and strongly rhythmical; the music conjured up for me the spirit of the final movement of Janáček’s Glagolitic Mass. Sir Mark Elder and the LPO impart terrific energy to the music.

Part Two opens with another orchestral Sinfonia in which the music is fast and dramatic. Then the choir sings (with orchestral support) the Christmas Day Matins responsory, ‘O magnum mysterium’. I think this may be the most technically challenging music so far for the chorus. The choral writing is quiet but with complex textures, all of which conveys gentle ecstasy. Meanwhile, the highly imaginative orchestral writing provides a backdrop that is at once subtle but also highly decorative. The baritone Aria which follows maintains the ecstatic mood. The words are taken from Milton’s ‘On the morning of Christ’s Nativity’, which MacMillan sets to rapturous music. The vocal line contains many ecstatic melismas while the orchestral contribution, richly imagined, is restrained for the most part but telling nonetheless.

As I’ve said, the central Tableau sets, for the full forces, the opening of St John’s Gospel. MacMillan responds to the majestic poetry of the text with memorable music which consistently conveys a sense of wonder. In the middle of the movement the two soloists take over the text from the chorus. Their duet is sparely accompanied, allowing us to focus on the words themselves. Then the chorus returns for the passage which begins with the key words ‘And the Word became flesh’. From here to the end of the movement, the writing is particularly beautiful and impressive: MacMillan engenders subdued, rapt contemplation of the mystery of the Incarnation. This is a marvellous movement and, for me, the key section of this work. The last of the four Arias is allotted to the soprano soloist; as in Part One, she has lines by Robert Southwell to sing (‘As I in hoary winter’s night stood shivering in the snow’). MacMillan makes this into a big, dramatic piece, suitable for the poet’s vision that ‘A pretty babe all burning bright did in the air appear’. Lucy Crowe rises to the challenge of this aria with powerful, expressive singing; the music offers many opportunities to display the gleaming top register of her voice. The orchestral accompaniment is busy and highly effective.

From this point on, MacMillan is done with drama. The final chorus is a setting of ‘The Christ Child’s Lullaby’, an English version by Fr Ranald Rankin (1811-1863) of Scottish Gaelic words. Here, the choir is joined by the celeste in quiet, radiant music; MacMillan has used a traditional Scots melody. The setting is very lovely and also touching in its simplicity. The last word is given to the orchestra. The concluding Sinfonia continues the tranquil vein and much of the movement is played just by a small group of solo strings in which the orchestra’s leader, Pieter Schoeman has a beguilingly prominent role. The mood of the music is warm and reflective and eventually it swells to an affirmative but not overblown ending.

James MacMillan’s Christmas Oratorio is a very important work. He has taken words which clearly matter deeply to him and has set them to accessible yet profound music, all of which constitutes an eloquent and very satisfying whole. If there is any justice in this world, the work will be widely heard for I’m sure it will exert a strong appeal to audiences. MacMillan has helped the work’s cause by the pragmatic way in which he has written the score. Two vocal soloists of the first rank are required but, on the other hand, I would judge, without having seen a score, that the chorus parts are well within the range of an accomplished, well-trained choir of experienced singers – as the members of the London Philharmonic Choir here prove triumphantly. The orchestra has a challenging assignment but, by compensation, the forces are not wildly extravagant. So, the way is clear for professional orchestras in the UK – and beyond – and their associated amateur choruses to take up the piece. I am confident they will find it rewarding.

The present performance is tremendous. I noted one or two tiny instances where, under studio conditions, a slight imperfection of ensemble might have been corrected. Frankly, though, I’d rather have these tiny blemishes – which don’t impede enjoyment at all – as the “price” for hearing such a committed, exciting live performance. The two soloists are superb; I admired greatly the commitment and accomplishment of the London Philharmonic Choir while the LPO itself is on splendid form, delivering MacMillan’s richly imagined colourful orchestration with panache. Sir Mark Elder was an ideal choice to conduct; he leads the performance marvellously, bringing to bear all his experience of controlling large forces and dramatic scores.

The presentation of this set is very good. The recorded sound conveys the performance very successfully. In particular, the soloists and also the chorus are balanced very well with the orchestra. In addition, producer Andrew Walton and engineer Deborah Spanton have ensured that all the detail of MacMillan’s orchestral tapestry can be clearly heard. The booklet includes the texts and translations. In addition there’s a short introduction to the work by the composer himself and also a useful note about MacMillan and this new work by Anthony Fiumara. However, in the course of my researches into the background of the Christmas Oratorio I came across an even better introductory essay. The night after the performance here recorded, the same forces repeated it in Saffron Hall, Saffron Walden. Joanna Wyld wrote an excellent programme note for that performance, which provides a fine introduction to the new work; you can access it here.

Don’t worry that Christmas is behind us for another year I urge readers to experience this terrific new score for themselves as a matter of urgency. It’s not just a Christmas work; it’s also a profound reflection on the Christmas message and one, moreover, that in Part One doesn’t flinch from the darker side of the Christmas narrative. As such, it has something to say to us at any time of the year.

John Quinn

Help us financially by purchasing from