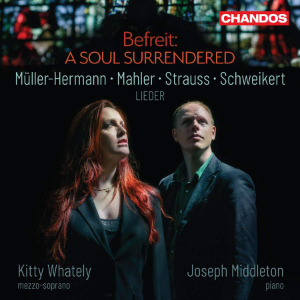

Befreit: A Soul Surrendered

Kitty Whately (mezzo-soprano)

Joseph Middleton (piano)

rec. 2022, Potton Hall, Dunwich, UK

German texts & English translations included

Chandos CHAN20177 [68]

Kitty Whately is a singer I’ve admired for quite a while. Though I first saw her in ENO’s production of Vaughan Williams’ Pilgrim’s Progress back in 2012 (review), it was her first CD, on which she was partnered, as here, by Joseph Middleton, that really caught my attention (review). Since then, I’ve heard her on recordings of songs by Jonathan Dove (review) and Vaughan Williams (review) and she’s always made a very good impression. I’m delighted to find her now turning her attention on disc to Lieder. From a note that she’s written for Chandos it appears that she and Joseph Middleton planned the programme to include items by Mahler and Strauss and those masters duly make their appearance here. However, I hope I’ll be forgiven if I focus chiefly on the other two composers represented in the programme, both of whom were completely new to me.

Since the names and music of Joanna Müller-Hermann and Margarete Schweikert may similarly be unfamiliar to some of our readers, a little biographical information seems in order and for this I draw on the excellent booklet essay by Paul Griffiths. The Austrian, Joanna Müller-Hermann was the daughter of a senior civil servant. Initially, it seems, she was unable to pursue her musical education to a high level but that changed when she got married in 1893. I infer that her husband did not hold her back – unlike the attitude Mahler took towards the compositional activities of Alma (who was a friend of Joanna) – and she was able to study with a variety of prominent figures in the Viennese musical establishment, including Zemlinsky and Franz Schmidt. Griffiths tells us that she also had “some contact” with Schoenberg. A good deal of her music was published and from 1918 onwards she occupied a teaching position at the New Vienna Conservatory. The German composer, Margarete Schweikert was born in Karlsruhe. Her father was, perhaps, less exalted than Müller-Hermann’s in that I believe he was by profession an insurance salesman, but he also had musical accomplishment and was a music critic for journals in Karlsruhe and Stuttgart. Margarete also benefitted from conservatoire education and she followed her father’s example by becoming a music critic. Griffiths tells us that in her later years she worked as an advisor for GEDOK, the leading organisation for female artists in Germany and Austria. So, here we have two female composers whose musical talents do not appear to have been repressed during their respective lifetimes. Both composed significant amounts of music, their works were published and performed, and they were able to make music their profession. Yet, how many have heard of their music today?

Joanna Müller-Hermann is represented here by five songs, all of which I enjoyed and admired. The very first one, Wie eine Vollmondnacht creates an immediately favourable impression; it’s slow and rapturous. Kitty Whately does it justice; her mezzo is full-toned and rich and there’s good clarity of both tone and diction, as is the case throughout the recital. Der letzte abend is romantic and expressive. The music is deeply-felt, as is the performance by Whately and Middleton. The group of three songs that comes later in the programme doesn’t disappoint either; all are fine pieces and Whately’s engagement with both words and music is never in doubt. I particularly liked the intensity and passion of both music and performance in In Memoriam.

Paul Griffiths observes in his booklet essay that Margarete Schweikert, born nine years after Müller-Hermann, “grew up in a different world, after the great wave of modernism had crashed over even the more conservative parts of the musical landscape. A moment with her music will show this. Gone are the plush textures and harmonies, the closeness to a milieu – Viennese, early twentieth-century – that we may feel as familiar.” Griffiths attributes this, at least in part, to the fact that Schweikert’s principal teacher, Joseph Haas, gave his pupil rather different guidance compared to the training imparted to Müller-Hermann by the likes of Zemlinsky. On the evidence of what I hear on this disc I wouldn’t challenge that summary at all. That said, these songs by Schweikert can be enjoyed as a late flowering of the German romantic tradition.

Totenhausen is a complex, through-composed song in the course of which the music responds to each change of emphasis in the poem. Here, Schweikert really tests both singer and pianist but, of course, Whately and Middleton are fully up to these challenges. Zusammen sterben is a dark-hued song; the poem, which is a translation of an anonymous Japanese text, is all about a pair of lovers wishing to die together. Unser Haus is thought to be the earliest of the composer’s songs included here. Paul Griffiths aptly describes it as “a charming winter picture, stationery but not at all monotonous. I was impressed too by Die Entschlafenen, an eloquent song about the power of death which Kitty Whately puts over very convincingly.

The songs by both of these composers are impressive and far too good to moulder way in obscurity. Chandos don’t seem to be claiming any of these as first recordings but I can’t imagine that the songs have enjoyed a wide currency. Looking back on MusicWeb, I was able to find a recording of Müller-Hermann’s 1912 Cello Sonata (review) but I couldn’t immediately locate reviews of any music by Margarete Schweikert. As I hope I’ve indicated, all the songs here recorded are fine compositions in which the respective composers identify strongly with the texts they set. Vocal lines and piano parts are full of interest. Kitty Whately and Joseph Middleton have done both composers notable service through their committed advocacy and deeply musical performances. I should like to hear more songs by both ladies – I understand that Schweikert composed over 160. The only slight cavil is that while all the songs are eloquent and deeply-felt I wonder if either composer wrote any songs in a lighter vein; if so, it would have been nice to have a bit of contrast. Incidentally, it seems that Download purchasers can access two additional tracks: Widmung, Op. 20 No. 1 by Müller-Hermann and Einem Vorangegangenen by Schweikert. I’m not clear why these aren’t also on the CD; since the songs play for less than six minutes in total, there would have been ample room.

The songs of Richard Strauss and Mahler need no introduction, of course. Kitty Whately has selected five excellent examples of Strauss’s Lieder. Befreit is an ardent song; the music is deeply-felt, as is the present performance. Allerseelen is one of my favourites among the composer’s Lieder output and I’m delighted with the performance that Whately and Middleton offer here. Kitty Whately is very communicative in the rapturous Rückleben. Arguably, both performers save their best for Morgen! Joseph Middleton achieves ideal poise in the long introduction and when Kitty Whately joins him she spins the extended vocal lines beautifully. Playing and singing are expertly controlled – though one is unaware of the technical aspects; we can focus on the musical poetry instead. This is a moving performance.

Revealingly, Kitty Whately comments in the booklet that although Kindertotenlieder has always touched her very deeply, her response to these songs by Mahler has become even more intense since she became a mother. I hadn’t read those comments when I first listened but my notes include the comment “she engages with the songs passionately”. She is, for example, highly expressive in her delivery of the first song, ‘Nun will die Sonn’ so hell aufgeh’n!’ To be honest, though, all five songs are sung with great expression and it’s almost invidious to single out one. That said, there are two reasons why specific mention must be made of the performance of ‘In diesem Wetter!’ Firstly, Kitty Whately sings it marvellously. In the first four stanzas of Rückert’s poem she really conveys the increasing desperation of the mother whose children have gone missing in the storm,. Then in the final stanza it is impossible not to be touched by her resigned acceptance. The second reason for singling out this song is the contribution of Joseph Middleton. I think it’s always a challenge for a pianist to compensate – if I may use that term – for the absence of an orchestra in these songs. Middleton achieves that: at no time did I miss the orchestra; instead, I relished the intimate scale of singer and piano. Nowhere is Middleton more successful than in the concluding song. We hear great turbulence in the piano in the early part of the piece. Subsequently, Middleton judges the mood of the final stanza just as keenly as does Ms Whately and then he delivers the poetic piano postlude with great sensitivity. I admired this account of Kindertotenlieder very much.

This is a very rewarding album. The programme has been well designed by the artists and they execute it marvellously. I enjoyed Kitty Whately’s expressive and communicative singing very much indeed and in Joseph Middleton she has a musical partner with whom she is clearly ‘as one’; theirs is a perceptive partnership. The Strauss and Mahler items are very successful but, for me, the great dividend is the opportunity to discover and appreciate the songs of Joanna Müller-Hermann and Margarete Schweikert. Both are composers of genuine worth and it is distressing that their music has remained in the shadows for so many years. I hope very much that the fine advocacy of Kitty Whately and Joseph Middleton will win the songs new admirers and will prompt a revival of interest in these two composers; it is nothing less than they deserve. It’s appropriate that the album has been given the title ‘Befreit’ (Released) because the recordings of these ten songs do indeed release their respective composers from unwarranted neglect.

In the booklet, Kitty Whately acknowledges the assistance of quite a number of people who have helped her to bring to fruition her discovery of these two composers. It is evident from the list that this has been a painstaking project; it has been a worthwhile one.

It remains only to say that the production values of this release are high. Producer/engineer Jonathan Cooper has recorded the artists very successfully, achieving a very good balance between singer and piano; that’s something which is very important in rich, romantic music such as this. The documentation is first-class; the essays by Paul Griffiths and Kitty Whately are excellent.

John Quinn

Help us financially by purchasing from

Contents

Joanna Müller-Hermann (1878-1941)

Wie eine Vollmondnacht, Op. 20 No. 4 (1920s?)

Der letzte abend, Op. 2 No. 4 (c 1907)

Richard Strauss (1864-1949)

Befreit, Op. 39, TrV 189 No. 4 (1898)

Allerseelen, Op. 10, TrV 141 No. 8 (1885)

Margarete Schweikert (1887-1957)

Wolke I (1935?)

Totenhausen (1935)

Zusammen sterben (date unknown)

Richard Strauss

Auf ein Kind, Op. 47,TrV 200 No.1(1900)

Rückleben, Op. 47, TrV 200 No. 3(1900)

Morgen! Op. 27, TrV 170 No. 4 (1894)

Joanna Müller-Hermann

Die Stille Stadt, Op. 4 No. 1 (1904)

Herbst, Op. 20 No. 2 (1920s?)

In Memoriam, Op. 28 No. 5 (1940?)

Margarete Schweikert

Unser Haus (1912?)

Die Entschlafenen (1923)

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911)

Kindertotenlieder (1901-04)