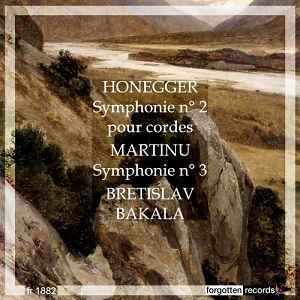

Arthur Honegger (1892-1955)

Symphony No.2 for strings and trumpet, H.153 (1941)

Bohuslav Martinů (1890-1959)

Symphony No.3, H.299 (1944)

Brno Philharmonic Orchestra/Břetislav Bakala

rec. 1956, Warsaw

Forgotten Records FR1882 [53]

In 1956 Břetislav Bakala (born 1897) was appointed the first conductor of the newly established Brno (State) Philharmonic, which was formed of two existing orchestras, the city’s Radio Orchestra and the Brno Region Symphony. His position was short lived as he died two years later in 1958 at the early age of 61. Bakala should have made many more recordings than he did. A composition pupil of Janáček in Brno, and a pretty much permanent resident of the city, it was probably the relative geographical remoteness, as well as the city’s independence, from Prague that meant that his discography is so slender for so important an artist. As collectors know, his Janáček recordings are spearheaded by the Glagolitic Mass, Taras Bulba and the Sinfonietta but include other, smaller Janáček works (some of this body of recordings, it’s true, were made with the Czech Philharmonic), as well as other major Czech pieces like Novák’s The Spectre’s Bride. But for his death the preceding year, it seems inconceivable that Bakala, for decades the leading Janáček conductor, would not have been offered the 1959 recording of Kát’a Kabanová, and the international exposure it generated. Instead, it was offered to Jaroslav Krombholc and it’s seldom been out of the catalogue since.

Shortly after his appointment, Bakala and the orchestra travelled to the Warsaw International Festival of Contemporary Music which took place between 10 and 21 October 1956. I assume the orchestra took both these works to the festival and recorded them at the same time for Muza (in full, Polskie Nagrania Muza), though I’ve not been able to verify that. The Honegger was released on L0166 and the Martinů on L0150, the first LP of a work that had first been recorded on 78s by Karel Šejna in 1949. The Honegger had first been recorded in October 1942 and March 1944 in an interrupted recording by the Paris Conservatory Orchestra conducted by Charles Munch. So, these two symphonies shared many correspondences, not simply the date of composition, but the obvious matter of the war, a sense of melancholy that elides into despair, and an ultimate belief in a transfiguring triumph. They are also both three movement symphonies that share a similar length and conception.

No performance of the Honegger has ever matched the first of Munch’s three commercial recordings for sheer visceral intensity. He blazes through the central slow movement in a mere seven minutes – in his celebrated recording von Karajan takes well over nine – and even Serge Baudo has to cede something to Munch’s on-the-spot intensity of vision. Bakala shares Munch’s tempo in the opening movement which is finely sculpted and Bakala’s transition from the Moderato to the Allegro is splendidly accomplished. Terse, taut and tensile but with a metrically flexible melancholia, Bakala steers the Brno orchestra through the opening with rhythmically pointed excellence. Bakala takes a mid-point view of the Adagio, that’s to say mid-way between Karajan and Munch, but his finale sounds a touch slack. He is inclined to heed the qualifying ‘non troppo’ somewhat at the expense of ‘Vivace’. It’s true that this makes the chorale theme emerge with more nobility, at this slightly relaxed tempo, but along the way the sense of galvanizing hopefulness that Munch generates is lost. The Brno orchestra plays well though obviously not with the finesse and personal stamp of their colleagues in Prague.

Incidentally Forgotten Records prints the date of the Honegger as 1937 but this was the date Paul Sacher commissioned it. It was completed in 1941 and premiered the following year.

When it comes to Martinů’s Third, replace the name ‘Munch’ with that of ‘Ančerl’ and you have a similar point of comparison, though in this case Ančerl’s live performance was given in the 1960s. It shares with Munch’s Honegger a lithe, intense and fleet central movement faster than any other I’ve encountered, though the recording quality isn’t up to much (it’s on Multisonic). Bakala takes a perfect tempo in the first movement establishing its unease immediately, its propulsion always accompanied by a terse drive. The searing drama of the Largo fuses with paragraphs of elysian innocence but always framed within a strong narrative pulse. Winds are forward, transitions, once again, work very well. The finale marries expressive chamber intimacy with abrupt eruptive intensity. Bakala’s great quality here is his skill in marrying disparate elements together, as he leads the music to a sort-of optimistic ending. But for the finale, the performance presages those of Bělohlávek and the BBC Symphony, and also, somewhat more improbably, Cornelius Mester in his recent complete symphonic cycle. Ančerl, meanwhile, shares an interpretative alignment with Bryden Thomson in his set of the symphonies.

There are no notes with this disc, as is usual for the label.

I hadn’t come across these performances before. They’ve been finely transferred and have very quiet surfaces, though as you’d expect from their vintage, there are moments of orchestral congestion. Together they show that Bakala and his newly established orchestra were perfectly capable of promoting new and important symphonic music to an international audience, whilst demonstrating first class corporate strengths.

Jonathan Woolf

| Availability |  |