Franz Schubert (1797-1828)

Schwanengesang (1828)

Einsamkeit (1818)

Ian Bostridge (tenor), Lars Vogt (piano)

rec. 2021

PENTATONE PTC5186786 [69]

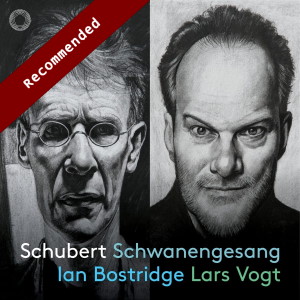

As the singer, Ian Bostridge will probably be the biggest draw to potential purchasers of this disc, not least because it is the third part in his newly recorded trilogy of Schubert song cycles for Pentatone. That’s misleading, however: this disc is very much a partnership of equals, something made evident by the drawings on the cover, and in many ways it’s Lars Vogt’s contribution at the keyboard that really makes the disc distinctive.

Indeed, the partnership aspect of this disc becomes all the more poignant in the light of Vogt’s untimely death in September 2022 at the age of only 51. Having lost Vogt so prematurely it’s easy to drift into hyperbole, but it’s not an exaggeration to say that we have here two artists performing at the very peak of their form. Indeed, it’s Vogt’s piano that really takes centre stage in Einsamkeit, the disc’s “filler.” It’s a marvellous thing, this piece; not quite a song cycle, but seemingly more substantial than one mere song. It’s a study of contrasts in human nature and experience, and the piano seems to be the prime mover throughout. It tolls bells of solemnity in the first movement, asserting upward leaps of longing as the call of the world reasserts itself, then bustles through the busy city before solitude calls. Each stanza/section matches one mood against another, and Vogt is terrific in each, investing each phrase with drama and passion that almost turns it into a miniature tone poem. Bostridge’s word-painting is every bit as good, and Einsamkeit serves as an excellent companion piece to the disc’s main event.

Bostridge has recorded all three Schubert song cycles at least once before but, as with his Die Schöne Müllerin in this series, his interpretation seems to deepen and become richer with the passing of time. Bostridge’s gift for the inflection of language is wonderfully obvious in every song. He seems to turn every phrase around in his mouth before it leaves his voice so that every song is redolent with meaning. This is decidedly a Schwanengesang from a singing actor.

That doubles its power: both musically and linguistically every passage is full of feeling. He even puts the limitations of his voice to good use: he struggles to reach the lower passages of Kriegers Ahnung, but these add to the soldier’s sense of helplessness and foreboding. Aside from that, however, the cycle sits very well for him, and the songs’ combination of beauty and loss suits the colour of the voice very well. In In der Ferne, for example, the plangent quality of Bostridge’s voice fits very well the wanderer who cannot find peace, and just listen to the way he accentuates words like “Schmerze” and “Herze.”

Vogt’s piano line is every bit as good, however. The brook in Liebesbotschaft positively sparkles under Vogt’s fingers, something that’s indicative of the detail that he lavishes on every song, every stanza. Frühlingssehnsucht bristles with hopeful expectation, and there is a lovely Volkisch element to the bouncy accompaniment of many of the traveling songs. The piano does most of the heavy lifting in Atlas, conveying a world of agony in its roiling chords, and the ripple of the oars in Die Stadt is utterly chilling.

These two artists are easy to praise separately, but they come together to produce something incomparably richer than the two parts. You’ll go a long way to hear a more thoughtfully interpreted Ständchen, for example. This performance marries beautifully the piano’s undulating, wave-like line against Bostridge’s beautifully utilised tenor, and both turn to desperation in the final stanza as the lover yearns for the return of the beloved. Likewise, the bouncy piano line of Abschied matches Bostridge’s vocal line in the upbeat farewell to the town, but neither voice nor piano can hide the regret that lies behind the traveller’s departure: you sense it long before the final stanza’s subtle change of colour. Piano and voice sound utterly in tandem during the desperate sadness of Am Meer. Perhaps the climax of the cycle, however, is Der Doppelgänger, which begins in barely a whisper in the voice and rises to a frenzy of despair, while all the time the piano sounds like tolling funeral bells. Bostridge even colours Der Taubenpost with a tinge of bitterness, as though the pigeon’s faithfulness is as deceptive as the other images of love we encounter in the cycle. The song always serves as a rather odd way to end the cycle: here Bostridge seems to argue a convincing case for it. High praise!

Bostridge’s earlier Schwanengesang with Antonio Pappano is terrific, and I wouldn’t want to be without it. It’s the poignancy of Lars Vogt’s contribution that makes this one special, though. The expressivity of both voice and piano bring the listener deeper into both the music and the words, and help to provide an experience that is deep, enriching, and often very moving.

My only gripe is, again, with Pentatone’s packaging. Sung texts are provided, and we’re lucky that both the translations and the essay comes from Lieder authority Richard Stokes. Yet Pentatone insist on gluing the booklet into the CD case, making it cumbersome and unnecessary unwieldy to handle. Is it unreasonable of me to find this maddening?

Simon Thompson

Help us financially by purchasing from