Opera – The Autobiography of the Western World

by Simon Banks

Published 2022

Hardback, 326 pages

Matador Publishing

According to his short bio on his website, Simon Banks taught art history at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland and had a career in qualifications management with Cambridge Assessment. Since 2019 his publications include articles in Opera magazine and programme notes for Wexford Festival Opera in Ireland. He should not be confused with another Simon Banks who is a key-note speaker and author of design thinking books.

Opera – The Autobiography of the Western World seems to be Simon Banks’s first book. His website is entirely geared for it, with little other information. However, it is worth a visit to explore the book, read extracts, see some reviews and learn something about the author before deciding whether to purchase it.

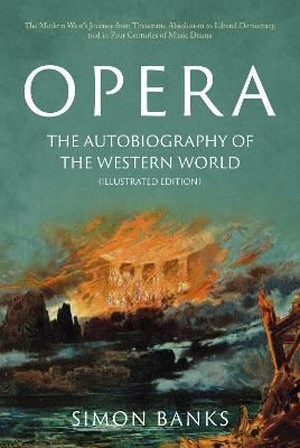

The first thing one notices about this book is that it is physically beautiful. The hardback comes in a dark charcoal binding with golden letters, inside a glorious, vibrant jacket which reproduces a painting by German artist Max Brückner (1836-1919), entitled The Twilight of the Gods. It depicts the destruction of Valhalla and is based on his own stage sets at Bayreuth in 1894. Open the book and you will be immediately struck by the excellent quality of the paper and by a long descriptive subtitle: The modern West’s journey from theocratic absolutism to liberal democracy, told in four centuries of music drama. Begin paging through it at leisure, before reading, and you will be presented with a wealth of gorgeous images – reproductions of paintings, drawings, portraits, lithograph prints, sketches for settings and costumes, programme covers and photographs – all mostly in colour and some also in black and white. It is almost like one of those splendid picture books made to handsomely decorate coffee tables that people page through carefully from time to time, admiring the beauty of their images and the artistic skill in creating the physical book.

The title Opera – The Autobiography of the Western World shows aspiration. To include “the autobiography” hints not only at an interesting idea but also at a rather ambitious project. Returning to the descriptive subtitle (mentioned in the previous paragraph) one is able to confirm that ambition. In his personal note at the beginning of the book, Banks states that after his father’s death he found time to start his dream project, i.e. to tell the story of Europe as chronicled in opera. That the story of the continent is documented in opera is nothing new but to capture and record into one single book the history of the western world through the operatic works of various composers is not only an obvious labour of love but also a challenging, rather grandiose endeavour. After reading it, I must say I appreciate the arduous work and research involved in producing this book, found it engaging but I am not absolutely certain the author achieved his objective. It is a personal opinion. I love history, enjoy reading the detail and always want to learn and discover more. This book did not offer me that but it may well do so for a reader less demanding on the subject than I am.

It is extremely difficult to abridge the history of the western world, whether through opera or otherwise, in one single volume with 326 pages, some of which are illustrations. I must say that the author did an outstanding job bearing in mind the difficulty and sheer size of the project. Unsurprisingly in a work of this nature, there is little detail be it about the story of the western world, the operas or the composers mentioned. Inevitably, perhaps due to the need to curtail and compress, the explanations or the narrative are, to me personally, far too brief and I was sometimes left with a slight feeling that something was missing. I suppose it indeed is something missing or we would have several volumes. This I think leads to occasional historical inaccuracies. The one that screamed at me most obviously (perhaps because it is related to a subject I studied) is on page 79, chapter 13, entitled The End of the Norse Gods. The chapter begins by setting the tone and I quote:

‘From 1805 onwards, opera explored the recent centuries of European history. In tragedy after tragedy, revolutionary-romantic operas gave a hostile account of modern Europe’s inherited structures of church and state, and highlighted the negative impacts these institutions had had on the lives of the people who lived under them.’ So far so good but then comes my problem, ‘Donizetti told stories of corrupt power in Spain (Dom Sebastien)…’ While it is of course true that Donizetti wrote the opera Dom Sebastien, I don’t think it’s about corrupt power in Spain at all. First of all Dom Sebastien was a Portuguese king. Second the topic is the dynastic crisis he caused in the country and its impacts on the people of Portugal. Sebastien (or Sebastião, as his name is in Portuguese) was little more than a teenager when he inherited the throne. Misguidedly he decided to leave to fight the Moors in the North of Africa where he died in battle. His body was never found. Unmarried and without heirs Sebastien simply abandoned the country to its fate. Philip II was king of Spain at the time. His mother was a Portuguese Princess, Isabel of Portugal. His first wife was also Portuguese (Princess Maria Manuela of Portugal). Through these lines Philip II had a thin claim to the throne of Portugal but, in 1580, as Sebastien was dead and had no children and his closest relatives were also dead, Philip’s right was confirmed and he became Philip I of Portugal, II of Spain. Portugal lost its independence, which it only regained in 1640, after the rebellion against the Spanish rule on 1st December of that year. The Duke of Braganza then ascended the throne of Portugal as King John IV (Dom João IV) but the story didn’t end there. The so-called Restauration War between Portugal and Spain was to last another 20 years. Only then did the Spanish monarchs finally give in and recognise the new dynasty of Braganza as the legitimate heirs to the Portuguese throne. In the whole context of Banks’s book this is not really relevant, however, it can induce people to believe information that is incorrect. Of course the plot of Donizetti’s opera Dom Sebastien is historically a complete fiction though many of the characters were real people. Why I’ve pointed out the small inaccuracy is because if one approaches the opera with the correct knowledge, it really is a work that effectively demonstrates the often adverse impact monarchs and clergy had on the lives of the ‘little’ people, as Banks summarises in the opening paragraph of chapter 13.

In spite of what I stated above, I very much liked Opera – The Autobiography of the Western World and found considerable pleasure in reading it. There is much to enjoy. The book is well organised in chapters that refer to topics about the history of the western world in a logical chronological manner. Each starts with a table that briefly lists the history – containing dates, topic, name of composer(s) and work(s) (opera or oratorio). Then we have the narrative about the history, the works and the composer and what they relate to in terms of the beliefs and politics of a particular period. This actually means that one doesn’t need to read the book in the order in which it was written. If you are interested in reading about particular operas by certain composers there is a very useful index at the end of the book where the composers are listed in alphabetical order in the first column, then their operas/oratorios in the second and chapters where they are included in the third. Simon Banks is a good writer. The narrative flows seamlessly; the use of language is excellent – erudite without being pompous, fluent and eloquent. Opera – The Autobiography of the Western World is an excellent book to use as source for quick references, be these historical or about composers and their works.

Fascinating and rather satisfying were for me the Introduction, the Personal Note and the Prologue to this book. They not only set the scene and explain how the book works but also provide an insight into the mind of the author, which is always an engaging prospect.

In order to reflect the worldviews of Monteverdi, Handel and Rossini – as Banks explains in a brief note at the start of Chapter One – he uses the chronology of the Timechart History of the World, first published in the 19th century and which takes an entirely biblical view of ancient history. It is clearly marked with THW but while I understand why Banks did this, I found it distracting and unnecessary to grasp the worldviews of a certain period.

The edition I reviewed of this book is the one in hardback format, which as I said, is rather beautiful. Recommended retail price is £40.00 but it is available on Amazon for £27.89. There you can also find it in paperback format for £22.75 and as Kindle e-book for only £9.99. I have no idea how the paperback or the e-book fare compared to the hardback, as I haven’t seen them, but I doubt the images (if they are included) will have the same quality and beauty. So, if you are interested in purchasing this book, I would say that you are probably better served with the hardcover edition.

In all, Opera – The Autobiography of the Western World, is a captivating, admirable work. It is no doubt ambitious and to call it the autobiography of the Western World is a daring claim. I think historians will possibly find it incomplete; Opera lovers will almost certainly savour it and relish some of its chapters. I found it enjoyable and engaging if not fulfilling.

Margarida Mota-Bull

Margarida writes more than just reviews, check it online: https://www.flowingprose.com/

Help us financially by purchasing from