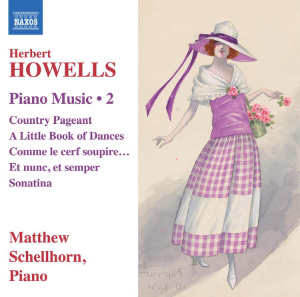

Herbert Howells (1892-1983)

Piano Music Volume 2

Matthew Schellhorn (piano)

rec. 2021, Menuhin Hall, Stoke D’Abernon, UK

NAXOS 8.571383 [69]

Volume 1 of this ongoing survey was released back in August 2020 and it proved to be something of a revelation (review). Pianist Matthew Schellhorn has returned to the same recording location with Ben Connellan engineering and Howells scholar Jonathan Clinch providing musicological support for this second disc. The good news is that it builds upon the very high standard of the earlier disc with the technical and musical aspects of this new release every bit as good as the first. Furthermore, Schellhorn and Clinch continue to unearth forgotten riches with fifteen of the seventeen works offered here being either world premiere recordings or premiere recordings of new editions.

Again following the overall plan of Volume 1, the music is offered – with the exception of the 1963 Comme le cerf soupire which opens the disc – in chronological order which proves to be both fascinating and rewarding in allowing the listener to trace the development of Howells’ compositional voice. At 6:20 Comme le cerf soupire [the title is taken from an old French Chanson] is the longest single musical span on the disc and although a later work the emotional landscape of pensive moods, lucid textures and emotional poise is a consistent feature of nearly all these works. Another consistent feature across both albums is the ideal clarity technically and musically of Schellhorn’s playing. His control and expressive precision suit Howells’ aesthetic so well. The group of five works written between 1908-09 are remarkable not just because the composer was in his mid-teens but because of his keen ear for simple and effective textures and an avoidance of any kind of youthful bombast. For sure he would write far more sophisticated music but there is an intellectual maturity here that belies his youth. Jonathan Clinch in his insightful liner reminds the listener that Howells immersed himself in a wide range of piano repertoire all of which he committed to memory. At the same time the note books which contain these works include passages of Wordsworth, and song settings sitting alongside more formal composition exercises.

A common feature across all these works is a conscious use of what might be termed “diminutive” titles. Howells avoids evocative or high-Romantic titles instead opting for functional or even quite simplistic ones. This appears to be a common thread across all of Howells’ piano music from whatever period in his life so it is a clear and conscious creative choice. For sure this does in part reflect the directness and unaffected nature of the music but it would be quite wrong to mistake the apparent lack of complexity for something that was simplistic or lacking emotional weight. Interestingly, with the exception of the movements of the Sonatina – which appears as a fairly unique work in Howells’ keyboard output anyway – the group of early works; The Arab’s Song, To a Wild Flower, Romance, Melody, Legend are also the longest pieces. A strongly recurring feature of all the other works are their concision with only three on the entire disc longer than two minutes. But it strikes me that this brevity of scale and modesty of title is a clear creative choice.

Take The Chosen Tune [track 7 – 1:44] – the title alone has a rich resonance for Howells. Chosen Hill was where Howells and his very close friend Ivor Gurney would walk to appreciate the panoramic views of the surrounding Gloucestershire countryside. The village of Chosen (also known as Churchdown) was the home of his fiancée and this piano version was written for their wedding in August 1920. So this disarmingly beautiful miniature has layers of meaning which no performer can illuminate by their playing alone. But that said Schellhorn captures a wistful strength that is disarmingly beautiful. This is one of the few works to appear on another disc – Margaret Fingerhut’s thoughtful recital on Chandos where it is also beautifully played.

Howells was a close personal friend of Walter de la Mare and Jonathan Clinch points to a shared dedication to writing “poetic miniatures” for children. In part this might explain several of the child-like titles but what is certainly true is the success with which Howells was able to write music of a technical scale that was achievable by young musicians without compromising the musical or expressive ‘worth’ of the pieces. Allied to this friendship, in 1926 the photographer Herbert Lambert lent Howells a homemade clavichord inspired by Arnold Dolmetsch’s recreation of old instruments. This fortuitous confluence of events chimed with Howells’ interest in old English compositional traditions. As Clinch neatly puts it; “[the] expressive and miniature sound providing an antidote to what Howells referred to as ‘our crushingly noisy world’. This diminutive form of quiet intensity became an integral part of his musical language [where] Howells’ music represents a synthesis of de la Mare’s poetic miniatures of 20th Century childhood and the Elizabethan miniatures of Byrd and Tallis.”

“Quiet intensity” could be the neatest and most apt description of much of Howells’ music. So A Little Book of Dances written in 1928 comprises six very brief ‘old’ dances with No.3 Pavane the longest at just 2:10. But these are remarkably focussed yet gossamer slight works quite beautifully realised here by Schellhorn. They seem to represent a satellite work to the preceding year’s Lambert’s Clavichord Op.41 which is the wonderful set of twelve pieces that embody the first flood of Howells’ response to Herbert Lambert’s gift. Composer John McCabe made a wonderful disc of both Lambert’s Clavichord and the later/companion Howells’ Clavichord – the hope must be that at some point Schellhorn will turn his attention to these works. Alongside these Tudor recreations are the miniatures that seem to be a fusion of childhood and folksong. The brief [track 19 – 1:08] A Sailor Tune is a sea-shanty with a Grainger-esque heartiness if without the harmonic or textural complexity. Several of the works were literally written with young performers in mind but again the skill of composer and performer is to present the music with simplicity and directness.

The disc is completed by the pair of latest and most explicitly substantial works. The 1967 Et nunc, et simper [Is now, and ever shall be] is another minuet but here the dance form is subsumed into a freer, more harmonically questing work that again is notable for the same quiet intensity referenced earlier. At 15:24 for the combined three movements the 1971 Sonatina is by some distance the most substantial work on the disc with each movement alone longer than any other work on the disc with the exception of the opening Comme le cerf soupire. This is a work that has appeared in other Howells recitals – both Fingerhut and Jeremy Filsell on Guild include the work. While preparing for this new performance Schellhorn consulted the original manuscript as well as the work’s dedicatee and first performer Hilary Macnamara. According to Macnamara; “Herbert would still be changing it now if he could”. The result of this creative evolution are numerous variants from which Schellhorn has produced a new performing edition heard for the first time on this disc. Certainly the result is a work which – especially in the opening Vivo: inquieto – occupies a different more ambivalent emotional landscape. Admirers of Howells’ music will want to hear either Filsell or Fingerhut because they are both fine pianists clearly engaged with the music. Certainly Fingerhut takes the “inquieto”/restless/uneasy marking as the central motivation behind the music with the result more modernistic and questing than any of the other music here. Schellhorn is more playful – perhaps unsettled rather than restless. The central Quasi adagio; serioso ma teneramente was originally titled Sarabande on the manuscript but lost that title upon publication. This strikes me as one of Howells’ most sophisticated fusions of Tudor and Modernist aesthetics. There is a depth to this movement and indeed the whole work that makes the Sonatina title seem curiously, indeed inaptly, slight. Schellhorn performs this central movement with a great sense of rhythmic freedom – is it too fanciful to hear almost a lute fantasia in this approach? The cumulative value of this ongoing survey becomes clear when you realise that the Sonatina’s closing Agile, destro, sempre veloce is a reworking of the final movement Toccatina from the Petrus Suite included in volume 1. The common musical heritage is clear but they are distinctly different works. In reviewing that work I described the Toccatina as having “breezy good humour”. Here in the Sonatina the mood is somewhat more muscular but it is curious that Howells chose to revisit this music so soon in two such different works. Even in the weightier version of the Sonatina this is the slightest music in this work with the two preceding movements having greater significance. None the less, Schellhorn’s skill and insight ensures that this is an impressive conclusion to this wholly compelling and important recital.

From first to last this is a disc marked by skill, scholarship and care from all concerned. A genuinely significant addition to the catalogue of British 20th Century keyboard music in general and Howells’ oeuvre in particular.

Nick Barnard

Help us financially by purchasing from

Contents

Comme le cerf soupire… (1963)

The Arab’s Song (1908)

To a Wild Flower (1908)

Romance (1908)

Melody (1909)

Legend (1909)

The Chosen Tune (1920)

A Mersey Tune (1924)

Country Pageant (1928)

A Little Book of Dances (1928)

A Sailor Tune (1930)

3 Tunes (1932)

Minuet for Ursula (1935)

Promenade for Girls (1938)

Promenade for Boys (1938)

Et nunc, et semper (Quasi Menuetto) (1967)

Piano Sonatina (ed. M. Schellhorn) (1971)