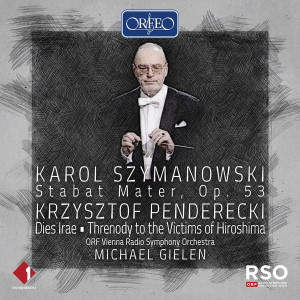

Karol Szymanowski (1882-1937)

Stabat Mater (1926)

Krzysztof Penderecki (1933-2020)

Dies Irae (1967)

Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima (1961)

Ewa Iżykowska (soprano), Elena Moşuc (soprano), Annette Markert (mezzo soprano), Zachos Terzakis (tenor), Anton Scharinger (tenor), Stephen Roberts (bass)

Chorus sine nomine, Wiener Konzertchor

ORF VIenna Radio Symphony Orchestra/Michael Gielen

rec. 1995-2000, Konzerthaus Wien

ORFEO C210311 [60]

Szymanowski’s Stabat Mater is, for me, his masterpiece. Reading Jens F. Laurson’s liner notes, I was pleased to discover that upon finishing the last movement Szymanowski reportedly exclaimed, ‘At last, I have written something really beautiful!’ Szymanowski has certainly written other very beautiful works, but there is something particularly enchanted – even miraculous – about the Stabat Mater. Its duality of Polish folk music and modernism, combined with an intensely personal interpretation of the text, resulted in one of the most colourful and passionate settings ever written.

I am usually ambivalent about Penderecki, whose Dies Irae and Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima follow the Stabat Mater, yet listening to this album my feelings were reversed; the performance of the Stabat Mater is underwhelming, while the Dies Irae is so powerful – one of the most frighteningly powerful recordings I’ve heard, and impossible to be ambivalent about.

In the Stabat Mater, Gielen focuses on the colour and neglects the passion. He lives up to his reputation for bringing out details, but to my ear he misunderstands the overall music. The mysterious orchestral counterpoint in the first movement is played matter-of-factly; its harmonic strangeness is emphasised at the expense of its lyricism. When the soprano comes in, the melody has little of the tender, other-worldly character that it ought to possess. We should have a sense of Mary, by the cross, and the tragic, perplexing majesty of this event and of life and death generally (after all, Szymanowski wrote the work partly as a response to the death of his niece and the grief of his sister). The last movement, which is the most beautiful culmination, is played in a similarly plain way. The music needs more of a Romantic flavour – more visceral and indulgent – than Gielen gives it.

Gielen has gone for an interpretation that is more dramatic than personal. This does result in some interesting ideas. For example, whereas I had previously thought of the fifth movement as magnificent, Gielen instead opted for strident – brutal, even. Stephen Roberts, baritone, is almost yelling at us, and when the orchestra and choir all come in at the end, with tremolo strings and timpani and tubular bells, it is like a great threatening march. Although the works were recorded five years apart, it is as if Gielen is anticipating the Dies Irae by Penderecki that will soon follow. It is a compelling way of playing the movement, and arguably congruent with the text, which ends “Lest I be consumed burned by flames / through you, O Virgin, may I be defended / on the day of judgement.”

This is neither the best nor the worst performance I’ve heard, yet neither is it mediocre; it is unbalanced but interesting. The singing is nonetheless very good, though sometimes feels constrained by the interpretation. I would recommend it to those wanting to hear a different take on the work. For those new to the work, try instead the recording by the Russian State Symphony Orchestra and Cappella, conducted by Valeri Polyansky (catalogue no. CHAN S9937). While Gielen captures the work’s strangeness, Polyansky and the Russian players and singers he conducts go deeper and capture the work’s mystery, its connection to the transcendent. Simon Rattle has also made a very fine recording (catalogue no. EMI CLASSICS 5145762), especially if you would prefer a more energetic interpretation.

The performance of Penderecki’s Dies Irae is much more impressive. The work was commissioned to mark the unveiling of the International Monument to the Victims of Fascism at the former Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp. The premiere of the Dies Irae took place there in 1967. This places it during the first phase of Penderecki’s compositional life, when his work was at its most intensely avant-garde. In the first movement, Lamentatio, we encounter a spare and apocalyptic soundworld. Out of it emerges a trembling, distressed solo soprano. The female choir then wails; the male choir chants darkly (unfortunately there is no translation of the text in the booklet, so I only had the vaguest idea what they are singing). The music is punctuated by brief explosions of timpani and cymbals and brass. Monotonal passages are used throughout to build the intensity.

The second movement, Apocalypsis, is a nightmare in sound. Whispering, chattering, shouting – it bears many similarities with Penderecki’s St Luke Passion, written the previous year. A siren cuts through the noise, then is heard alone in glissando descent, fading into the distance. There is brief silence, and the choir and orchestra erupt. More pauses, then wailing – the performance is captivatingly violent, with the wildest changes in dynamics. Afterwards, bells chime and chants layer on top of each other; the third and last movement, Apotheosis, has begun. It is by far the shortest movement, almost a last desperate cry. Indeed, it ends with a plea: ‘let us try to live’, followed by, finally, a softly-chanted ‘corpora parvulorum’, or children’s corpses. This is a piece of sustained horror, which might in other contexts be excessive; however, it is hard to think of any other response to the Nazi death camps. I found moments genuinely frightening, and I did not want to listen to it twice.

Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima makes less of an impact, though it is conducted and performed equally superbly. Its nine minutes of extreme, yet highly expressive, orchestral writing remains compelling, but it possibly suffers from coming after a work such as the Dies Irae. I think it may have to do with the absence of the human voice. Threnody’s tone clusters, quarter tones, string slaps, and various other extended techniques, can never be as horrible, as desperate, as imploring as sorrowful voices.

In Dies Irae, Gielen unleashes an emotional strength that he never really found in the Stabat Mater – you are unlikely to find a more impressive recording. The latter, despite being the far more luscious work, comes across as relatively cold and distant. Nevertheless, Gielen’s interpretation brings out some aspects that will interest those familiar with the work.

Steven Watson

Help us financially by purchasing through