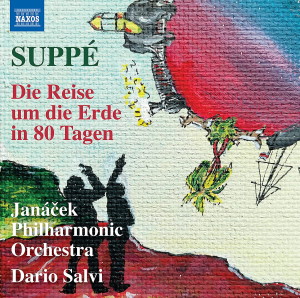

Franz von Suppé (1819-1895)

Die Reise um die Erde in 80 Tagen (1874) – stage music (version without narration)

Janáček Philharmonic Orchestra/Dario Salvi

rec. 2021, House of Culture, Ostrava, Czechia

First recording

NAXOS 8.574396 [51]

Anyone associating Jules Verne’s 1872 novel Le tour du monde en quatre-vingts jours with music will most likely be thinking of the 1956 Hollywood movie Around the world in 80 days. That Oscar-winning film’s title music was quickly transformed into a song that became a regular fixture on such UK radio shows of the time as Housewives’ choice and Two-way family favourites. One hopes, however, that there weren’t too many BBC listeners relying on it to plan an ambitious trip around the globe, for the only destinations that were actually mentioned in its lyrics turned out to be the somewhat unambitious selection of County Down, New York, Gay Paree – spelling was never a strongpoint in Hollywood – and London Town.

Encompassing a journey of far wider geographical scope, Verne’s original novel had been predicated upon the massive expansion of rail and steamship networks across the globe that characterised the mid- and late 19th century. Indeed, it is neatly symbolic that the year 1872 witnessed not only the publication of Le tour du monde en quatre-vingts jours but also the foundation of the travel agency Thomas Cook & Son. Verne’s novel consequently enjoyed an immediate success among affluent readers eager to pack their bags and explore the wider world. Incidentally, even music proved susceptible to the contemporary air of wanderlust, for the growing interest in unfamiliar locales inspired many composers to incorporate ethnic – or, rather more often, pseudo-ethnic – influences into their scores. Thus, the Russian “Mighty Handful” not only collected folk material from central Asia but recycled some of it into their own compositions, while Debussy’s fascination with the Javanese gamelan music that he first encountered at the Exposition Universelle de Paris in 1889 became an important influence on the way in which his own musical style was to develop.

This new Naxos release offers us what is probably the first music composed in response to Verne’s novel – Die Reise um die Erde in 80 Tagen. It was written by Franz von Suppé within a few years of the book’s publication and was heard for the first time in March 1875 by the patrons of Vienna’s Carltheatre.

The Carltheatre tended to specialise in operettas and had frequently staged the first performances of von Suppé’s works. A few, notably Die schöne Galathée (“The beautiful Galathée”) and Leichte Kavallerie (“Light cavalry”), remain familiar names today, if only thanks to their jauntily memorable overtures. Rather more, including Die Freigeister (“The free spirits”), Die Frau Meisterin (“The lady mistress”) and Cannebas, are now pretty well unknown to all except diehard operetta aficionados. One that might still, I suspect, raise a smile is Lohengelb, oder die Jungfrau von Dragant (“Blaze Yellow, or the virgin of Dragant”), a parody of Lohengrin in which the re-named villainess Gertrud joins the heroine Elsa in a yodelling duet, while the knightly hero is drawn onto the stage not by a swan but by a sheep. Thankfully, as a couple of recordings of live performances confirm, von Suppé made no attempt to imitate Wagner’s musical style but kept very much to his own tried and tested formula.

On this particular occasion, however, it wasn’t an operetta that was on the Carltheatre’s programme. Instead, von Suppé had written music to accompany a new Spektakelstück (“spectacle play”). That, as its name suggests, was not a highbrow form of entertainment. On the contrary, it was one that was often quite specifically designed to appeal to less well educated audiences akin to Shakespeare’s groundlings. Indeed, in the case of Die Reise, its authors had taken care to employ the services of a narrator, just to make sure that the audience didn’t lose track of precisely which part of the world was being depicted at any one time. And while it’s true that this particular Spektakelstück featured a cast of actors, their job was less, I suspect, to act than to react, for the show’s most important elements were strictly visual, with plenty of energetically-presented, colourful and crowd-pleasing effects designed to generate what we nowadays call “the wow factor”.

As heard on this new disc, Die Reise’s opening prelude is followed by 15 separate tableaux, each depicting an incident in Verne’s picaresque story and each accompanied by von Suppé’s music. Those individual episodes are generally short. The most substantial of them turns out to be Tableau 4: Auf dem Scheiterhaufen (“At the funeral pyre”) which clocks in at just over seven minutes, while the most concise, at just 53 seconds, is Tableau 14: Ein freiwilliger Verbrecher (“A voluntary criminal”). The average length of a single tableau is a little over three minutes. Given the score’s fragmented nature, the booklet notes, penned by both the conductor Dario Salvi and musicologist Robert Ignatius Letellier, are especially useful in providing clear and useful guidance to what’s going on at any particular point in time.

As my previous review of the incidental music to the Leonard Wohlmuth’s 1854 play Mozart indicates, this was not the only occasion on which von Suppé produced an episodic score of this nature. As a jobbing composer who needed to earn an income, he was clearly more than happy to turn his hand to whatever commercial opportunity came along. No doubt he considered his music for a commission like Die Reise as very much of a specific time and place and essentially ephemeral. While he might possibly have conceived of future revivals of the Spektakelstück and his accompanying score, he would no doubt have been astounded to learn that it would reappear before the public after a gap of almost 150 years in a form designed to be listened to in a domestic environment and in the complete absence of any eye-popping on-stage action.

The absence the visual element does, it’s true, create something of a problem. After all, the Carltheatre audience had paid its money primarily to see, rather than to listen to, something. No doubt the theatregoers also appreciated, if only subliminally, the music that enhanced the atmosphere and emotions generated by the on-stage action – but that was not their main focus and von Suppé would no doubt have been well aware that he had been commissioned to write a score to support that action rather than to dominate or overpower it. As a result of that entirely understandable consideration, his Die Reise music as heard in the abstract sometimes struggles to make much of an independent or distinctive impression – and that’s especially the case when it’s as fragmentary as it often is here.

The score, nevertheless, has a great deal going for it – even if some of the pleasure comes from its frequent moments of unintended incongruity. As far as I’m aware, von Suppé had never actually visited Egypt, India, Borneo or California, so it is hardly surprising that, like many other European composers of the time, he had a rather indistinct notion of what the indigenous music of those places sounded like. As a result, the colour that he adds to his orchestration at various points in Die Reise is sometimes somewhat clichéd and occasionally quite bizarrely out of place. An episode (Tableau 2) taking place at the Suez Canal, for instance, is supported by music that your mind’s eye might be more likely to associate with Native Americans on the warpath, while a subsequent burst of martial music (Tableau 2b) sounds more like something accompanying a parade-ground exercise by an Austro-Hungarian cavalry regiment. Occasionally, too, you’d swear that von Suppé is following in the footsteps of another composer – though in fact it turns out to be the reverse. The jaunty central section Tableau 8, for instance, supposedly set in San Francisco, sounds, to my own ears, rather similar in style to the wedding dances at the rajah’s court in Ludwig Minkus’s La bayadère (1877). Similarly, the opening of the march in Tableau 7 (track 11, 2:03) immediately brings to mind yet another Housewives’ Choice favourite – the Procession of the sardar from Ippolitov-Ivanov’s 1894 Caucasian Sketches.

It is actually the more solemn and, indeed, sometimes quite profound, musical passages – which are also generally the longer and more substantial ones – that give Die Reise’s score some much needed ballast. Thus, the episodes set in India and Borneo (tableaux 7–11) emerge as the most successfully conceived and executed: a dramatic sequence, encompassing both grandiose funeral marches and eerie depictions of threatening jungles and serpent-filled caves, is strikingly orchestrated, with lowering, baleful trombones and an ominously threatening tam-tam establishing and then developing a dark air of despair and menace. After that impressive achievement, the subsequent, more up-tempo episodes set in North America are a far less interesting instance of mere style over real substance. In particular, the sequence proves over-reliant on a gold-miners’ march that’s repeated so often that it quickly makes one wish that those particular gentlemen had spent rather more of their time underground.

Overall and in spite of its inherent structural problems, Die Reise offers an enjoyable 51 minutes’ worth of listening. While I doubt that it will become one of the more regular CDs on my home player, this is a valuable release that increases our knowledge of von Suppe’s considerable output. The Scottish-Italian conductor Dario Salvi has a particular interest in reviving long-neglected repertoire from the mid-19th century and has done so on this occasion with his usual commitment and skill. As for the Janáček Philharmonic Orchestra, I have previously noted how idiomatically its members play when tackling unfamiliar material from that era and on this occasion they once again demonstrate considerable empathy with the material and expertise in its execution. The release benefits, moreover, from expertly engineered sound that uncovers plenty of orchestral detail. Unsurprisingly for a theatrical piece, you will also hear a few non-musical effects, including the shrill whistle of a transcontinental locomotive and a sudden gunshot from a six-shooter, that will, with the exercise of a little imagination, transport you far beyond the limits of County Down, New York, Gay Paree or even London Town.

Rob Maynard

Previous review: Rob Barnett (November 2022)

Help us financially by purchasing through